The sheep were on the bare steep slope of a mountain four or five miles away, and even through the binoculars they looked like no more than five small white specks.

“It’s too late to get over there today,” Frenchy Lamoreaux grunted, “and I’m not for siwashing in the open overnight unless we have to. I’m gonna move up ahead and have a look at that draw we saw from lower down. There might just be a ram in it.”

“You go along,” I agreed. I don’t think any more of siwashing than you do, but I want to look those sheep over with the spotting scope before I pull out. Five together could be all rams, and there’s always the chance of a good one in a bunch like that.”

Frenchy moved off. I set up my 40x scope, stretched out prone behind it, and went to work on the far-off band of sheep. I was lying on a deep-cut sheep trail just below a 7,000-foot peak, and the weather that afternoon wasn’t exactly mild. An icy wind poured over the ridge above me, howling like a banshee, and even on the low tripod that supported it, I couldn’t hold the scope steady enough for a good, clear look.

So, I rolled aside, scooped out a shallow depression in the rocky ground, set the tripod on it, and braced the scope with my packboard. That did it. I could get a good look at the five sheep now, and I studied them one by one.

The first three were just sheep—white blobs on the green-streaked, slate-gray slope. Though the scope was magnifying them 40 times, they were too far away for me to make out horns. Then something happened that made me suck in my breath. When I moved the scope to the fourth, I saw, clearly and distinctly even at that distance, the dark curl of horns.

I knew that I was looking at a Dall’s head of far better than average size. I rested my eyes, then took another look to make sure the light and wind weren’t playing tricks on me. The horns were still there, and when I rolled away from the scope my mind was made up. That ram was the kind I’d come for, and if he’d stick around I’d get him if it took me the rest of the season.

Frenchy came back within an hour and we headed for camp. Weather permitting, we agreed, we’d make our try the next morning. We’d get an early start, for this was going to be no easy mission.

The time was late August, 1956. Frenchy, Wally Wellenstein, and I were camped in the Chugach Mountains, north of Anchorage, Alaska. We were after one thing and one only, Dall’s sheep, and we wanted good heads or none. We’d already had enough action and excitement to make the hunt stack up as a worthwhile venture. Now it seemed likely we were getting close to the climax.

I’ve enjoyed hunting since I was old enough to lug a gun, and Alaska has been in my blood as far back as I can remember. I grew up in New York, and there’s some nice outdoors there, but the idea of one sprawling mountain range big enough to cover that whole state always appealed to me. So, it was only natural, when I finished at the University of Denver after a hitch in the Navy, that I should head for Alaska. My work was to be that of tax consultant and investment representative, but I saw no reason why I shouldn’t combine my favorite pastime with it. I settled in Anchorage in 1951, and still live there with my wife and young son.

I hunted moose my first season in Alaska, dropping a good Kenai Peninsula specimen with one shot from my .300 Magnum. Then I set my sights on Dall’s sheep, the milk-white thinhorns of Alaska and Yukon heights. A Dall’s ram is one of the world’s finest trophies—and correspondingly hard to get.

My first few sheep hunts were disappointing, but they taught me a lot. I learned that my daily office routine was poor training for climbing jagged heights until the clouds were below me. Regular sessions of roadwork fixed that. I trained before each hunt until I could run two miles in 16 minutes and tote a 100-pound pack a mile without stopping.

In my years of apprenticeship, during which I killed three fair Dall’s sheep, I learned to travel light, relying on dehydrated foods and a minimum of light, but sturdy gear. Experience taught me to allow at least 20 days for a backpacking sheep hunt. Sheep-country storms can keep you in camp for days. You need time to wait out the weather.

I gradually acquired the right kind of optical equipment—light 7×35 binoculars and two spotting scopes, 25x and 40x. The 25x is for those warm days when the more powerful 40x picks up heat waves that distort objects.

I spent a lot of time planning for my 1956 hunt. This was to be the hunt for an outstanding trophy. If I couldn’t locate a real buster I’d hold my fire.

After many talks with hunters, hikers, pilots, and prospectors, I settled on the Chugach Mountains as the place most likely to give me the kind of head I was looking for. I’d first hunted there in the fall of 1955 with Red Mayo, a former Maine guide. Sweating under heavy packs, Red and I had spent three days climbing up to that sheep range. That was too much.

I couldn’t bear to think of walking in there again, so when I was ready for my hunt the next fall I decided to fly in to a small mountain meadow that was within easy walking distance of what I knew to be top-notch sheep range.

