The mountain sheep of America are among the noblest of our wild animals. Their pursuit leads the hunter into the most remote and inaccessible parts of the wilderness and calls into play his greatest skill and highest qualities of endurance.

My first experience with sheep was in northern Mexico, where they dwell among the isolated groups of rugged mountains that rise abruptly from the great waterless deserts—deserts beautiful in their wealth of color, weird in the depth of their solitude, impressive in their grim desolation. It was there that I became fascinated by the exhilaration of the sport of hunting the wild sheep, and dominated by the desire of following them in other lands.

I was familiar with what had been written about the white sheep, Ovis dalli, of Alaska, and the darkest of the American sheep, Ovis stonei, of the Stikine water-shed in northern British Columbia; and when in 1901 still another form of sheep, Ovis fannini, was described from the ranges of the Canadian Rockies in Yukon Territory—an animal with a pure white head and gray back—I decided to explore for it if the chance ever offered. Indeed, so little was known about the variation, habits, and distribution of the wild sheep of the far northern wilderness, that my imagination was impressed by the possibilities of the results of studying them in their native land. There was, besides, the chance of penetrating new regions, of adding the exhilaration of exploration to that of hunting, and of bringing back information of value to zoologists and geographers, and of interest to sportsmen and lovers of natural history.

The opportunity came in the summer of 1904. A party was organized composed of the artist, Carl Rungius, who has so faithfully painted our large game animals in their true environment; Wilfred H. Osgood, of the Biological Survey, a trained naturalist of reputation, and myself.

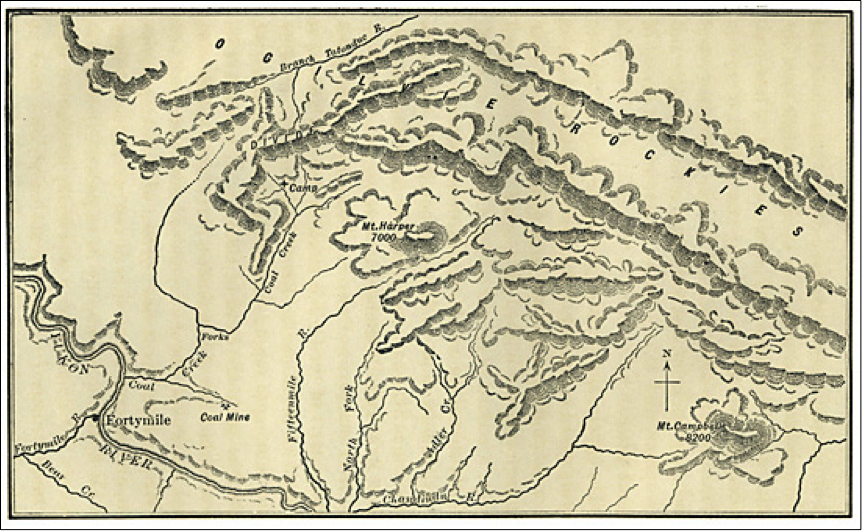

Late in June we sailed from Seattle and proceeded over the well-known route to Dawson, purchasing provisions for the trip in Skagway, and going over the White Pass and Yukon Railway to Whitehorse, where we took one of the large river steamers to Dawson. Learning that the game in those parts of the Ogilvie Rockies east of Dawson, at the head of the Klondike River, had been disturbed by winter hunting to supply meat to the Dawson market, we decided to go to the head of Coal Creek, which has its source in the heart of an unknown part of the Ogilvies, and enters the Yukon about sixty miles below Dawson.

