Sagamore Hill Award-winning trophies are broadly represented throughout this book. After all, the award was originally given for the highest-scoring antlers, horns, or skull of a given species recorded under the Boone and Crockett Club’s measurement system and rules of fair chase at the time of the award; by definition, representative of the foundational elements of this book’s stories.

The formulation and codification of the current version of the B&C big game scoring system came together in the middle of the 20th century, adopted in 1950, with the first publication based on (and outlining) the new methodology being the 1952 edition of Records of North American Big Game. The previously titled Big Game Competitions (now called Big Game Awards Programs) initiated in 1947 and held annually, began using the current version of the official measurement system starting in 1950.

This timeframe clearly overlapped with the development and initiation of the Sagamore Hill Award by the Roosevelt family. Notably, awards for the 1948 and 1949 competitions were made before the current scoring system was adopted. They were awarded based on the selection by a Judges Panel. So, prior to that time, the Club’s records-keeping efforts were largely represented by the National Collection of Heads and Horns and earlier scoring systems. The first scoring systems, initially developed starting in 1902, were comparatively primitive and uncomplicated but formed the basis used in compiling the first two editions (published in 1932 and 1939, respectively) of Records of North American Big Game.

In essence, early award-winning trophies were being added to the records at something we’ll refer to here as a second inflection point in time for the Club’s work. The first inflection point, some 50 years earlier, had resulted in the creation and inception of the Boone and Crockett Club at a time when the ultimate extinction of our native big game and many other species was considered a frightening but viable possibility. President Theodore Roosevelt’s calls to action, in conjunction with a number of his forward-thinking and highly-capable colleagues, set in motion the institution, its core principles, and the early policies which continue to drive and guide us today.

During this second inflection point, the Club began collecting and recording records of North American big-game trophies. In addition, the early fruits of the North American Model of Wildlife Conservation began to emerge. Many big game trophies taken in earlier times were still being discovered, measured and entered into the records at the same time that an increase in the number of more recently harvested record specimens began to take off.

The formerly listed R.C. Bentzen’s typical American elk (1950 award, now listed as hunter unknown) and Edison Pillmore typical mule deer (1953 award) represent examples of such early Sagamore Hill Award winners—trophies presented predominantly on the merits of scores relative to other high-ranking trophies of their (and all the other) species listed in the B&C records. Not surprisingly, Sagamore Hill Medals tended to be given to the hunters of new World’s Records. Unfortunately, stories of these early award-winning hunts were not necessarily recorded in great detail. Further, the hunt details were not as likely to have been as fully scrutinized in the same way, especially given the even higher ethical hunting standards emblematic of the Sagamore Hill Medals bestowed in later years.

Most award winners in those early competitions largely represented the single-most outstanding trophy presented at the event, and therefore, not selected based on as many beyond-the-score factors as they are today. Developments in transportation and technology, among other considerations, prompted an evolution in the concept of fair chase and ethical hunting practices. As a result, the number of new requirements listed on the entry affidavit and hunt information forms have increased substantially over time.

Over the last two decades. New fair chase rules based on changing hunting equipment, methods, and other factors have increased the criteria scrutinized when considering a specific trophy for an award nomination. Although new World’s Record trophies are still likely to be considered potential award winners today, not all hunters of a new top-scoring trophy are likely to receive the award based on the merits of high score/high rank and fair chase alone. As articulated in the 12th edition of Records of North American Big Game:

To be eligible for nomination, the trophy must either be a new World’s Record or one that is close to it. In addition, the hunt that produced the trophy should be exemplary of those characteristics most highly valued by Roosevelt: fair chase, self-reliance, perseverance, intentional selective hunting, and mastery of challenges being some of those. After reviewing the hunt accounts of possible candidates, the Judges Panel may choose to nominate a particular trophy for the Sagamore Hill Award. The nomination is reviewed by the Big Game Records Committee Chair who may choose to make further investigations before recommending the award to the Club.

Supporting the results of these evolved considerations, only four Sagamore Hill Medals have been awarded over the past 24 years, even though many more new World’s Record and top trophies have been added to the records books. In essence, a very high bar has been re-set, and as such it remains one worthy of the original goals of the Club.

