Some of us are dreamers, in admiration—occasionally in awe—of the doers of the world. The challenges of life, the prioritization of making ends meet and satisfying the needs of others, often trump the pursuit of our own childhood dreams. Still, we humans are perpetually capable of changing course, adapting, and making things happen. Doers (large and small) in this sense are the very few who manage to squeeze more drops out of this brief existence—whether it be through greatness, some notable achievement, or more often through good deeds and memories shared. Their stories lend perspective, community, inspiration, and motivation to others.

Through brilliance, vision, hard work, inner drive, or just some really good decisions, in these doers we can expect to find much in terms of sacrifice—and failure as well. These elements are often the stumbling blocks of mere dreamers. The doers maintain a certain spark and do not give up. Often, it’s in the taking of the obscure tributary, the path of great resistance to a highly uncertain outcome that we truly challenge ourselves. At times, even us dreamers experience and achieve greater things than our vast imaginations conjure up along the way.

Because of this, dreamers can always be reminded of possibilities—of alternative outcomes—that may be even better than our dream scenarios. Doers tend to take on the risks and low probabilities because of, rather than in spite of, these uncertain outcomes and potential failures. Further, humans own the power of the narrative, and in that the potential for great inspiration as well.

Perhaps for the non-sheep hunter, it is in the tales of mental stamina and sheer determination, the physical challenges and frequently extreme conditions, and the truly rarified air and surrealistic landscapes of the domain of the wild sheep of the world that we are awakened and challenged to think bigger and do more. The story, or just the image, of the grizzled hunter with a hard-won ram can re-ignite the pilot light of our individual dreams—for hunters and non-hunters alike.

We’re all dreamers and doers in our own lives and circumstances. Further, we can always be inspired to expand our horizons and explore beyond our physical or psychological boundaries. Heck, even this kid once drew full-curl rams and sculpted them from clay. Maybe he can still climb a mountain and see the sheep from afar in some vast and isolated high country wilderness. That would be a start—possibilities and inspiration!

A Brief History of the Sagamore Hill Award

As noted on the Boone and Crockett Club’s website:

The Sagamore Hill Medal is given by the Roosevelt family in memory of Theodore Roosevelt (founder and first president of the Boone and Crockett Club), and his sons, Theodore Roosevelt, Jr., and Kermit Roosevelt.

It is presented as an exemplar symbol of the Boone and Crockett Club’s principles of conservation, fair chase hunting ethics and records keeping. Since its creation in 1948, this highest award has been bestowed upon only 17 fortunate hunters, in recognition of an outstanding North American Big Game “trophy worthy of great distinction” taken by them. For the most part, this honor has been assigned for mature animals with the highest scoring antlers, horns, or skull of a given species recorded under the B&C measurement system and rules of fair chase at the time of the award.

Year

1948

1949

1950

1951

1953

1957

1959

1961

1963

1965

1973

1976

1986

1989

1992

2001

2010

Hunter

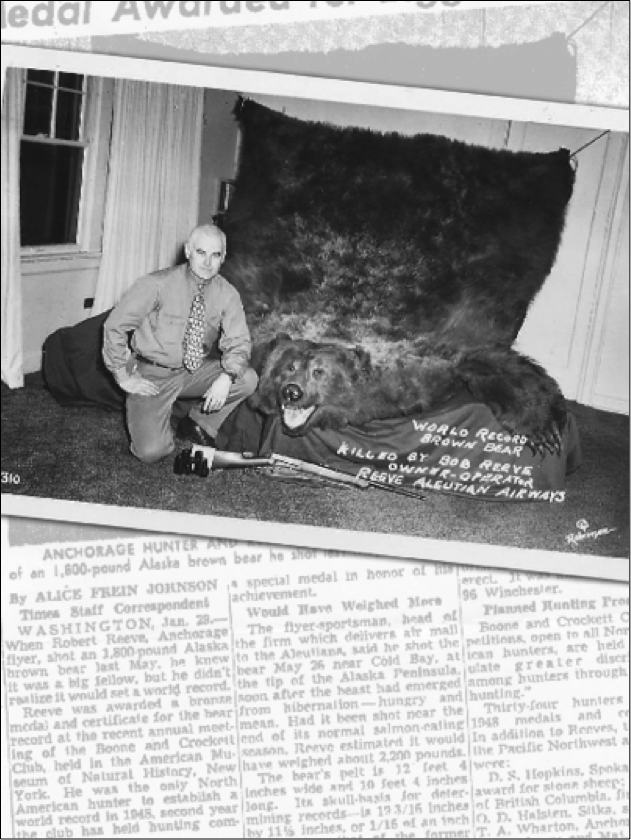

Robert C. Reeve

E.C. Haase

Dr. R.C. Bentzen

George Lesser

Edison Pillmore

Frank Cook

Fred C. Mercer

Harry L. Swank Jr.

