August 2. – We rose late, to find the sun brightly shining. Rungius soon started to look at his caribou carcass; Osgood and Gage went to get the meat of Osgood’s ram. I stood near the fire for a few moments after they had left, and was gazing at the high mountains three miles or more distant, east of the north branch of Coal Creek, where I intended to hunt, when I saw up near the top what appeared to be sheep—whitish spots against the dark background of the slope. My glasses showed six sheep, not clearly visible, but looking like rams.

It was a little after mid-day, and in five minutes I had started down the creek flushing ptarmigan and disturbing ground-squirrels on the way, while red spruce squirrels scampered and frisked about. After passing rapidly along the well-beaten moose trail until near the forks, I again looked through the glasses. Yes, they were rams, nine in all, apparently, with fair horns, and the horns of one, which was feeding to the right a short distance from the others, seemed to be particularly large.

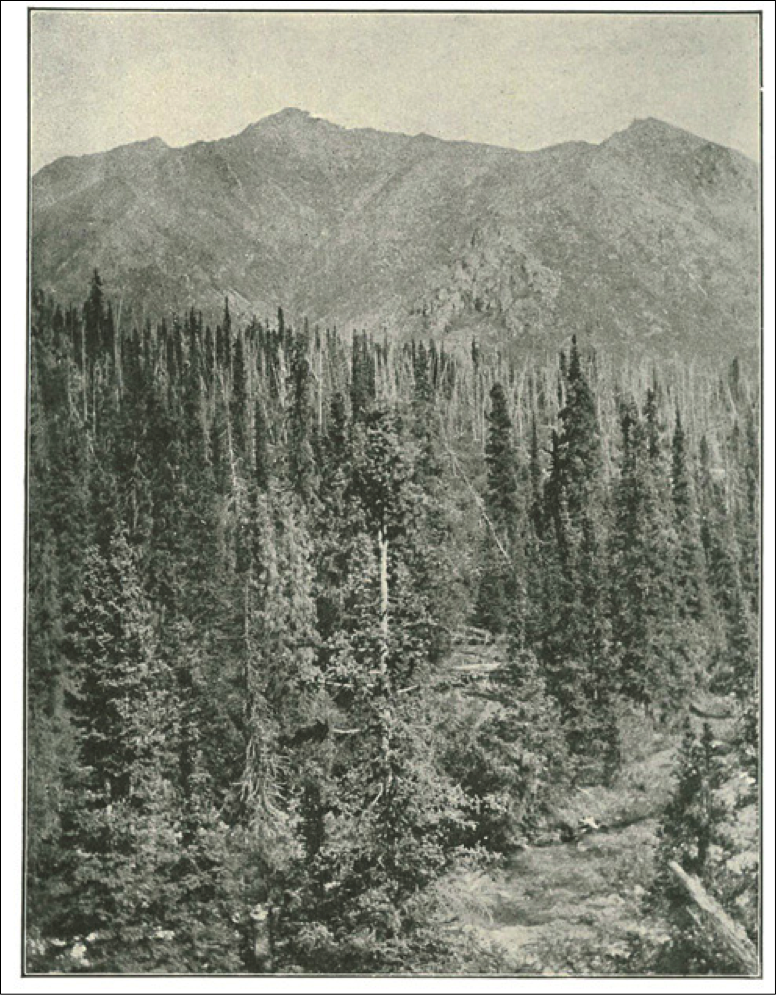

They were on the west face of a high, rugged mountain, about a mile broad, with very steep, green slopes extending from the creek directly up to near the crest, ending against shagged precipices, pinnacled above by high peaks of limestone and iron-stained rock which, under the sunlight, displayed a wonderful harmony of colors—red, black, and white. The slope was furrowed by three ravines, and through the bottom of each fell brooks, dashing and leaping over the rocks of the sharp decline. From a distance these ravines looked like deep concave depressions, giving a wavy appearance to the broad mountain face.