Red couldn’t go, so I talked Wally Wellenstein into taking a week off to hunt with me. I felt a little guilty about it, for I wondered how we would salvage his job with an Anchorage architect firm if we stayed the whole 20 days I had in mind. But Wally didn’t seem worried. He’s lived in Alaska since 1949, has spent most of his spare time hunting, and won second place in the 1953 Boone and Crockett Club competition with a polar bear.

Sheep season would open on Monday, August 20, so we made a date with Jack Lee, a local guide and pilot, to fly us to our base camp site the preceding Saturday. This would give us a couple of days to get camp established and scan the country for sheep. It was a beautiful morning for our flight, and as we bounced along through the rough air currents, we picked out bands of sheep on the green slopes and high meadows below. Jack set us down on our chosen airstrip, and after we’d unloaded our gear he took off into the morning sky and headed back to Anchorage. So far as we could see we had the whole Chugach Range to ourselves.

We spent the first day near the meadow where we’d landed. I’d hunted there the fall before and sheep were plentiful, but a year’s time had brought changes. It was quickly apparent that I wasn’t going to be able to keep the rosy promises I’d made Wally about good rams right around the airstrip. We saw four ewes and lambs that forenoon, and after lunch we checked a steep box canyon and spotted two rams, one three-quarter curl and one full curl, on the slides above us. Even the bigger one wasn’t an outstanding head, and anyway, it would have taken rope and pitons to get up to him. We wrote him off, and agreed our best bet would be to move camp to another area higher up.

We made the climb Sunday, lugging gear and supplies over glaciers and steep slides, detouring around vertical cliffs we couldn’t climb, wading ice-cold streams milky with glacial silt, and stopping frequently to rest and glass the mountains.

We saw nothing outstanding, and late in the afternoon we halted and made camp at the edge of a big snowfield just below the summit of a mountain. It was a bleak, wind-swept spot, but it had strategic value for us since it overlooked a long, beautiful valley, half a dozen hanging glaciers, and a tumbled range of cliffs and slides that looked ideal for sheep. And by climbing 200 yards to the top we could glass a vast area on the far slope.

We spent an hour or two glassing the country, and counted 23 sheep and 19 goats. Somewhat to our surprise, the goats were grazing lower down than the sheep. We were high enough to get at almost any band we chose, and we felt good about our prospects. “Looks as if we came to the right place,” Wally said.

The weather turned dirty as evening came on with fog, rain, and sleet. We rigged a windbreak of our packboards and a sheet of plastic, cooked supper in the lee of it, and at 7 o’clock, long before dark, we crawled into our sleeping bags to keep warm. We were ready for bed anyway—it had been a hard day.

I crawled out at 5 o’clock the next morning and broke an inch of ice on the water bucket. Breakfast consisted of side pork, stew and noodles reheated from the previous evening, bread and butter, and strong hot coffee. We figured we needed a meal that would stick to our ribs, for sheep season was open now and big doings were afoot.

We decided to try the far slope, across the glacier, where we’d sighted two good size rams—one conspicuously bigger than the other—the afternoon before. It was Wally’s first sheep hunt and he was pretty keyed up.

We crossed the glacier in the early dawn as ribbons of fog rolled up out of the valley like gray smoke. On the far side we stopped to do some glassing, and within five minutes picked out our two sheep feeding on an open slope a couple of miles away, about where we’d seen them the previous day. We felt they’d probably hang around and wait for us if we didn’t spook them.

The stalk promised to be a tough one. The wind was in our favor, but there was little cover and no way to approach out of sight of the rams, either below or above them. We worked along as carefully as we could, taking advantage of draws and ravines to make brief rests. The last 1,000 yards we moved over slowly, inching along when the rams turned their backs or lowered their heads to feed, halting whenever they looked our way. By now we could see that the bigger of the pair had remarkable horns.

Four hours from the time we left camp we were close enough for a shot. The earlier overcast weather had broken, and shooting light was perfect as we crawled to the top of a low hummock 130 yards below the nearest sheep. The bigger ram was high on the crown of the slope, while his smaller companion grazed nearby in a small hollow. The situation couldn’t have been better for us, since the lower sheep was out of sight, except for the top of his back, and there was no danger of spooking him.

Since I’d given the shot to Wally (because it was his first chance at a sheep), I readied my camera and dropped back a few yards, looking for a good vantage spot. But in that instant, while Wally’s head and shoulders were in sight over the hummock and I was creeping across an exposed slope, the ram threw up his head and saw us.

I froze in my tracks, still as a rock, and I think Wally held his breath. But it did no good—you can’t out freeze or outstare a Dall’s sheep. I lay on the steep slope in an awkward, cramped position, knowing it would be only a matter of minutes before I’d have to move. It was a question now of whether Wally could get off his shot before the ram figured us out and lammed.

