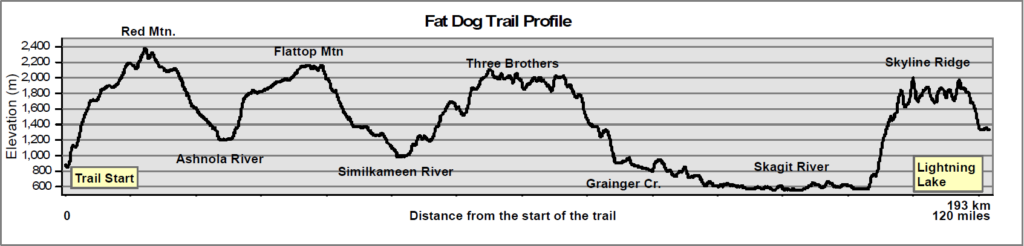

Just a few weeks ago, JOMH Field Editor Matt Thompson toed the line at of one of the toughest trail ultramarathons in North America: the Fat Dog 120. The 120 stands for 120 miles, the distance of the race. Yes you read that right, 120 MILES or 193 KM.

The average racer was expected to take between 30 and 40 hours to complete the event, a punishing course that traverses some of the roughest, steepest country in Southwestern BC. The total elevation gained over the entire course is just shy of what is required to summit Everest. From sea level.

It is a monster of an ultramarathon even by “ultra” standards.

When he decided to sign up for the event, Matt “volun-told” me I would be pacing him through the first night stage, meaning I would be running and hiking with him for a portion of the race. In this case, a 60km section that would take us 19 km up a technical single track trail to an exposed, alpine ridgeline, along this ridgeline for roughly 10 km and then descend over another 30 km to an aid station located along the only highway that passes through this remote part of the province.

So what the hell does this have to do with a First Lite jacket? Plenty.

Despite one the driest summers BC has seen in years, the weekend of the Fat Dog event brought storms, lightning, torrential rain, hail, and temperature fluctuations. The kind of weather that belonged on a Northern BC, YT or NWT sheep hunt, not what the racers had hoped to encounter on a mid-August endurance event in the Cascades.

Given the high mountain nature of the event and the remoteness between aid stations, the Fat Dog race organizers required all night-stage pacers to carry a variety of survival and inclement weather gear in the event racers ran into trouble in the middle of the night. I decided to pack my First Lite Boundary jacket as I figured I would get a chance to put it to the test for its waterproofness and breathability.

Matt and I left the aid station where I joined him at 9pm, after he’d already summited one mountain and covered 66km. The storms pounding the mountains had temporarily let up and the temperatures were in the low double digits (Celsius) so I was only wearing a long-sleeved merino base and a short-sleeved synthetic top on my upper body. We’d be climbing more than 4,300 feet or roughly 1,300 metres over the 19 km ascent to the next aid station so I knew we’d be generating some heat and opted to go without my waterproof shell to start. As we climbed however, the temps dropped quickly and the rain picked up again. Within 90 minutes of leaving the aid station, the Boundary jacket had to come out. We still had an estimated 2+ hours of climbing ahead of us and with roughly 20 pounds on my back between my water, food and mandatory survival gear the jacket was put to one hell of a thermoregulation test.

As some of you may know, a company can specify the waterproof and breathability ratings of their apparel in one of two ways: before or after printing a pattern on the fabric. With many modern textiles, the addition of a camo pattern to the material will alter the actual waterproofness and breathability in the field where it matters most. First Lite’s testing and ratings are all conducted after printing. The 20,000mm waterproof rating and 30,000 MVTR breathability ratings listed on the Boundary series is as field worthy as it gets.

I can personally vouch for the unbelievable breathability of the Boundary jacket. Over the remainder of our ascent I didn’t once feel clammy or saturated beneath the shell, and we were moving. This is a rare quality to find in a truly waterproof shell. Over the years I have spent a lot of time subjecting myself to the elements while engaged in some form of higher exertion activity, whether trail running, fast packing, snowshoeing, snowboarding or hunting. I have worn a lot of different high-end technical outerwear pieces from a lot of different manufacturers and I honestly have never been this impressed by a jacket. It was utterly bombproof to the elements while allowing my body heat to dissipate easily.

To give that additional context, the rain and wind intensified significantly as we climbed so I had the jacket fully zipped up, the hood up and a toque on by the time we reached the exposed ridgeline. I was not in any way allowing heat to escape through an open collar or the pit zips. This was a strict test of the jacket’s ability to breathe and dissipate internal heat while remaining fully protected from the rain and wind. It absolutely excelled.

When we reached the aid station around 12:30am, the temp had dipped down to low single digits (again Celsius), the wind was fiercely driving the rain into our faces and the clouds had sunk down to blanket the ridgeline we’d be traversing for the next 10km. We were literally enveloped in moisture and it was miserable. We still had another 8-9 hours of running and hiking ahead of us and another 5 hours before the sun rose. Matt and I took a short break at the aid station to fuel up with some warm soup, thaw out our hands and add a down layer beneath our waterproof jackets.

We left the aid station somewhat energized from the soup but dreading the next 10km section along the exposed ridgeline. The wind and rain were relentless, shaking the aid station tarps viciously against their guy lines as we left their protection. We put our heads down into the driving wind, rain and cloud moisture and soldiered on. Our visibility was less than 20 yards in every direction even with our headlamps set on their brightest settings and it took us nearly 3 hours to cover the measly 10km to the next aid station. A distance we can usually cover with ease in less than an hour. I can’t think of an experience in recent memory that would compare to the exposure we endured during that 3 hour slog. It was some of the wettest, windiest conditions I’ve ever encountered in the mountains. Under normal circumstances (aka not participating in an endurance event) we would have hunkered down for the night in the comfort of a tent but in this case that simply was not an option. We had ground to cover.

We eventually made it to the next aid station, nestled in some trees next to a small sub-alpine lake thankfully low enough to be protected from the wind. After a brief stop here we continued on our descent and it wasn’t until an hour later, after the sun had risen, that I finally decided to take off my Boundary.

All told I spent nearly 7 hours in that jacket, subjecting it to body heat, rain, wind, and significant temperature fluctuations. The Boundary excelled in each and every one of these tests and I cannot say this more emphatically: I have never worn a jacket that performed this flawlessly.

In just a couple of weeks I’ll be putting it through its paces on a Northern BC sheep hunt. For our sake I hope we have agreeable weather and clear skies so I don’t have to rely on what is now without question my go-to bombproof outerwear piece.

If you’re looking for a jacket that can truly do it all in the mountains, look no further.

Adam Janke

Editor in Chief