CHAPTER XIII

THE PELLY MOUNTAINS – 1905

July 22.—The next day was very hot, and after sifting out provisions for the trip and arranging a pack for Danger to carry, we spent the rest of the time about Nahanni House.

It consisted of nothing but a small log cabin used for a store; a small log warehouse, and another cabin which Lewis occupied. Jim Grew, who had constructed a small cabin across the river for head-quarters while trapping during the winter, had charge of the post during Lewis’s absence. He was over seventy-five years old and had served at different Hudson Bay trading posts all the way from Labrador to the Pacific. Though still active, he was too old for the hard work necessary for successful trapping; nevertheless he could not depart from his old life, and chose to die in the wilderness. His life was a mere existence, and three years later he was found dead in a cabin on the MacMillan. Dan McKinnon, his partner, was occupying Grew’s cabin. Van Bibber, a stalwart fellow brought up in the mountains of Kentucky, was there to meet his partner, Van Gorda, and with him was a young Indian boy from Liard Post. These two men had wintered in the vicinity of the Pelly Lakes, and had planned to return there.

July 23.—The whole month of July had been exceedingly dry and very hot. The next day was no exception. Many Indians had come to our camp for the purpose of seeing the horse, which aroused intense interest among them. That morning three appeared very early and watched us throw the pack on Danger. So great was their astonishment to see him walk off with a pack of two hundred pounds, that they followed us for three miles and showed us an Indian trail which led to the Lapie River, six miles above its mouth.

For the first five miles we traveled slowly, in a northward direction, crossing some heavily timbered ridges, often pausing to chop trees and brush, until we descended to a fairly level country sparsely timbered with spruces, poplars, and willows. After crossing seven miles through this, we came out upon a high bench rising directly from the Lapie. Through the valley of the river, which there emerges from a box cañon, I could see the interior Pelly ranges and the snowy peaks of the divide. As we were descending the bench to the river, the familiar chatter of the ground-squirrel greeted us. We slept near the brawling river, under a clear sky, and the noise of the current brought back many reminiscences of my trip up Coal Creek.

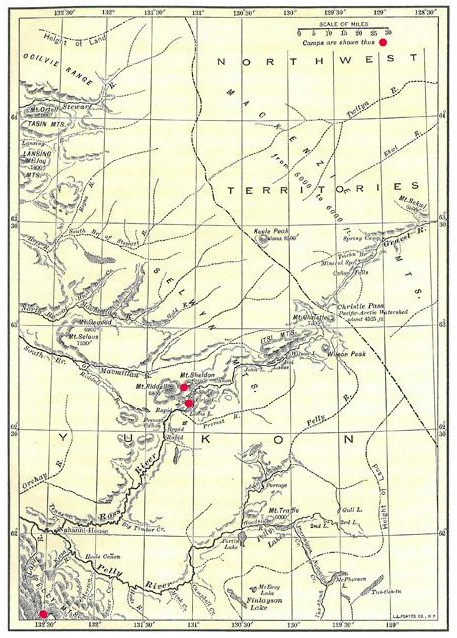

Map of Ross River, showing author’s hunting camps, including that in Pelly Mountains. Other hunting camps along the Pelly River are indicated in the map of Yukon Territory.