Seconds dragged by while Wally slid his .30-06 Mannlicher up over a flat rock in front of him. I was holding my breath now. The ram was facing him head-on, and the curve of the slope hid all of the big white body except a patch of shoulder and the neck. I knew Wally wouldn’t risk a head shot, not on such a trophy as that. Would he miss altogether?

Then, while I waited for the slam of the rifle, the ram took things into his own hands. He wheeled and raced for a jumble of rock to his left, and the gun barked out its hard, whiplash report. The heavy bullet, centered squarely in the shoulder, should have knocked the ram off his feet. But it didn’t. He swung uphill, running as if he hadn’t been hit at all. Then the second shot missed a vital area but turned him back downslope, and the third dumped him in his tracks.

The head was a good one—in fact we didn’t realize just how good at the time. We admired the horns, thumped each other on the back, made a few pictures, and went at the job of caping and skinning, boning out the meat and protecting it in a cotton sack for the trip back to camp. It made a heavy load, but we were too excited to mind.

We were back on the glacier, within a mile of camp, when dense fog rolled across the ice without warning, and in half a minute we were socked in. I’ve always carried a compass on my sheep hunts, but it was of no use now, for the fog had come so swiftly I’d had no time to take a bearing. We could see neither sky nor landmarks, only the ice for a few feet around us, and no man in his right senses goes wandering around on a glacier under those conditions. There’s too great a chance of winding up at the bottom of a crevasse. So, Wally and I slipped off our packs and sat down. An hour later the fog lifted as swiftly as it had come. It could have been worse, for we might have had to spend the night on the open glacier.

We were almost back to camp, just before dusk, when we saw a magnificent ram on a mountain less than a mile away, and for a few minutes I thought I had my trophy. Through the 40x spotting scope I could see massive horns—the best I’d ever laid eyes on. But while we were making excited plans to go after him the first thing in the morning, he swung his head and gave us a look at his left horn. It was splintered back for more than six inches, and the instant I saw it I lost all interest. My guess is he’s as good as one-horned by this time, for if a challenger socked into him hard and solid during the rut last fall, that splintered horn is probably broken off.

I spent the next two days checking valleys, peaks, and canyons. I saw some fair sheep, but none I was willing to settle for. Wally, meanwhile, was making shuttle trips back to the airstrip with his trophy and part of the camp gear. Jack Lee had agreed to fly in each Saturday and check with us, and we decided it would be best for Wally to send his sheep back to Anchorage as soon as possible.

I helped Wally with the last leg of the shuttle late the second afternoon. As we set up camp at the airstrip shortly before dark, we found we had a neighbor, Frenchy Lamoreaux, an Anchorage guide who’d come in to scout the area for sheep and take a few pictures. Since Wally had his ram, Frenchy and I decided to team up for the rest of our stay, and I was to plan the hunt. We didn’t think it would be as short as it was.

We started seeing scattered bands of sheep right after we left camp next morning, but we encountered nothing of trophy size until late afternoon. Then, on a mountain far ahead, we spotted the five rams I mentioned in the beginning, one of which had an unusually large head. I felt confident, as we crawled into our bags that night, that the climax of my sheep-hunting experience was only a few hours away. I was up and lighting the stove for breakfast at 3 o’clock. We bolted a hearty breakfast, then loaded up and walked away from camp in the first gray light of a cold, rainy morning.

We traveled steadily for hours in the rain and biting wind, climbing in and out of canyons, skirting slides too steep to cross. The route we had picked led up through a high pass to the slope where we’d seen the five sheep the afternoon before. We crossed the summit in a roaring storm, with rain blowing up one side of the mountain and snow up the other. If our five rams hadn’t moved, we were getting close now, but an impassable snow ridge blocked the way above the pass. We’d have to drop down a shale slide and come up to the sheep from below.

We started down, skidding and loosening small avalanches of shale, but before we’d gone far we saw a band of 20 ewes and lambs on a slope at the bottom of the slide. To spook them into the five rams, assuming the latter were still in the neighborhood, would end our hunt, so we turned around and clawed our way back up the slide to look for another approach.

We found a well-worn sheep trail angling up toward the pasture where we hoped to make contact, but as we turned to follow it, two young rams came over the skyline above and marched down toward us. We were boxed in, with the big band below and this pair above. If any of them winded or saw us, the odds were good we could say good-bye to the five we were after. Reluctantly we turned off the sheep trail, climbing on steep, wet, slippery shale, and managed to get out of sight of the two that were coming down.