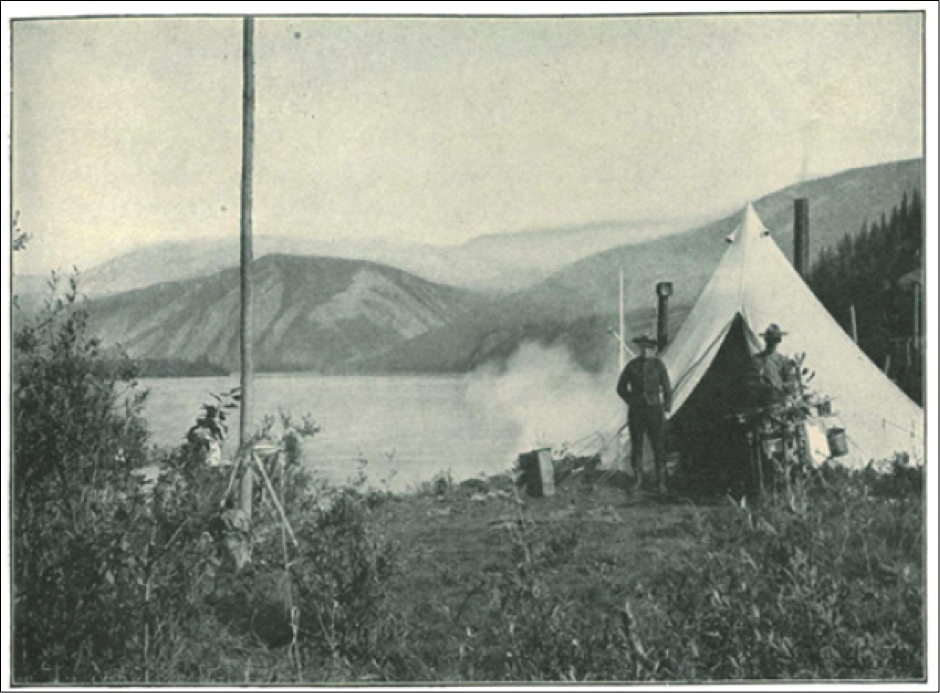

We purchased six horses together with packing equipment, and secured the services of two men, Charles Gage and Ed Spahr, to accompany us as packers. After several days of tedious delay, it was finally announced that the small steamer Prospector would start down river at 5 P. M., July 7. In due time, therefore, we loaded our horses and outfit on the boat, put on our hunting clothes, and went aboard just before the Prospector pulled out from the wharf on scheduled time. We soon passed through picturesque parts of the river where it narrows and runs between high cliffs, and farther down between high rolling ridges on each side, until at 8:30 P.M. we reached Forty Mile. Going ashore, we tried to get information from some of the residents as to the abundance of game and the possibility of travelling up Coal Creek. It was freely given, but conflicting. After a short stop at Forty Mile we left with a vague idea that it would be best to follow up the main branch of the creek and push on till we found the sheep country. We soon reached the mouth of Coal Creek, six miles below, tied up to the bank, unloaded our horses and outfit, and erected our tents on a high bank close to the water.

One of the Northwest Mounted Police was located there, living in a tent, doing his own cooking, and remaining practically inactive until the fall, when the river is closed to navigation. He was there to police the coal mines and keep a check on all people passing down the river who had not reported at Forty Mile. Though this practice stopped soon after, during the first years of the rush into the country, the Northwest Mounted Police, distributed at intervals along the Yukon River, took the names and destinations of all people passing in boats, summoning them to the shore if necessary, and kept a fairly good record of all who were travelling in the country.

Coal had been discovered a few years before, twelve miles up the South Branch of Coal Creek; and two years previous to our arrival, a mine was opened, coal chutes and boarding houses for men were erected at the mouth of the creek, and a narrow-gauge railroad was loosely constructed up to the mine. During the summer a small steamer kept hauling barges of coal to Dawson to accumulate it there for the winter supply of fuel.

At this point the Yukon River bends in a sharp curve and is surrounded on all sides by fairly high mountains, which may be the cause of the constant rain at that exact spot, even when the sky is clear a few miles above and below. Not more than a mile below, a spur of the main interior range rising about three hundred feet above timberline, extends nearly down to the river, and sheep are said sometimes to wander there in winter. I heard that there was a well-defined sheep trail on the top. Game is very scarce everywhere along the Yukon, but occasionally a black bear is seen, and in that particular vicinity I learned that one had shortly before appeared on the opposite side of the river; also that two had been killed a few miles up the railroad. Moose at times are seen along the river, and just below Coal Creek is a canyon, extending down between ridges from the mountain spur, where a few days previous the Indians from Forty Mile had killed a cow moose. By invitation I slept in the tent of Mr. Jones, the policeman; but before retiring we had tried to get some information about the interior country from various men employed on the railroad and at the mines, only learning, however, of one point where we should leave the railroad to reach the main branch of Coal Creek.