Even though the stories behind the award winners were not all recorded well or were necessarily epic in the sense of all-in adventure, hardship, etc., they have nevertheless stood the test of time as truly outstanding representatives of their big game species. As a testament to their individual merits, all but three of the 17 Sagamore Hill Award winners remain to this day in the top five ranks for their species in the All-time records. The remaining three are the only exceptions to a top-10 or top-25 records book rank: the Mercer typical American elk—a top-10 trophy (ranked No. 9 at this printing); the Reeve Alaska brown bear (ranked 30th in a five-way tie); and the Pillmore typical mule deer (ranked 132nd in a seven-way tie at this printing). In the end, no one can deny that they are all truly representative of the best examples of their wild and free-roaming species!

Most of the 17 B&C award-winners to date have at least some recorded hunt story to them. Many of these are included in this book as standalone stories. Some of the remaining stories are included within this chapter.

- Robert C. Reeve, Alaska Brown Bear (1948)

- E.C. Haase Rocky Mountain Goat (1949)

- R.C. Bentzen/hunter unknown, Wapiti (1950)

- Edison A. Pillmore, Mule Deer (1953)

These nine Sagamore Hill Award winners, some of which lack hunt details, are nevertheless enriched by the contents of the B&C Club’s records files and other sources of hunter details. All have been included to some degree in the pages that follow.

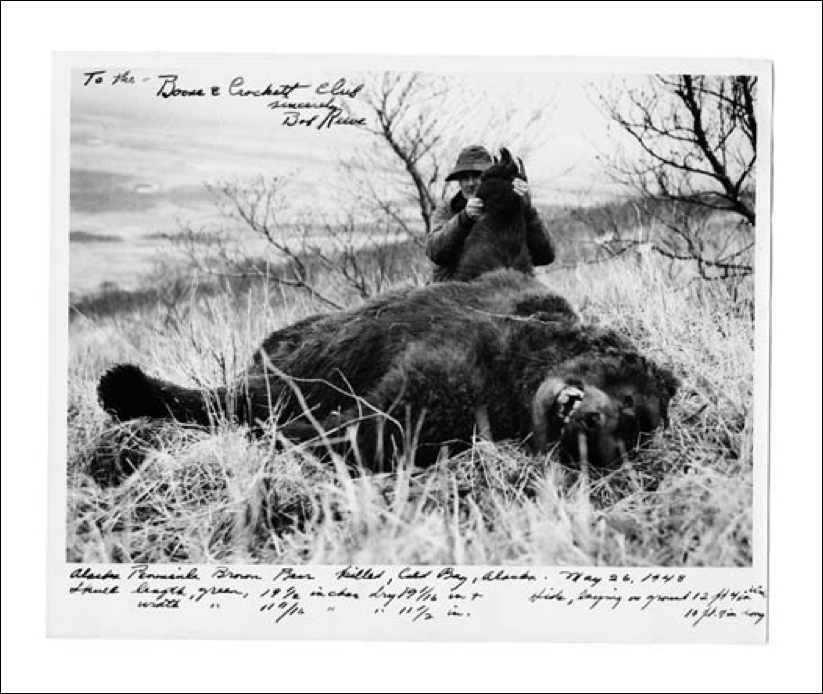

1948 Sagamore Hill Medal – Robert C.

Reeve Alaska Brown Bear – 29-13/16

Details of Robert C. Reeve’s 1948 Alaska brown bear hunt are quite thin, but fortunately, epic-quality bear statistics and one photo in particular lend weight to the merits of his outstanding trophy. Given Reeve’s background and extensive accomplishments—including landing planes on glaciers (the book Glacier Pilot, by Beth Day, was based on his story)—one has to consider that the hunt itself may have paled in comparison to the man’s day-to-day life adventures!

Reeve moved to Alaska in 1932 with no plane and no money. However, he had fairly extensive experience as an aircraft mechanic and pilot, and carved his niche in the world as a pioneering Alaska pilot. Between bush flights and gold mine supply runs, he logged some 2,000 glacier landings. After World War II, he founded and operated Reeve Aleutian Airways, an airmail, passenger, and freight delivery service to the Aleutian Islands. In all, he logged some 14,000 hours of flying time during his life.

In a correspondence with the Club, through Dr. Harold E. Anthony at the American Museum of Natural History in New York City, Reeve enthusiastically accepted the invitation to attend and receive recognition for his bear at the 1948 North American Big Game Competition. In addition, he requested that several of his hunting colleagues, including a major general and two lieutenant generals of the Air Force be included as guests, along with Reeve and his wife. Reeve later confirmed his four guests and sent along a check in the amount of $16 to cover their costs for attending the event. He also crated and shipped the bear’s hide to be present at the competition’s awards presentation.