The rest of the way was almost straight up, and it was half an hour before we finally broke over the ridge—winded, rain-soaked, and tired. But it was worth the climb. The sheep pasture I’d studied through the spotting scope the afternoon before lay spread out in front of us now, a perfect haven for an isolated band of big rams. It was cut off from above by glaciers and snow, from below by rock walls too sheer to climb, and from the sides by shale slides and steep ravines. So far as we could see, we’d gained entrance over about the only possible route.

The sheep trail we’d started to follow came up the bottom of a ravine only a short distance below us. We dropped down and followed it out onto the open slope. Our five rams were nowhere in sight; but if they hadn’t left the pasture, we had to be very close. Another 10 minutes would tell the story. I could feel my heart thumping against my ribs, and I knew it wasn’t altitude alone that was doing it.

We were picking our way along, making no more commotion than two cats on a velvet rug, when suddenly we walked smack into a flock of ptarmigan. We had no warning. They materialized out of the hazy background of fog and rain, and perched on rocks on both sides of us. I held my breath, waiting for the usual cackle of alarm, knowing it might be all the warning the rams would need if they were close by. But not a bird called. Maybe the weather was too much for them, for they sat glum and silent, feathers fluffed out to fend off the cold rain, while we walked carefully on.

A little farther along a gray marmot streaked past us, racing for his den under a flat rock, and again I waited for the shrill alarm whistle that’s standard marmot procedure in such cases. But the marmot ducked into his hole without a sound, and we heaved a sigh of relief and went on.

I was a few steps ahead of Frenchy, and I walked onto the five rams the way you’d walk up on tame sheep in a pasture. I rounded a big rock and there they were, 100 yards below, standing shoulder-to-shoulder and looking straight at us. It was one of the most breathtaking sights I’ve seen in a lifetime of hunting.

I ducked back and stopped Frenchy, but not before the sheep had caught motion. They weren’t spooked but they were thoroughly alerted, and it wasn’t likely they’d hang around very long. We swung to the left, up a rocky outcrop to get into shooting position, and the instant we looked over we knew we had them flat-footed. To their left was a deep ravine that would shelter them for 150 yards, but they’d still be within range when it petered out, with another 100 yards of bare meadow to travel. If they went to the right they had about the same distance of open slope to cross. Whichever way they chose, we’d have clear shooting.

The seconds ticked off while we tried to pick the two we wanted out of the tight-bunched group. They were all good heads, but at the back of the band shielded by the rest, I spotted what I was looking for—a massive set of horns that would go a lot better than full curl.

The two rams farthest downhill broke first. They wheeled and went for the ravine, and I realized it was time to shoot. But the other three still waited, as if not quite certain where the danger lay or which way to run. The one I wanted was hidden behind his two companions, as I held the scope on all three and waited. Then the two out in front spun around and lit out after the first pair, and as they broke apart I got the chance I wanted.

The big fellow hesitated long enough for me to center my crosshairs on his shoulder, and the 130-grain Silvertip from my .270 King Sporter knocked him over as if mountain lightning had struck. But he didn’t stay down. He rolled a few yards down the slope, gathered his legs under him, and staggered to his feet. I hammered in another shot and he dropped.

Frenchy’s .30-06 bellowed twice at my elbow, but the ram he’d picked kept going across the open slope beyond the ravine, and I saw the range was pretty long for iron sights. I shoved my rifle at him. “Try this,” I said. “You can find him with the scope.”

He dropped his gun, grabbed mine and brought it up, but nothing happened. “It won’t shoot,” he howled, and I realized I’d flipped the safety on automatically after my second shot. I reached across and thumbed it off. The ram had only about 20 yards to go now to get out of sight, and was pouring on coal. I didn’t think Frenchy was going to make it, but at the bark of the .270 the sheep nose-dived into the shale and rolled end-over-end.

When I looked back at my own ram he wasn’t as dead as I’d thought. He was up on his forelegs, dragging himself down the slope. I yanked my rifle away from Frenchy and put a third shot into his spine, and he was mine for keeps.