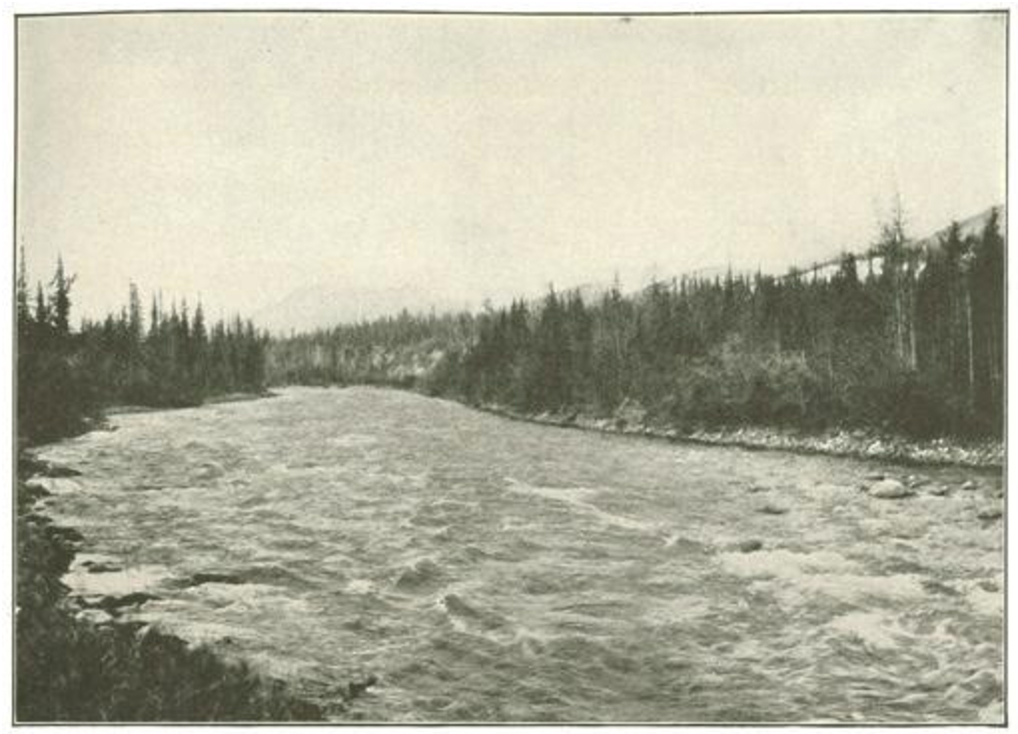

The Lapie River, so named by Dr. Dawson after one of the faithful Indian companions of Campbell, who first discovered it on his initial trip down the Pelly, enters the Pelly ten miles below the Ross. Its character is strictly similar to that of Coal Creek, but it carries a much larger volume of water—so large, in fact, that at the stage when I was there in both July and August, there was not a single fording place anywhere within fifty miles from its mouth. Through that distance it descends at the rate of thirty feet to the mile. From its source in the divide ranges, it flows in a north-east direction; its length is between eighty and a hundred miles; its width for the last forty miles, from seventy to a hundred feet, becoming narrower above.

July 24-26.—For the next three days the travelling was exactly like that on the upper reaches of Coal Creek, except that we were obliged to keep on the left bank, for even if a ford could have been found, it would not have been practicable to have taken a horse along the other side, because of continuous ridges sloping precipitously to the river. When we had travelled about twenty miles, the high, rough mountains completely engulfed us. The main divide was not more than twenty or thirty miles farther on in a straight line, and a fine large tributary, flowing from extremely rugged mountains more to the southwest—perfect sheep ranges—entered the Lapie a short distance north of the divide. I decided to ascend this branch to timber-line and make my camp. Timber-line was twelve miles distant, and nine hundred feet above that part of the Lapie. Moose tracks had been abundant along the bars of the river, nearly all going down stream, but their trails were not so well defined as those on Coal Creek. Rabbits, ground-squirrels, and red squirrels were plentiful, bear signs scarce, and bird life almost absent, except for golden eagles, Alaska jays, ravens, and goshawks. The weather was fair, and there were no mosquitoes, a most singular fact, which can only be accounted for by the extreme dryness of the season. I cannot forget the last tramp up the branch between lofty slopes topped by cliffs and jagged crest-lines, the magnificent mountains close by on both sides fairly hanging over us, as we climbed around canons through which the creek dashed in cascades over precipices and roared through deep gorges, until we reached the limit of the timber. There, where two forks join, each flowing from mountain-girdled basins, we made camp in the big spruces near the bank of the chattering stream.

Among all the spots in which I have ever camped, that was one of the most enchanting. The hard, dry ground was cushioned with spruce needles. Some of the spruces with big, gnarled trunks spread their dark-green foliage in canopy-tops, ornamented with thick clusters of hanging cones. Most of them shot up spires, their pointed tops giving the country that wild desolation so characteristic of the northern wilderness. Many inclined at sharp angles over the creek in graceful contrast, pleasantly breaking the austere straight lines of the forest, and producing a bowery effect above the splashing current as it raced in serpentine course down the valley.

Directly in front was the rolling basin of the South Fork, surrounded by a jumble of high peaks reared above snow-striped slopes, all the blending colors of their rocky surfaces in sharp contrast with the bright green of the upper reaches of the basin below, while numerous water-falls, pierced by the sun’s rays, as they dashed down the slopes, gleamed in different tints.