Norman Blank

Melvin J. Johnson

Doug Burris Jr.

Garry Beaubien

Michael J. O’Haco, Jr.

Gene C. Alford

Charles E. Erickson Jr.

Gernot Wober

Paul T. Deuling

Category

Alaska Brown Bear

Rocky Mountain Goat

Wapiti

Woodland Caribou

Mule Deer

Dall’s Sheep

Wapiti

Dall’s Sheep

Stone’s Sheep

Whitetail

Mule Deer

Mountain Caribou

Pronghorn

Cougar

Coues’ Whitetail

Rocky Mountain Goat

Mountain Caribou

Score

29-13/16

56-6/8

441-6/8

405-4/8

203-7/8

185-6/8

419-4/8

189-6/8

190-6/8

204-4/8

226-4/8

452

93-4/8

16-3/16

155

56-6/8

459-3/8

However, this select group possesses even more momentous situations when one goes beyond the exceptional trophy and takes into account the hunters and their unique stories. Among these are the two top-ranking Dall’s sheep taken by Sagamore Hill Award winners Frank Cook and Harry L. Swank, Jr. The No. 2-ranking ram was taken by Cook in 1956. At the time of his Sagamore Hill Award in 1957, his trophy ranked No. 1. Swank’s ram, taken and awarded the honor in 1961, has stood as No. 1 since that time.

Wild sheep and a relatively few other creatures survive and thrive in occasionally gravity-defying and inconceivably gorgeous wild places. For all lovers of the outdoors, these are the places the dreamers want to be, and the doers actually take on, come what may. As such, larger-than-life stories are more likely to emanate from this world. And in these unique hunter’s stories—and in the other select Sagamore Hill Medal winner’s stories elsewhere in this book—readers can find hopes, patience, planning, effort, pursuit, and the place where circumstances collide at the intersection of life events, dreams, and statistical improbabilities. Such is (or can be) life.

Epic Accounts of the Top Two Dall’s Sheep

It is notable that of the top-50, top-25, and top-10 Dall’s and Stone’s sheep qualifying and recorded in the Boone and Crockett Club’s records, only a comparatively few have been taken by hunters since 1970, let alone since the year 2000. This is shown (see table opposite) in sharp contrast to the number of exceptional bighorn and desert sheep taken in these more recent periods. For example, since 1970, almost 80 percent of the top-50 bighorn sheep, and just over two-thirds of the highest-scoring desert sheep have been harvested. The same analysis reveals that only 16 percent of the top-50 Dall’s and Stone’s sheep have been taken and added to the records over the last 34 years. This factor alone makes the top Dall’s and Stone’s sheep that much more unique and important from a historical perspective. It also raises questions as to the determinants contributing to these distinct differences in statistical trends.

One could surmise from the records data that bighorn and desert sheep populations have long outnumbered those of the Dall’s and Stone’s sheep—at least in terms of huntable numbers of the species. Further, and again overly simplistically, it would at least appear that bighorn and desert rams have experienced comparatively improving habitat and living conditions (i.e. the ability to attain old age and large horns) since 1970 versus Dall’s and Stone’s sheep. Whether or not these factors are relevant in terms of B&C’s records and the status of wild sheep populations, the observations as to the top-trophy rankings is nonetheless very intriguing.

In all likelihood, a wide array of determinants, including the suppositions regarding relative species abundance and then-versus-now habitat and survival rates are involved. During the post-World War II years, for example, the increasing penetration of Alaska and the Canadian province’s mountains and tundra by small, private aircraft very well had a direct bearing on the sheer number of Dall’s and Stone’s sheep accessible and taken by hunters. Given this relatively new mode of transportation, the added efficiencies (faster travel and therefore fewer required hunting days) made selective hunting a far more viable option as well—adding specific pressure to the older age class rams. These factors, in turn, were strongly supported by a return to domestic economic prosperity during the 1950s and ‘60s.

The factors noted above do not consider many other positive or negative contributors. These could obviously include human population dynamics, habitat deterioration, industrial exploitation, impacts of regional game laws, numbers of licenses or tags sold, and other variables likely to affect the various sheep species’ fortunes.

In any case, the Dall’s and Stone’s sheep appear to be the relative underdogs of the four North American wild sheep species today. This has not gone unnoticed by the Wild Sheep Foundation (WSF). In the July/August 2014 issue of Sports Afield, an interview with WSF’s CEO and B&C Professional Member Gray N. Thornton included the following comments:

“The range of thinhorns (Dall’s and Stone’s sheep) is largely intact. There are challenged areas, though.”

He went on to note that the organization recently held a Thinhorn Summit to devise an action plan for the two subspecies across their ranges in both Alaska and the Canadian provinces. As with their Lower 48 and Mexico sheep brethren, disease transmission from domestic sheep and goats is the biggest threat to sheep populations. In addition, and more specific to Dall’s and Stone’s sheep, it is believed that a lack of comprehensive management plans for sheep populations, as well as a need to better manage all-terrain vehicle access to remote areas, are key issues to be addressed on behalf of these great sheep.