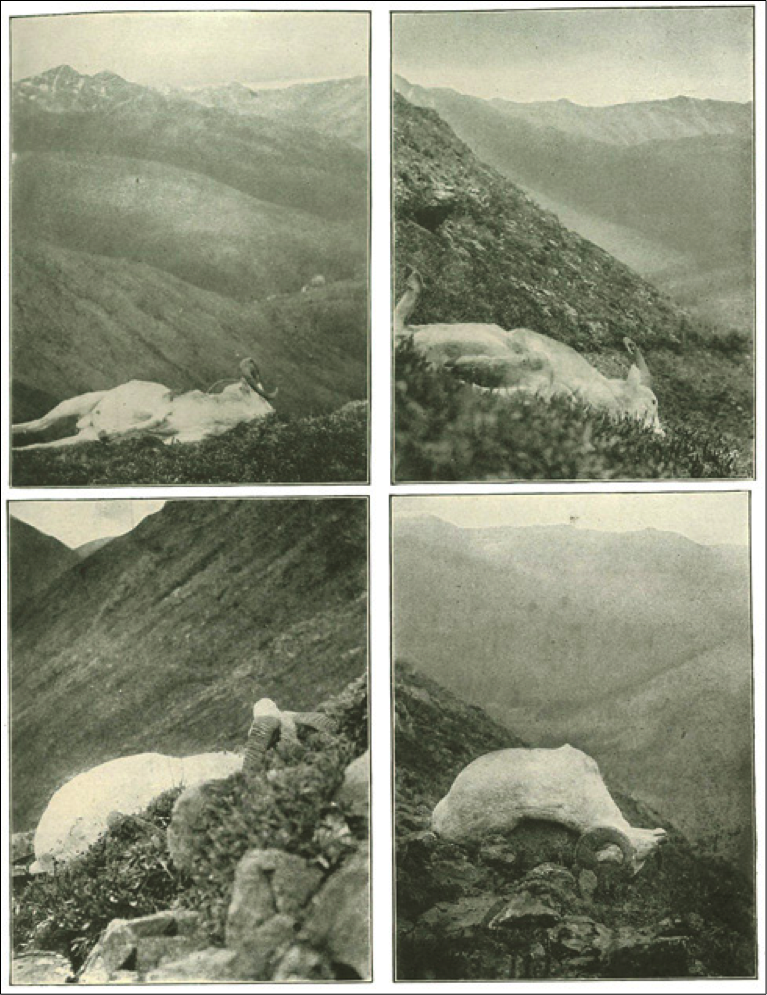

They were on the west face of a high rugged mountain, August 2.

Three of the rams, including the one with big horns, were feeding in the middle ravine; the other six were standing on the edge of the next one, which was so precipitous that it was more like a deep cañon on the mountain side. In studying an approach, it appeared to be quite possible to climb out of sight in the ravine to the right, but should the rams in the meanwhile feed in that direction, they would surely see me. Though it required more time, I decided to pass clear around the mountain, and by winding up the south-east side come in sight above them, thus avoiding any possibility of their seeing me unless they should go back over the crest, which for the next few hours was unlikely.

I waded the creek, circled, and began the ascent through the timber, where were rabbits and spruce grouse, not observed nearer to the divide. Coming out on the south side and circling upward, I not only found it very steep, but it was extremely difficult to force my way through the dense growth of dwarf birch which covered the lower slopes of the south exposure. But gradually winding upward I reached a point high above the sheep, where the ground was so rough and steep that it was difficult to work among the crags and rocks to the part of the crest that I had marked from below as directly above the sheep. The slope now became so dangerous that it was necessary to sling my rifle on my back, so that I could use both hands. At length, I stood at the marked point, just below the crest, and paused awhile to rest and recover my breath after the exertion of the climb.

After a few moments I slowly crawled forward and looked over. A hundred and fifty yards below me was the large ram, lying down near the edge of the second ravine, and a little to the left below it the heads of two smaller ones were just visible. The wind was fresh and fairly strong, blowing directly from me to them. As no other sheep were in sight I concluded that the rest were below in the ravine. The ram was peacefully looking down on that wondrous landscape, without suspicion of danger from above. Sitting with elbows squarely on my knees, I fired at the centre of its body. I heard the bullet strike him before he rose with a jump and stepped forward, quickly passing out of sight over the edge of the ravine. The two smaller rams sprang to a standing position, and looked sideways and down, apparently not much alarmed. None of the others appeared while I remained stretched at full length, motionless, for ten minutes. The big ram then suddenly staggered in sight again on the edge of the ravine and I aimed, fired, and the bullet struck him in such a way that I was confident he had been killed as he dropped back into the cañon. The two small rams slowly followed him.