The mountains around the basins of the East Fork, perhaps smoother in outline, were equally high, and even richer in color.

Behind, almost overhanging the camp, reared up a long, high, savage range of limestone and granite; its slopes carved into canons and precipices; its crests serrated in rising and falling outlines, trimmed with radiating buttresses, spired peaks, and bands of snow, richer in contrasting colors than any of the other ranges observed in the Pelly Mountains.

But these inspiring views were near. Beyond, stretched a bewildering sea of summits, the more distant ones fading to the sight and suggesting the mysterious unknown.

Looking up the Lapie River, July 25.

The evening light glowed in the sky as we threw the load off the tired horse and made a fire. Luminous banks of burning crimson clouds hung over the summits of the South Fork; the sky in the east was cold and gray, while the light rays of the sun, then sunken below the nearer mountains, failed to reach the valley, then overspread with a deep purple hue, in sombre contrast to the brilliantly lighted mountains beyond. We did not attempt to erect the shelter that night, but slept beneath the spruces.

July 27.—Early in the morning I started off to obtain, if possible, a supply of meat for camp.

No description of the Pelly Mountains has ever been written. When Dr. Dawson spoke of them as dome-shaped granitic masses, smoother to the west, more serrated to the east, covered with a small herbaceous growth, slopes and peaks extremely uniform, shaped by normal processes of denudation, he was necessarily judging from the appearance of the outer range as observed from the Pelly River.

Once inside the outside range, they present an entirely different appearance, and it becomes clear that the denudation has not reached such an advanced stage.

The Pelly Mountains may be somewhat loosely defined as a group extending from the valley of the upper Liard in a north-west trend of crest outlines to the Orchay River, where they swing westward toward the Rose River. A gap of twenty miles of low ridges connects them with the Glenlyons, which may be considered as an interrupted continuation of the Pellys.

The series of parallel ranges extends through a width of from thirty to perhaps fifty miles, the peaks rising above sea-level from five to eight thousand feet.

They were formed by erosion from an uplifted plateau, and although a general trend can be detected, the ranges are so intersected by others, equally high, that it may be more proper to call them a complex, rather than a well-defined series.

In appearance they are more similar to the Ogilvie ranges than any other mountain group I have seen in the north. But in general they are higher, bolder, more irregular, and rougher; the valleys and canons are deeper, the crests hold more snow during the summer, the rivers draining them are larger in volume.

Timber-line, about 4,500 feet, is higher, and willow and dwarf-birch grow so much more densely on the lower slopes that all the mountains are more difficult to climb than those of the Ogilvies. Nature has carved the Pellys in more rugged outlines than those of the Ogilvies, and has given to them the same rich, contrasting colorations. It has carved even more beautiful basins among them, and filled them with the same kind of exquisite crystal lakes fed by melting snow. The same richly colored flora carpets the slopes.

I was about to climb among these wonderful mountains, and keeping close to the creek which headed in the east basin, where numerous graylings lay at the bottom of the pools, I saw, floating down among the riffles, two harlequin ducks, those exquisite creatures which adorn the dancing mountain creeks. The dense willow brush and dwarf-birches so impeded walking that it required an hour to go two and a half miles to the head of the basin. It was hot and sultry and a light haze hung about the crests. Again I was walking over emerald-green pastures in an amphitheatre of mountains, with ground-squirrels running about in all directions, while above me two golden eagles wheeled in flight.

The glories of the Pellys were spread out before me.

Beginning to climb a mountain on the west side of the basin, I was surprised to see a chipmunk picking up some kind of morsels among the rocks. Soon I was cheered by reaching a sheep-trail leading up the slope, and, following it, I at length reached the top, 6,900 feet altitude, according to my barometer.