Photograph by Carl Rungius.

July 8 — As we were cooking breakfast early the next morning, it commenced to rain and, much to our disgust, continued all day. We could not start with horses that were “green” and too tender to endure the pack with wet backs and, besides, the trail began in a swamp. Hence the day was passed testing our rifles and wandering about with shot-gun and fishing rods. A few graylings were taken, and this first tramping gave us an impression of the difficulty of taking pack-horses through the thick woods. Osgood had a large supply of traps for small mammals, and it was his object to collect as many of the mammals, birds, and plants as possible. Many people visited us in camp that evening, but none could give the coveted information which might assist us to find a good route into the country we wished to reach.

July 9 — In the morning we were up at five and, after breakfasting, packed the horses and made a start, following an old road through a swamp, very muddy and soft, to the railroad tracks half a mile above. The horses, unused to packing, were very excitable and did not go well. They were all large and had been used in the winter stage service between Dawson and Whitehorse until each had become unsound and disqualified; yet they were still serviceable for pack-horses—at least, they were the best we could get. Caribou, an old white horse once used for packing over the White Pass trail, proved to be sagacious, very sure on his feet, the best “rustler” of all, and very quickly became the leader when they were turned loose. Old Mike, a bay, was steady and gentle, fairly sure-footed, but rather slow. Danger, a large bay, had never carried a pack. He was sure-footed, willing, but had an annoying habit of constantly picking feed when being led, and the conformation of his back was not adjustable to the aparejo, which kept it sore all the time. Nigger, a black, had never carried a pack, was clumsy on his feet, and had a tendency to jump at critical places. Shorty, a dark bay, was the best pack-horse of all. He followed well without leading, and though constantly lying down at every pause, would get up without shifting his pack. He was the pet, and always kept nosing about for sugar and bits of bread. Schoolmarm, a dark bay mare, not accustomed to the pack, carried a Mexican saddle on which were packed trifles and lighter material. Each of us travelled on foot leading a horse, while Shorty was driven ahead of the man in the rear. None of the horses had worked for a long time, and the first day was very trying for them. All kept lying down at every opportunity, thus showing great distress under their packs; it was difficult to lead them, and leading was necessary in that country.

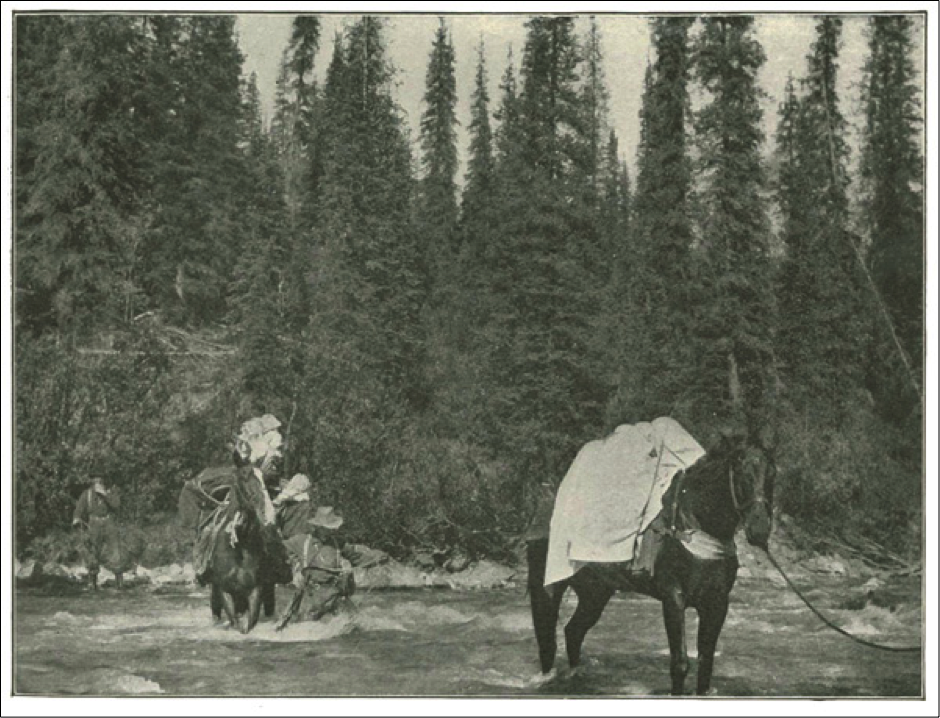

Photograph by W.H. Osgood. By permission of the U.S. Biological Survey.