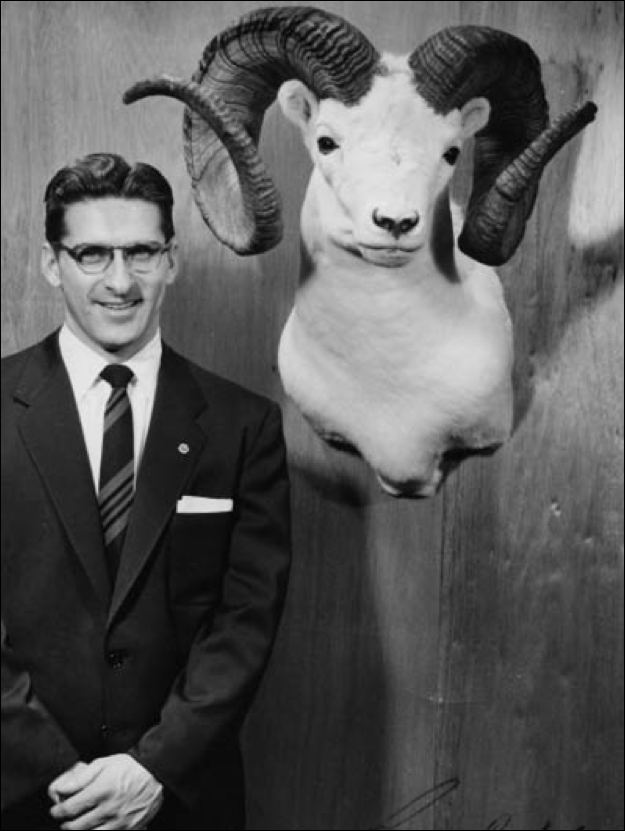

The slope where he died was so steep we couldn’t cape him out there, so we dug a shallow trench across the shale and dragged him to a narrow shelf. When we put the tape on him it showed his right horn to be 49-1/2 inches long, the longest ever recorded on a Dall’s sheep. My heart skipped a couple of beats. This could be a new world record head.

We caped the two sheep, loaded our packboards, and headed for camp. The horns of my ram, I learned later, weighed 27 pounds, and with my gun and other paraphernalia I was carrying close to 70 pounds. It was a long hard trip across the shale, off that mountain and up another to camp, and when we finally plodded in shortly before dark, we had a tough 16-hour day behind us. But I can’t recall a day that ever paid more handsome dividends.

Wally had a steaming-hot supper ready for us, but when we showed our trophies, everybody forgot about eating for a few minutes. After a short meeting of the mutual admiration society, we sat down and licked our plates clean.

Next day the three of us hiked back for the meat. It was on that trip that we witnessed one of the rarest sights I’d ever seen, a battle between a three-quarter curl ram and a bald eagle. The eagle came close to winning, too. The ram had crossed a ridge above us and started over a shale slide where no man would have dared to venture. The eagle appeared out of nowhere and dived on him like a jet. The sheep all but lost his footing on the slippery shale, a fall which would have meant certain death, but he recovered and ducked for shelter under a nearby ledge with incredible speed and agility. He rested there while the eagle circled overhead.

Finally the sheep made a dash across the slope for the safety of a ravine. The eagle swooped down on him a couple of times, but couldn’t get at him. This encounter proved something I’d long suspected, that eagles do sometimes prey on sheep, even full-grown ones.

The weather cleared and Jack Lee flew in to return us to Anchorage on August 25. We hurried to get our heads measured by experts. I was especially eager, for I knew I had a very unusual ram.

It turned out that all three of us had killed record-class Dall’s rams. Entered in Boone and Crockett Club competition, Wally’s scored 163-6/8 points, very good for a first sheep, as he remarked with a satisfied grin. Frenchy’s went a little better, with 164-4/8 points, and I had done better still.

When Harry Swank and Capt. Louis Yearout, official Boone and Crockett measurers, taped my trophy they indicated a firm belief that I’d taken a new world-record sheep. But that still didn’t make it official. I shipped the horns to B&C headquarters in New York, and the days dragged by while I chewed my nails and waited for the final word. Finally, on October 25, two months to the day after we got home, a wire from Mrs. Grancel Fitz, the record committee’s secretary: “Congratulations on your new world’s record Dall’s sheep.”

I guess I was the happiest hunter on earth, and a lot of other Alaska sportsmen were pleased too. I’d taken the best white sheep head ever collected, and Alaska had finally copped top honors from the Yukon Territory. The previous record, which had stood since 1948, was a ram that scored 182-2/8 killed near Champagne by Dr. Earl J. Thee.

Our hunt had proved what I’d believed for two or three years, that the biggest Dall’s ram alive would be found in the remote, high pastures of the Chugach Range. Is there another up there even bigger? Only time will tell, but I mean to go back and have a look every now and then.

Story originally appeared in the October 1957 issue of Outdoor Life.

Reprinted with permission of Craig Cook, Frank’s son and current owner of the ram.

Witness the hard-core determination of North America’s most successful hunters. They combined physical conditioning with research, fair-chase ethics, and shooting prowess to seek out and harvest legendary trophy animals.

Thirty hunters. Thirty record-book trophy big game animals, most of them taken without guides on public lands. Thirty epic tales to share back at hunting camp. These are the real-world stories behind some of the top-scoring trophies ever recognized by the Boone and Crockett Club.