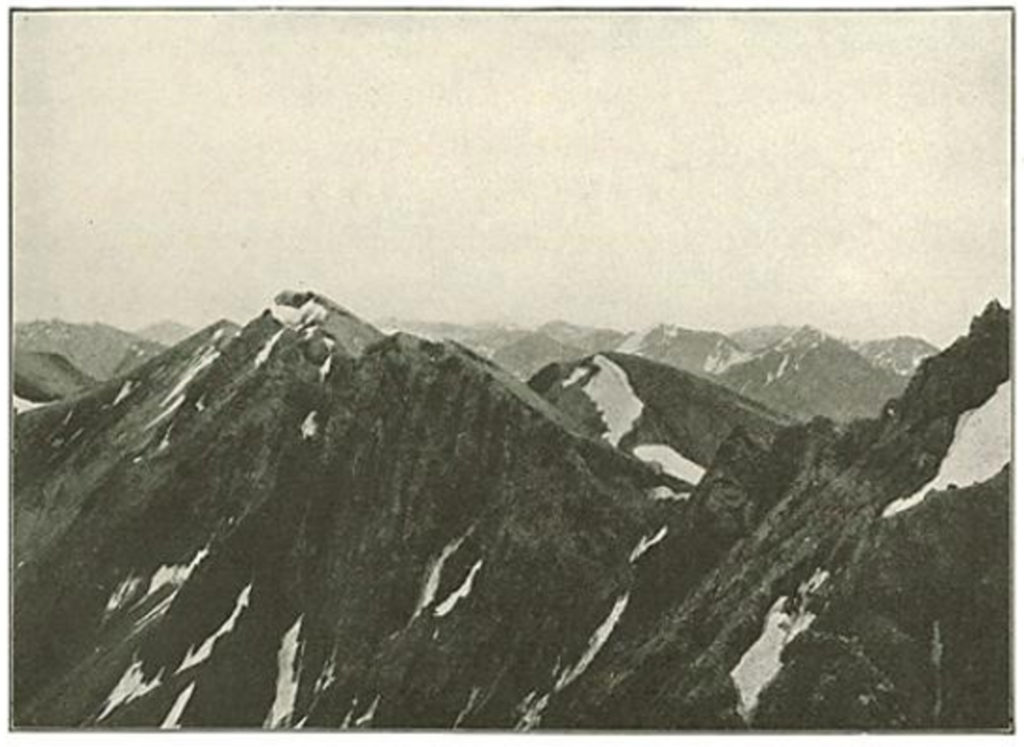

For the first time the glories of the Pellys were spread out before me—high, ragged ranges shooting up into the sky in all directions, the vision lost in a sea of peaks. No wind, not even a distant sound disturbed the silence.

The western face of the mountain fell in sheer cliffs for two thousand feet, the whole wall studded with castellated pillars of rock projecting upward from it; while below was an exquisite cliff-bound basin containing a shining lake.

A mile and a half across the basin was the crest of a mountain, below which was a cornice of snow covering about an acre and extending down a steep slope. As I turned my field-glasses along the crest, a grizzly bear standing on the sky-line just above the snow, came into view. The bear, high on the mountain-crest, outlined against the sky, presented a wonderful picture of wild life in a stupendous landscape.

It soon jumped over into the snow, walked back and forth several times, then lay down about thirty feet from the edge and appeared like a small, black spot. Shortly I saw, not a hundred yards distant to the right, in line with the snow, a band of twenty sheep feeding indifferently, though they had often looked toward the snow at the time when the bear had been moving. It was too hazy to clearly distinguish their horns, but I thought they were rams. Since it would have required many hours to descend and make the wide circuit necessary to climb, unseen by them, I did not attempt it, but watched them.

In half an hour they started single file directly for the snow, and to my complete astonishment walked up on it, not twenty feet from the sleeping bear. Eight that were ahead paused in the snow, apparently looking at the bear; then all slowly walked on over the snow and disappeared on the other side of the crest. Stranger still, as the first sheep came upon the snow, I saw the bear’s head rise up, until, as they stood still, it went down and the bear remained asleep long after they had gone over the crest.

After eating some lunch, I followed the sheep-trail for some distance along the crest, when I saw on an opposite mountain, separated from the one on which I was walking by a deep, narrow valley, a large band of sheep feeding well up the side. I counted about eighty in all, mostly ewes and lambs, with a few small rams. Descending over the steep, broken rock talus to a ridge, I walked along it until the sheep were not more than five hundred yards distant in a straight line across the valley, and, concealing myself among the rocks, I watched them. Some were feeding, some lying down. About ten three-year-old rams kept together, slightly separated from the rest. A hundred yards above was an old ewe lying on the slope, keeping an alert watch both up and down. In half an hour, when another old ewe walked up to her, she rose and went down to feed among the others, while the ewe above lay down to replace her as the “sentinel” to protect the band.