Soon after emerging from the swamp and coming out on the railroad tracks, we reached Coal Creek and first learned the difficulty and danger of fording. The stream was swift and deep, and Rungius, falling in the ford, was nearly carried down. Again we passed through a swamp for two and a half miles, and, coming out on the track, proceeded up the railroad and arrived at some log cabins, called Robinson’s Camp, twelve miles from the mouth, about noon. While we lunched, a prospector who was loitering about, volunteered to show us the way to the main branch of the creek, and in the afternoon we again started, reached the creek, forded it, and found a blazed trail on the opposite side which we followed all day as best we could, now and then losing it and going on independently. The woods were dense and most of the ground was covered with soft, dry sphagnum moss through which the horses would sink six inches or more at each step, and which made the travelling tiresome for ourselves. We encountered this soft mossy ground at intervals most of the way. It is common on the sides and even the tops of the mountains until well into the divide ranges. Small spruces always grow in it, and, in places, huckleberries. Fording the creek back and forth, often chopping small trees and thick brush, we kept on until evening, when we found a little grass for the horses and camped by the side of the creek. It was daylight all night, except for three hours about midnight, as the sun went below the horizon, and then, for a short time, there was a fine twilight.

Thus far along the creek were balsam, poplar, white spruce, willow, and alder trees; flowers of various kinds and vetches were abundant. The creek was from sixty to a hundred feet wide; its banks were in some places rough and steep, and in others bordered by long, rocky bars. The mountains, covered with spruces, rose from the level country below, about a mile back from the river on the north side, and nearer to it on the south. The river was swift and deep; the temperature of the water about forty degrees Fahrenheit. During the day we noticed a few very old moose tracks and bird life was scarce. We only saw a pair of solitary sandpipers, a few spotted sandpipers, some Alaska jays, and a rough-legged hawk. After we had pitched the tents and had some tea, I took my rifle and went up the creek, but returned after two hours, having seen no signs of active animal life except a few birds.

July 10 — We packed and started late the next morning, still endeavoring to follow the blazed trail, which we had been told would lead to an abandoned logging camp, sixteen miles up the river. Here and there we could pick it up and follow it for a short distance, but most of the time we travelled independently, following the bars of the river, fording it many times, while the woods on both sides were so thick that Gage was constantly obliged to go ahead and cut a trail so that the horses could get through with their packs. Rungius and myself wore leather moccasins, the worst possible footgear in which to ford these northern rivers, where the current runs from six to ten miles an hour over an extremely rocky bottom on which the smooth moccasins slip almost as if on ice. In many places it would have been dangerous to fall, since a foothold could not be regained and one might become entangled in the driftwood or hurled against rocks while being carried down the continuous rapids. The others wore hobnail shoes, the only thing in which to travel along rocky rivers which have to be forded. Time after time we saved ourselves from falling by holding onto the horses, for they had no difficulty in keeping a solid footing.

Most of the day was perfect, though a light thunder shower fell in the evening. Soon after starting we saw the old track of a black bear; later we killed a porcupine and two Alaska Spruce grouse. We ate the porcupine flesh that night and found it excellent, though rather too rich. The character of the country continued the same, and a few birches began to appear where we lunched. We were somewhat worried because of the scant grass for the horses which, however, had become more accustomed to their packs and were going much better. A small black gnat now appeared, and greatly worried them, attacking their chests, bellies and legs, and causing the blood to run freely. Temporary relief was afforded by rubbing them well with wagon grease, brought for this purpose. One horse had cast a shoe and after replacing it we kept on through mossy, swampy muskeg that lay on both sides of the creek, until camp was made near some low but very rough mountains which came close to the creek. The creek continued to be of about the same width, and as we approached the mountains its abrupt descent made the fording more difficult. We slept at eleven, and did not start until 11:30 in the morning.