The Swank and Cook rams, taken five years apart, obviously share much in common with other top-scoring Dall’s sheep. These characteristics are primarily long horn curl (for example, of the top-50 scoring Dall’s rams, the longer horn in almost all cases exceeds 45 inches), heavy horn base circumferences (generally greater than 15 inches), and above-average quarter circumferences as one moves around the horn. Horn length for these two rams is outstanding. In fact, the Cook ram’s longer horn, at 49-4/8 inches actually exceeds the comparable measurement of 48-5/8 inches for Swank’s ram. (See table above for additional details.) Only one other Dall’s sheep, the No. 3 ram taken by Jonathan T. Summar, Jr., in the Alaska Range in 1965, possesses a single horn curl measurement exceeding 48 inches. Two other rams in the records have a longer horn that just makes the 48-inch mark.

Horn curl, also called the length of horn measurement on the scoring sheet, provides an interesting natural dilemma at times. This is true for the scoring of all North American wild sheep horns under the Boone and Crockett scoring methodology. Older bighorn rams in particular tend to naturally broom or damage horn tips during their lives (including battles with other rams vying for dominance). Missing horn cannot be measured, so it is lost to the wild—and to the final score.

Interestingly (and fortunately), this often-exhibited brooming, or broken horn asymmetry is not doubly penalized by the Boone and Crockett’s scoring system. This is notable, as side-to-side symmetry is a significant component of the overall B&C methodology. In the case of sheep, horn curl length is equal to “all that is there.” In other words, there is no additional scoring penalty for the difference between a 45-inch horn on one side, and a 42-inch broomed horn on the other side. The score credit for this example is simply 87 inches, rather than 84 inches if the difference between the two were subtracted in the final scoring calculation.

The latter scoring credit, or 84 inches from the example above, is not the case for differences in horn length for the remaining horned big-game species. For example, if a Rocky Mountain goat’s horns are naturally symmetrical, great, but if one is shorter than the other, or broken off, the difference between the two horns is subtracted from the final score. That is because it wasn’t grown (shorter) or is missing (broken). Sheep are therefore given the benefit of the doubt that horn length is likely asymmetrical in direct relation to the tendency for broomed horns, especially in mature bighorn and desert rams.

Therefore, B&C captures the bulk of the visual symmetry—or balance—for exceptional sheep in its circumference measurements. For the Swank and Cook rams, deductions of only 5/8 and 7/8 inches, respectively, were taken for circumference asymmetry. As with broomed or broken-horn tips, circumference measurements may be thrown askew when chunks of horn are missing, often as a result of fighting. Specifically, no score credit can be given for missing horn sections at the points at which circumference measurements are taken.

Taking this measurement observation to an extreme (specifically for Dall’s and Stone’s sheep), we compare the top-ranking rams with a hypothetically perfectly symmetrical ram scoring 180 inches, which would place it in the top-23 rams in the B&C All-time records as of this writing. Assuming 45-inch horn lengths, half of the total score would be from horn length, and the other half from circumference measurements.

Horn length and mass are certainly key wow-factor elements when comparing sheep horns, especially when viewed side-by-side. This is particularly true when looking at two otherwise full-curl rams, where one carries either heavier base circumferences and/or heavy mass all the way around the curl. However, a missing element that can also make outstanding rams’ horns visually stunning is the widest spread of the horns, though this purely aesthetic characteristic is not factored into the overall scoring calculation.

The Boone and Crockett Official Measurers manual notes that sheep horn conformation may be any of three basic types: the close curl, a close curl with flaring tips, or wide-flaring horns. Thinhorn sheep, like the Dall’s and Stone’s species, tend to exhibit less brooming and damage than their bighorn or desert sheep counterparts. Conversely, they tend to display more variation in conformation and flare, which in turn decreases or increases outside spread. Greatest spread and tip-to-tip spread, while recorded on the official B&C score sheet, are not added to final score. This is important, as the range of basic horn conformation would discriminate against rams with close curl and lack of tip flare versus those possessing flaring tips or wide-flaring horns.

Therefore, and of special note as it relates to the Swank and Cook rams, two trophy sheep with comparable horn length and strong circumference measurements can still look very different. This is based on the tightness of the horn curl and/or how the horn tips flare out to create a total, visual outside dimension. In this specific case, the Swank ram’s widest spread is a full 10 inches greater than that of the Cook ram. The specific measurement for Swank’s sheep is 34-3/8 inches, versus 24-3/8 inches for Cook’s.

Thirty hunters. Thirty record-book trophy big game animals, most of them taken without guides on public lands. Thirty epic tales to share back at hunting camp. These are the real-world stories behind some of the top-scoring trophies ever recognized by the Boone and Crockett Club.