From Reeve’s letter dated January 3:

It is my desire to contribute as much as possible to the success of the 1948 Competition. The hide of my record bear, now tanned and made up with a full head, is without a doubt the finest specimen of brown bear that has ever been killed. It is perfectly furred and processed, and in spite of shrinkage in drying and tanning, is still 10 feet wide and 9 feet long. Should the committee feel that they would like to include this bear in the public exhibition, I should be pleased to ship this rug to New York to arrive before January 19th.

We also have 1600 feet of color film of our last hunt showing about 50 brownies, include the actual stalking and shooting of my large brownie, and several others. I am bringing them with me and will be available for such private showings to the Club Members as may be desired.

Letters from Samuel Webb, later chair of the Records Committee, are included in the Reeve bear’s file in the B&C Records archives. In one, Webb wrote, very politely and “politically correctly” (especially for the times): “You will note that there is also a photographic competition but if you send in your movies of the bear hunt, may I suggest that you do not show the sequence of the bear actually being killed. Photos, before and after, are always extremely interesting but a lot of discussion results when hunters show the actual kill.”

Although the Alaska Department of Fish & Game brown bear fact sheet notes that a large coastal male brown bear may weigh up to 1,500 pounds, Reeve claimed his bear weighed some 1,800 pounds. In an article from The Seattle Times dated January 29, 1949, we note the following excerpt: “The flyer-sportsman, head of the firm which delivers air mail to the Aleutians, said he shot the bear May 26 near Cold Bay, at the tip of the Alaskan Peninsula, soon after the beast had emerged from hibernation—hungry and mean. Had it been shot near the end of its normal salmon-eating season, Reeve estimated it would have weighed about 2,200 pounds.”

In addition, written below the photo of the hunter with the bear, Reeve noted the hide, lying on the ground, measured 12 feet, 4 inches wide, and 10 feet, 4 inches long. These measurements, plus the following details, and the type of rifle Reeve used, are noted in The Seattle Times article as well: “Shoulder height of Reeve’s bear was 5 feet 4 inches, and it measured more than 12 feet standing erect. It was killed with a Model 96 Winchester.”

Should the measurements above be reasonably accurate, this was indeed a giant. For the records book, however, there are very good reasons that hides and weights are not included. Hides can very easily be badly mis-measured or stretched at the kill site, or before/after tanning. Weights, especially those of very large animals in remote places, would be nearly impossible to measure accurately, let alone consistently.

We’ll never know with certainty the actual live weight or dimensions of Reeve’s bear. However, between his piloting and cargo experience, and the equipment he may have had at his disposal (most likely at the nearest aircraft facilities), his measurements could have some validity. In any event—a huge bear! With final skull measurements of 29-13/16, Reeve’s brown bear (ranked in a five-way tie for 30th at this printing) is 15/16 of an inch smaller than the current World’s Record score of 30-12/16 inches.

Reeve was not only the accomplished aviator and Sagamore Hill Medal winner, but he later became a Regular Member of the Boone and Crockett Club. He also donated his award-winning bear trophy to the American Museum of Natural History.

Official Measurer’s Note: Just plain large! As bear skulls are scored based on length and width measurements, top-ranking Alaska brown bears range up to 1-½ inches longer or just over 1-¼ inches wider than Reeve’s trophy.

1949 Sagamore Hill Medal – E.C. Haase

Rocky Mountain Goat – 56-6/8

In addition to an archival photo (shown at right) from the 1949 competition and awards display, we are fortunate to have the following recap of E.C. Haase’s hunt from Grancel and Betty Fitz, written in the 1964 edition of Records of North American Big Game:

The fates also smiled on E.C. Haase, for his world-record Mountain Goat was the first he encountered on his first morning of climbing with Allen Fletcher, his guide. Packing out from Smithers, B.C., on September 15, 1949, their camp was made in the Babine Mountains. The huge solitary billy was spotted at about three hundred yards in the usual precipitous country, but it disappeared before a shot could be fired. When they saw it again, a few minutes later, the range had stretched to nearly four hundred yards, with no way to get closer. Mr. Haase, shooting prone with a .30-06, killed it with his third shot, and although it fell off the ledge and rolled down the mountain several hundred feet, it lodged in a snowbank with its horns undamaged.