July 11 — Getting breakfast, gathering in the horses (which, owing to the scanty grass, had to range some distance for feed), and packing always required two or three hours or more. Having completely lost all signs of the blazes that marked the route, we worked our way up the creek for a mile to a point where rocky bluffs shut in so close that we were obliged to climb around them and proceed along a steep mountain side. While wading the horses around a point in the stream, where it dashed in rapid descent through a rather wide canyon, Danger, the horse in the lead, went around safely, but Nigger lost his footing and fell in the water, so that we were compelled, after getting him out and fixing his pack, to go on with these two along the bank, not caring to risk returning around the point. The other horses were not permitted to attempt it and were taken up the slope on a good game trail. It was necessary soon to take Danger and Nigger up a very steep ridge where Nigger lost his footing and rolled down about fifty feet. The pack was uninjured, but we had to remove it and use Danger to take it up the incline. Then, when trying to lead Nigger up, he again lost courage and, rearing, fell backward and rolled down some distance, but received no injury other than a bad cut on a hind leg, which later did not seem to trouble him. All this made considerable delay, but finally we again got under way and soon found a good game trail on the slope along which, with some chopping, we passed and descended into a swamp where we picked up the blazed trail. This swamp continued some miles and was extremely difficult to travel through. Fortunately, it had not rained sufficiently to make it impassable and we were able to get through, though not without much exasperating delay, owing to the bogging of the horses and the consequent repacking or constant readjustment of the packs.

Late in the afternoon we emerged at a point where Coal Creek forks; the main branch coming from the north, the other of almost equal volume from the west. A few hundred large spruce trees near here had been cut the preceding winter, and most of the logs had been driven down in the spring to a movable saw-mill, where they were sawed into lumber to be used in the coal mines and docks. At the Forks we saw two king salmon, which were just beginning to run up the creek. Soon two men appeared, who had come more directly across the country from Robinson’s Camp the same day, to count the remaining logs piled on the bank near the river. They could give us no information about the country farther up, except to say that five miles ahead there was a canyon which would block the progress of pack-horses, and beyond it the mountains were too rough for our method of travel. Here, at last, we found an abundant supply of good grass for the horses, and from there on it was plentiful and of good quality. Mosquitoes were beginning to be bothersome, though not yet a pest. The country was wilder; the mountains, which rose in ridges and formed spurs of the main range, were nearer the creek and were covered with spruces and poplars.

After taking a bite to eat, I started with my rod to try for graylings in front of the cabins, and quickly landed seven of fair size from one pool. Graylings were abundant in all the large pools clear up to the head of the river. I even saw several a half mile below the melting snow, near the extreme source of the creek. Those caught usually averaged from eight ounces to a pound in weight. They are quite shy and generally lie at the foot of the more rapid water of the pools or in the eddies—always where the surface is smooth. They quickly start to take the fly, but with no snap, just rising to the surface to grasp it in a sluggish manner, and once hooked they have no more play than a chub. I have never found them a game fish or worth catching except for food, and then only when other meat is lacking. As a fish for the frying pan they are most inferior, for when cooked they are soft and have not much flavor. It is said that later in the fall they become harder, and perhaps that is so, but on the whole I am convinced that they could never satisfy the taste of one accustomed to trout, bass, or even perch. Still, they do afford a relief from bacon and beans, and when travelling in the north I have always been glad to get them. After catching a mess of grayling, I took my rifle and made a wide circle around a ridge behind the cabins, seeing abundant old moose tracks, two or three olive-backed thrushes, and a few juncos and red squirrels. Returning to camp about 10:30 at night I took the rod again and quickly captured three more graylings from the same pool, even after Rungius had just caught some before me. At 11:30 I rolled under my blanket, beginning to realize that the continual daylight caused irregular hours. It did not, however, interfere with sound sleep.

You’ll be pleasantly surprised by the high-quality photographs and drawings from decades long gone that are scattered throughout these titles. This series includes books by renowned adventure authors such as Theodore Roosevelt, William T. Hornaday, Charles Sheldon, and Frederick C. Selous, to mention only a few. Available online at:

www.historyofhunting.com

www.boone-crockett.org