Then as quickly and as noiselessly as possible, I walked two hundred yards to the right, just below and parallel with the crest, to a point where I could look down in the cañon. Seventy-five yards away on the opposite side and a little below were eight rams closely bunched, all nervously looking down. They had heard the noise of the old ram falling and were looking in that direction. They had not determined the direction of the danger. I quickly selected the one with the largest horns and off-hand shot him through the heart. The rest jumped and ran a hundred yards downward, and rushed up the broken surface to the edge of the cañon directly below me, where all stopped and looked about in excitement, not yet having seen me.

Selecting the one with the next largest horns I sent a bullet through his heart, and he dropped in his tracks. The others scattered, ran about a little, and stood again, still not having seen me. Selecting the grayest I shot him through the middle of the body. He ran down the cañon slope near the second dead ram, and stood a moment until another shot killed him. The rest, three of which had good horns, bunched, ran a few yards, and again stood and looked up, for the first time seeing me. In alert attitudes they gazed at me for several seconds until I moved, then all dashed across the slope and disappeared through the ravine, again coming in sight for a moment before they rushed around to the other side of the mountain. I went quickly down to the third ram on the edge of the cañon and sat down to smoke my pipe.

After the excitement of the hunt the vast panorama of mountains about me never seemed so beautiful. Directly below were the bare, steep slopes extending to the timber which bordered the creek. Beyond, lay the valley of the west fork, fringed green by the spruces, while the waters of the creek were shining and glistening in the rays of the setting sun, which tinted with gold the heavy clouds on the horizon. The lofty mountain behind camp stood out boldly, its high-turreted rocks and rough peaks forming fantastic shapes against the skyline, and at its base our camp fire burned brightly. Behind, stretching far away, were the bewildering masses of the main Ogilvie ranges, the varied rocks blending their colors and fading like a wavy ocean merging into the soft, dull blue of the sky beyond. A large ram lay at my feet; below in the cañon was another; above on opposite sides of the leaping stream two more, my final success. Still with me is the vivid memory of those wild sheep rushing across the rocky slope in that wonderful landscape.

After photographing the dead ram near me I began to take off the skin of his head and neck. The clouds gathered fast and it soon began to rain. After cutting off the head I carried it with the skin down into the cañon and then went up to the third ram killed which was very gray, and was selected to represent the “Fannin” type for the collection of the Biological Survey. After photographing him I gralloched him and left him for Osgood to preserve. Then crossing the stream to the second ram killed, which had fallen on an exceedingly steep slope, I photographed him also and removed his skin and head. Both were carried to the ram below, the first one killed. Up to this time I had not been near him and the climax of the day came as I saw lying before me an enormous ram of grayish color, grizzled with age, his large, perfect horns sweeping upward in spirals extending well above the eyes, a finer trophy than I had ever anticipated, an old veteran of the crags and peaks. It was raining heavily, the mountain crests were covered with clouds, and a dense fog was settling all around me. I tried several exposures for photographs, and measured the ram whose length was fifty-nine inches. In the rain and cold I finished skinning him at 10:30 P. M. The head was cut off and left in the skin.

Thoroughly soaked, I rested for awhile and ate a couple of crackers. Far below in the distance the campfires could be seen glimmering through the fog, which soon became so dense that the darkness increased. The nights were now perceptibly darker, so much so that in this heavy fog I could not clearly see the ground. Tying the larger head and skin in my rucksack, also putting another on my back, and taking the third in my hand, I began the descent. The first hundred feet proved the impossibility of going on without lightening the load; so the smaller head and skin were left on a rock at the bottom of the cañon. Then another start was made with the remaining pack rearranged and with the rifle slung on my back. The descent was so steep and the cañon so dark that it was necessary to climb to the slope above and zigzag slowly downward. I was unable to see the surface of the ground and advanced slowly, feeling each step, falling several times, continually stopping to rest and rearrange the pack and the head. Gradually I worked down to timber-line where, though it was darker, the footing was smoother, and finally I reached the creek. It had required two and a half hours to make a descent of less than two miles.