As the “sentinel”! Never was the posting of guards better illustrated; and what a positive conclusion one could have drawn if not especially aroused to continue watching and observing! Half an hour passed, while the sheep below were feeding, resting, always alert, and on the lookout for danger; the lambs were nursing and frisking. Then the “sentinel” rose, descended, and mingled with the others, leaving none on guard in her place

Thus entirely unprotected they continued feeding, until the lengthening shadows warned them of evening, and they slowly fed upward toward the crest to lie down for the night. During all the time that I watched them, the lambs kept playing, chasing each other, butting, and running back and forth.

I was so dose that through my glasses the colors of all the sheep were clearly discernible, and I carefully made notes in the small note-book which I carried. The majority of them were nearly of the same type as that of some of the Stone sheep killed on the Sheslay River north of Telegraph Creek on the Stikine, the skins of which are in the American Museum of Natural History in New York. From a short distance, the heads appeared perfectly white, the bodies light gray, intermediate in color between typical Ovis stonei and the saddle-backed sheep, so-called Ovis fannini. None had necks as dark as typical Ovis stonei, a few would be classed as Ovis fannini. Four were almost as white as the light colored sheep killed on the MacMillan. Several had lambs strictly resembling their mother in color. Four of the darkest ewes had white lambs. Three of the whitest ewes had very dark lambs. One dark ewe had two lambs, one white, one dark. The saddle-backed ewes had lambs, singly and in pairs, varying in all shades of color from whitish to very dark.

I was a long distance from camp and it was not possible to stalk the sheep without descending on the other side to the foot of the mountains, so that I could climb around the other mountain in a course which would keep me hidden from their sight. But since many days might elapse before rams could be found and meat had to be obtained as quickly as possible, I made the descent and began a circling ascent of the mountain. After three hours of slow and tiresome work, I was near the crest and carefully circled for the purpose of establishing the position of the sheep. At length, about to come in view of the place where I hoped to find them, I crawled flat on my stomach, and lifting my head saw all standing, banded closely together, about a hundred and fifty yards opposite me. About to lie down, they were taking one last look below. A large ewe stood a few feet to the right, and not caring to fire into the band, I aimed at her, and, fortunately, hit her in the heart. The whole band, led by a large ewe, at once dashed wildly along the slope and disappeared over the steep, almost vertical walls that flanked the slope slightly beyond. The ewe had no milk, and therefore no lamb. Her head was pure white and the grayish pattern was so subdued that the color could be compared most closely with the darkest specimen I had killed in the Ogilvies.

It was nearly eleven in the night; twilight color had overspread the landscape; the peaks distant to the west were still illumined with rosy light caught from the fading sun. Taking the hind quarters with as much extra meat as could be carried, I staggered downward to the foot, kindled a small fire, and made tea, which greatly refreshed me. I then shouldered the load and more rapidly went down the sloping pastures of the basin, until I plunged into the dense brush. It was among the dark hours that I toiled through the willows, and broad daylight again when I walked into camp at 3.30 in the morning. But we had a supply of meat; I had once more been high among the mountains; the sight of mountain-sheep and that of a grizzly bear had set glowing my love of the wilderness; I had again heard the chatter of the squirrel and the whistle of the marmot.

The shelter had been erected, and old Danger was peacefully lying before it, near the dead fire. Jeffries jumped up, and almost shouted when he saw the fat mutton. The fire was soon blazing and nothing less than as much meat as could be crowded into a big deep frying-pan satisfied his craving for it.

The Boone and Crockett Club is pleased to offer a new series of digitally remastered classic hunting and adventure books. Each book was authored by a member of the Boone and Crockett Club in the late 1800s or early 1900s and was hand-selected by a committee of vintage hunting literature experts. Readers will be taken back to a time when hunting trips didn’t happen over a weekend, but were were adventures spanning weeks or months.

You’ll be pleasantly surprised by the high-quality photographs and drawings from decades long gone that are scattered throughout these titles. This series includes books by renowned adventure authors such as Theodore Roosevelt, William T. Hornaday, Charles Sheldon, and Frederick C. Selous, to mention only a few. Available online at:

www.historyofhunting.com

www.boone-crockett.org