The hunt location is listed in the records as the Babine Mountains, British Columbia, Canada. Other than these tidbits and a photo of the mount, there appears to be very little additional information available on Haase’s Rocky Mountain goat, or Mr. Haase himself. That said, Mr. Haase’s trophy is currently owned by the Boone and Crockett Club’s National Collection of Heads and Horns. It remains tied for the No. 2 position at 56-6/8 B&C points in the All-time records for Rocky Mountain goat. Haase’s goat shares that position with Gernot Wober and L. Michalchuk’s 2001 Sagamore Hill Award-winning goat.

Official Measurer’s Note: Rocky Mountain goat horns don’t offer a tremendous range of measurement stats, but Mr. Haase’s trophy demonstrates both great length (12 inches even on each side, whereas the single-longest horn measurement in Trophy Search is 12-4/8 inches) and circumference measurements (6-4/8 inches for Haase’s goat versus the highest top measurement of 6-6/8 inches found in Trophy Search). Only this billy’s tip-to-tip spread measurement is significantly less than the most extreme example in the records—9 inches for the Haase goat, and the widest recorded spread is 13-2/8 inches. However, spread does not factor into the overall score calculation for goats.

1950 Sagamore Hill Medal – Dr. R.C. Bentzen

Wapiti – 441-6/8

The Sagamore Hill Award presented to Dr. R.C. Bentzen for a wapiti (American elk) in 1950 was later listed and properly classified as hunter unknown. In the chapter, “Some Stories Behind the Records,” by Grancel Fitz and included in the 1958 edition of Records of North American Big Game, Fitz wrote:

Not much is known about the record Wapiti except that it came from the Big Horn Mountains of Wyoming, as far back as 1890. Nobody knows who shot it. Discovered by Dr. Bentzen in a barn, and remounted with a new cape, it can still claim a comfortable margin of more than 27 score points over its closest modern rival. The natural winter ranges of the Wapiti herds have been settled up since this gigantic specimen was taken. As the Wyoming bulls now have less favorable forage in the crucial time when they begin to grow their new antlers, this one may stand for many more years.

Sadly, the actual hunter’s name and story are not known, but this magnificent trophy bull’s antlers stand on their own and still rank in the No. 3 position in the All-time Boone and Crockett records for typical American elk. It is the only picked-up trophy to have ever received the Sagamore Hill Medal. This exceptional trophy is owned by the Jackson Hole Museum.

Official Measurer’s Note: Folks viewing trophy bull elk (especially typicals) may say they all look the same. Yes, but… the longest single point on a bull can (per Trophy Search) range up to a whopping 30-7/8 inches, greatest circumference measurements to 14-4/8 inches, greatest spread up to 63-3/8 inches and longest main beam as much as 66-3/8 inches. From each individual bull to the next, conformation differences can create a wide range of total score outcomes based on the combination of these factors. In the case of this bull specifically, it is the second-highest scoring 8×7 (points on right antler and left antler, respectively) in the B&C records. Further, exceptional beam length and symmetry—61-6/8 inches (right) and 61-2/8 inches (left)—and a longest point of 26-6/8 inches lend to its high overall B&C score.