Fording and refording, now resting, now fixing the pack, I kept on in the rain. As daylight returned it became easier to travel and I reached camp at 4 A. M. A fire was soon started; some food and tea taken; then repose, and my pipe; after which strength returned and I slept.

We had succeeded in the main object of the trip, which was to obtain good specimens of the sheep of that region. None were so dark as the so-called Fannin sheep, but some were good representatives of the white Dall sheep, except the color of the tails, which in all of them was black. Probably half the sheep in this locality faintly displayed the pattern of the Fannin sheep, but all were nearer the color of the other. (* See appendix for descriptions of the types; also see plate in Chapter XX.) It is worth recording that all the sheep seen in the first band of rams had the widely spread type of horns; all in this second band had the narrow type.

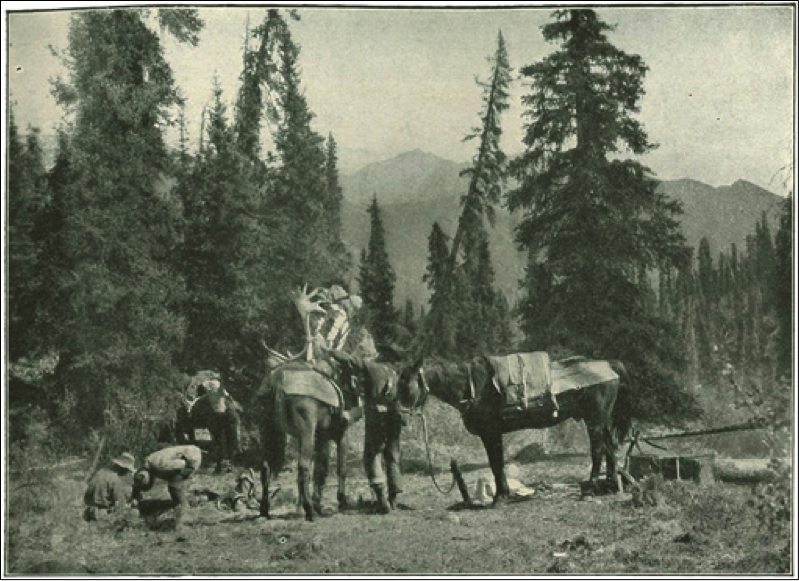

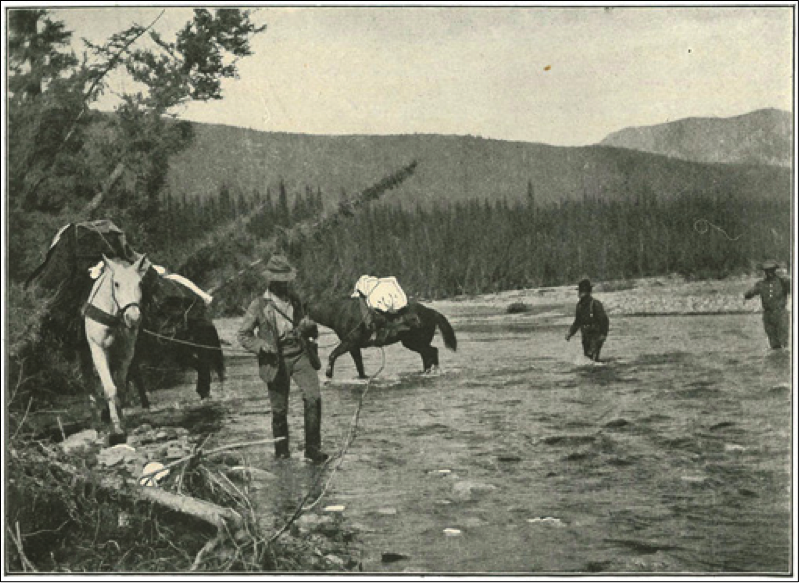

Breaking the hunting camp. (Photograph by W. H. Osgood.)

Breaking the hunting camp. (Photograph by W. H. Osgood.)

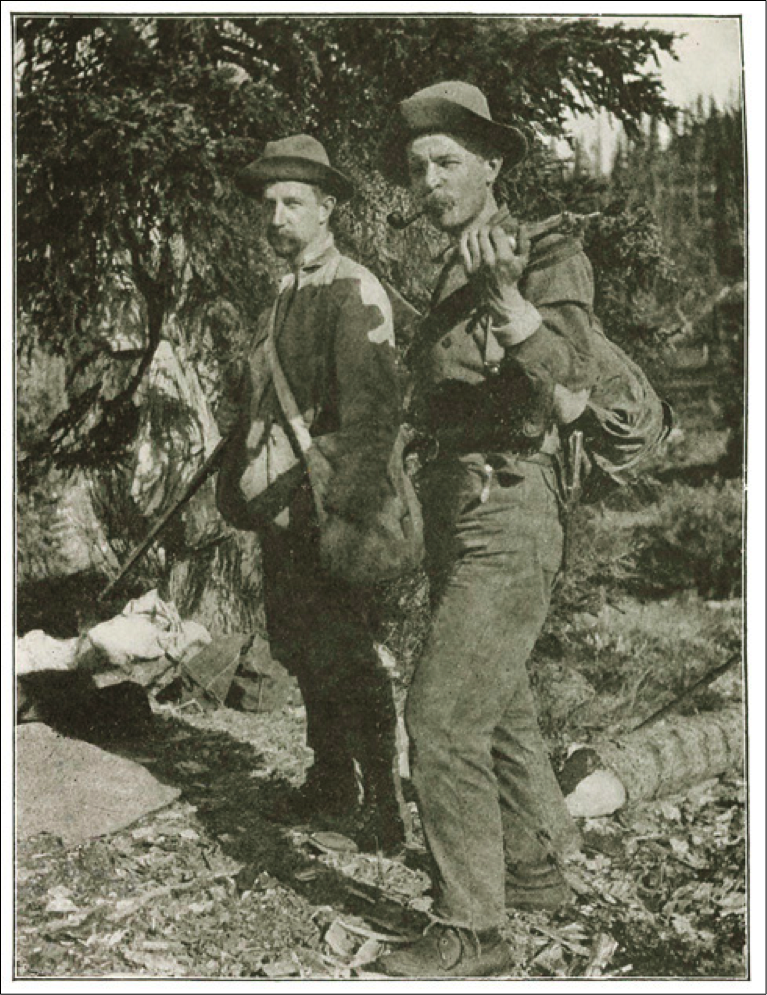

August 3-6. – The next three days were spent in camp, except that short trips were made by Rungius and Osgood to bring back the meat and remaining skins, to gather the traps and make local sketches. Rungius sketched the heads of my sheep in the flesh, after which I prepared them and spent the time arranging and drying them. The fourth day I went down the creek and up the branch that enters below the forks, on the chance of finding a bear, but saw nothing, and returned after an interesting tramp among the mountains.

August 7 was spent in breaking camp, shoeing the horses, and making up the packs. Osgood had collected one hundred and ten specimens of small mammals and birds, besides the larger game. We slept for the last time in that delightful camp, and the next morning packed and started. The return was rapid as compared with the trip up river. It was all down grade; we knew the route; the trail had been cut; the loads were lighter, only that of the caribou horns being bulky and awkward. There were numerous salmon in the river; bear tracks, those of the black bear only, were more plentiful, and a few fresh moose tracks were seen. On the afternoon of August 11 we reached the Yukon River.

Long before leaving Coal Creek a steamer whistle reminded us of civilization. Our exact travelling time from camp at the head of Coal Creek to the Yukon River, deducting all stops of over five minutes, was twenty-one hours and four minutes. We forded Coal Creek fifty-eight times. While in the hunting country it had rained eight days, but only twice did fog and rain prevent reasonable hunting. Twenty-seven days were clear, and at no time was there a very strong wind.

A steamer was being loaded with coal at the chutes, but owing to their faulty construction three days were required to load a barge; therefore we were obliged to endure the delay. We boarded the steamer August 14, and the following afternoon arrived in Dawson, where everything was packed and sent to Washington.

You’ll be pleasantly surprised by the high-quality photographs and drawings from decades long gone that are scattered throughout these titles. This series includes books by renowned adventure authors such as Theodore Roosevelt, William T. Hornaday, Charles Sheldon, and Frederick C. Selous, to mention only a few. Available online at:

www.historyofhunting.com

www.boone-crockett.org