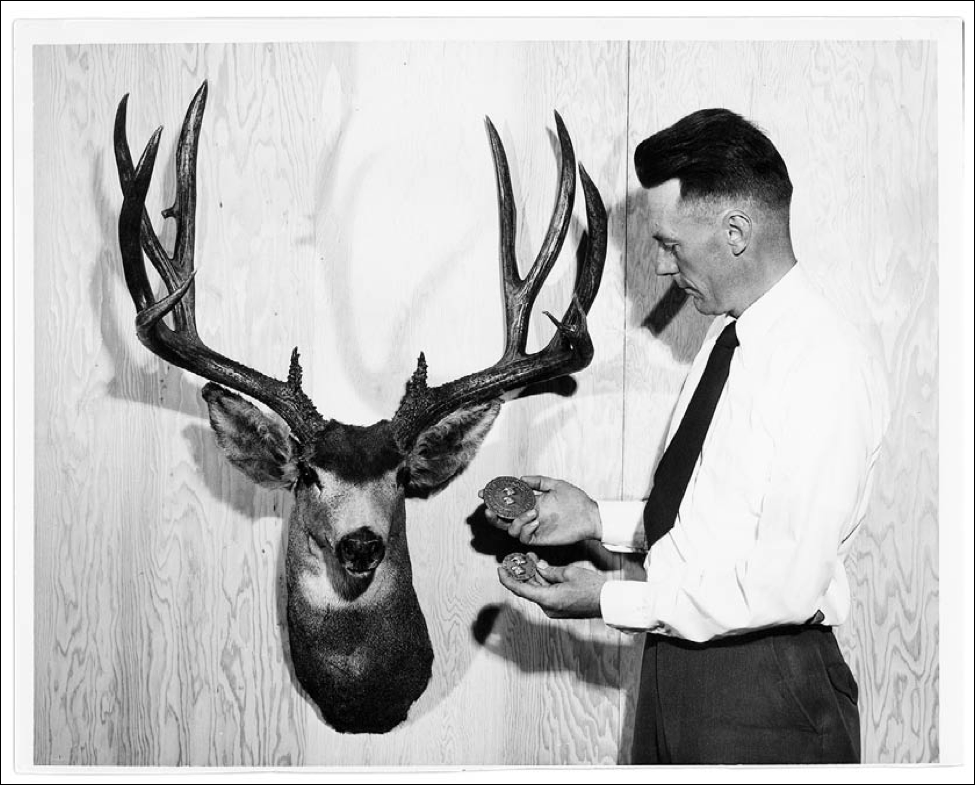

1953 Sagamore Hill Medal – Edison Pillmore

Mule Deer – 203-7/8

Sadly, there is virtually no information related to Edison Pillmore’s hunt for his then-record typical mule deer.

An article from the Greeley Daily Tribune (Greeley, Colorado), dated Friday March 26, 1954, indicates that Pillmore’s trophy was taken in the Jackson County, Colorado, area in 1949. Mr. Pillmore died before entering the head. His widow later submitted it for the records.

However, as Granzel Fitz wrote in the 1958 edition of Records of North American Big Game, we have a glimpse into the evolution of the category in terms of the number of trophy typical mule deer submitted for entry into the records, especially early on:

Our new Mule Deer lists offer a close parallel in that the Typical record-holder is a comparatively recent head, while the Non-Typical leader is another old trophy with an obscure background. The reason, of course, is that nobody used to think of records unless the rack of antlers carried an exceptional number of points. A lot of the finest old Non-typical heads were treasured and preserved, while many fine Typical racks have been lost. The world record Typical head in the 1952 book was an old-time trophy that still has a larger basic structure than any Mule Deer rack ever measured, so we have reason to think that more new records in this case are likely to turn up.

That champion in the 1952 lists carried four big abnormal points which totaled 24-7/8 inches in length. The resulting penalty brought the score down to 200-3/8, and this made it vulnerable. In the 1953 North American Big Game Competition, the late Edison Pillmore’s trophy, from Jackson County, Colorado, raised the standard to 203-7/8. Then, in the 1954-55 Competition, the present world record was established when Horace T. Fowler’s specimen was scored at 208-6/8. It is unfortunate that no other information on this one could be obtained, beyond the report that Mr. Fowler shot it in the North Kaibab country of Arizona in 1938. The same show, by the way, brought in other heads scoring 203-4/8, 201, and 200-3/8, which meant that the 1952 record-holder would have fared no better than a fourth-place tie.

Many outstanding typical mule deer have been added to B&C’s records since Mr. Pillmore’s trophy was entered and honored. As a singular specimen, it has fared the least well of the Sagamore Hill Medal winners in terms of the All-time rankings. Today, Pillmore’s trophy ranks 132nd in a seven-way tie at 203-7/8. That said, it is with reasonable certainty that no one would turn down an opportunity for a buck like this!

Official Measurer’s Note: Not surprisingly, this typical mule deer trophy possesses all the characteristics of a top-scoring buck—including modest asymmetrical aspects common to most natural antlers. A gross typical score of 213-1/8 nets significantly lower (9-2/8 points total) due to 3-3/8 inches of non-typical “character” points, including an extra point on the end of the left main beam, making it look like an open-end wrench, and a sticker point off the G2 on the deer’s right antler. Otherwise, modest deductions came from side-to-side main beam, G3 and G4 asymmetry. Matching 3-inch brow tines (G1s) and most circumference measurements over 5 inches round out this fine buck’s impressive antler frame.

Witness the hard-core determination of North America’s most successful hunters. They combined physical conditioning with research, fair-chase ethics, and shooting prowess to seek out and harvest legendary trophy animals.

Thirty hunters. Thirty record-book trophy big game animals, most of them taken without guides on public lands. Thirty epic tales to share back at hunting camp. These are the real-world stories behind some of the top-scoring trophies ever recognized by the Boone and Crockett Club.