Part I: The Sheep Hunter’s Dilemma

It was decision time. The four of us were hunkered down behind weathered, black boulders on a windy ridge gazing into a shallow basin with a small rivulet meandering down the middle of it. The bright Yukon summer sun shimmered on the water as it trickled from the snowpack above, down the valley and past eight white rams feeding on the green alpine below; four of them were full curl or better ranging from thirty-five to thirty-eight inches. It was the last afternoon of the last day of the last hunt of August. Tomorrow would be spent breaking camp, loading our heavy packs, and scrambling up a jumbled, unstable rockslide. After trudging over a snowy pass, we would settle down, tired and hungry, in the late evening, still a long day’s hike from our hunting vehicle. Would this be our last opportunity? How badly did we want these rams?

The ridge we had climbed sloped steadily upwards, rising sharply to join the rugged 7300-foot peak behind us. A well-used sheep trail worn into the rocks right beside us revealed the fact that this was a preferred escape route. These sheep would not be bedding down in the basin tonight. The sheep hunter’s dilemma was upon us. Should we wait, watch, and hope? Or try to make things happen?

“What would happen if we left the kids up here, circled way around and showed ourselves to the sheep from below? Maybe they’d mosey on up right past Jodi and Graeme,” my buddy Pete, suggested. “Isn’t that the mark of a good Yukon father, chasing sheep for his children?”

“As long as you leave me the gun,” his sixteen-year-old daughter, Jodi, insisted.

“So you’re going to expose yourselves at a distance. They’ll take one look at Pete’s hairy chest and run to the next mountain range,” my seventeen-year-old son Graeme remarked snidely. “Besides, isn’t that a little like trying to herd cats?”

He was right. Recalling past experiences, this strategy had never been very successful. When it comes to escape, sheep appear to be divergent thinkers given to leaps of logic that defy predictability. Indeed, stalking sheep is much like the elegant game of romance. The quarry is beautiful, fleet-footed, poised, intelligent, and most deserving. The stalk may be well thought-out, logical, and predictable, but therein lies the rub. If one is too obvious in the chase or tries to force the issue, the object of desire becomes unpredictable and anxious, changing into a creature with a wide array of baffling, sometimes contradictory, but very creative escape mechanisms.

It is the logical and predictable pursuing the erratic and elusive. The results, in retrospect, are often highly amusing, but in the moment or immediate aftermath, create considerable pain, self-doubt, feelings of inadequacy, and more than a little confusion.

Such is sheep hunting. As in life or romance, it is often better to wait, hope, and observe than run, pursue, and make things happen. What do you do, though, when time is of the essence?

Part II: The Day Before

Graeme and I were also still considering the previous day’s adventure. While Jodi and Pete had been scouting for rams on the mountain to the west, Graeme and I had spotted a heart-stopping, lone, long-horned ram with a tight curl and perfect tips flaring up and out, bedded down on the lee side of a saddle-back ridge that extended from the other side of the main peak we were camped under. Any successful approach from the front was deemed improbable, so we retreated out of sight and clambered on hands and bruised knees up the steep backside of the mountain.

After negotiating a lengthy circular route, keeping out of sight just under the highest ridges, we were ready to ambush the ram from behind. This took about seven hours of steady up-and-down meandering and found us in the early evening, five miles from camp on the saddle back quietly and carefully inching down the slope, taking a few steps crouched over, looking to both sides, slowly lifting our heads and scanning the many hidden hollows below us, hoping to see that first glimpse of white or the brown curl of a horn above a rock.

The breeze, a remnant of the heat of the day, was thankfully still in our faces, taking our scent up and away from our quarry. We struggled to maintain that delicate balance between excited anticipation and disciplined patience, well aware that in seven hours the ram had probably fed, moved, bedded down elsewhere, or was even now having his last feed of the day directly below us. Maneuvering to the point where the downward slope of the ridge opened up, we side-hilled cautiously, grimacing silently at the sound of loose shale shifting or dry patches of grass crunching under our hiking boots. No ram anywhere. After covering considerable barren ground, it was back to the top to ponder our circumstances and bolster our flagging energy and waning courage with bagels, cheese and chocolate bars.

It was after eight o’clock, the air was cooling rapidly, the shadows were lengthening, and the homing instinct was kicking in. We had a three-hour brisk walk which would lead us along the ridge to its lowest point, down a well-worn sheep trail into the valley, and up a rugged creek bed to a grassy pass. Then it was down and around to camp, comfort, companionship, and the smell of hot, salty soup with islands of greasy, sliced Mennonite farmer’s sausage floating on top promising to keep the arteries lubricated and the body warm all night. We had no idea where the ram had gone and our minds were fixated on getting back to camp.

This was a mistake.

At the low end of the ridge were a number of large, light-colored boulders. As I hurried onwards, I paid little attention to what was in plain sight, until Graeme hissed, “Dad, sheep!” One of the “boulders” had lifted its head and was looking right at us. It was our ram feeding in a green hollow between patches of red-tinted buck brush six hundred yards from us. Two hunters silhouetted against the receding sun were enough to convince him to leave for safer pastures. The ram was on the move. We watched as he followed the sheep trail down into the valley, through the creek and up the slope across from us. We scrambled to pull out the spotting scope, focused in on him, and took turns etching the look from behind in our memories: the big bases, and then on each side, those beautiful tips flaring up and out.

What a pretty ram. What a sinking feeling! We had blown it. How far would this ram go? The mountain he was going up was right behind our camp, but would he stay there or was he one of those old loners whose survival depended on being wary, skittish and spooky?

“Never stop hunting. We should have taken our time and glassed ahead,” I muttered.

“He must have had his head down right beside the buck brush. I looked that over just before he spooked and I never saw him,” replied Graeme.

“Man! We could have snuck down that gully and come up right behind him,” I said ruefully.

“This just means we’ll see a bigger one tomorrow, Dad. It’s happened before.”

The long walk back turned into a father/son mutual disappointment therapy session. It seemed to follow a predictable pattern – orally visualizing the ram’s worthy assets, the curve of his horns, the symmetry, and the tips going up and out. And then reference to our painful failure, the regret, ideas of what might have been, and eventually some laughter and a smidgen of hope that he hadn’t gone too far and that we might get another chance tomorrow.

Mostly, though, we were less than kind to ourselves for squandering a hard-earned opportunity by losing patience and focus at the last critical moment and appearing, to the ram at least, far too obvious in the chase.

Part III: The Plan

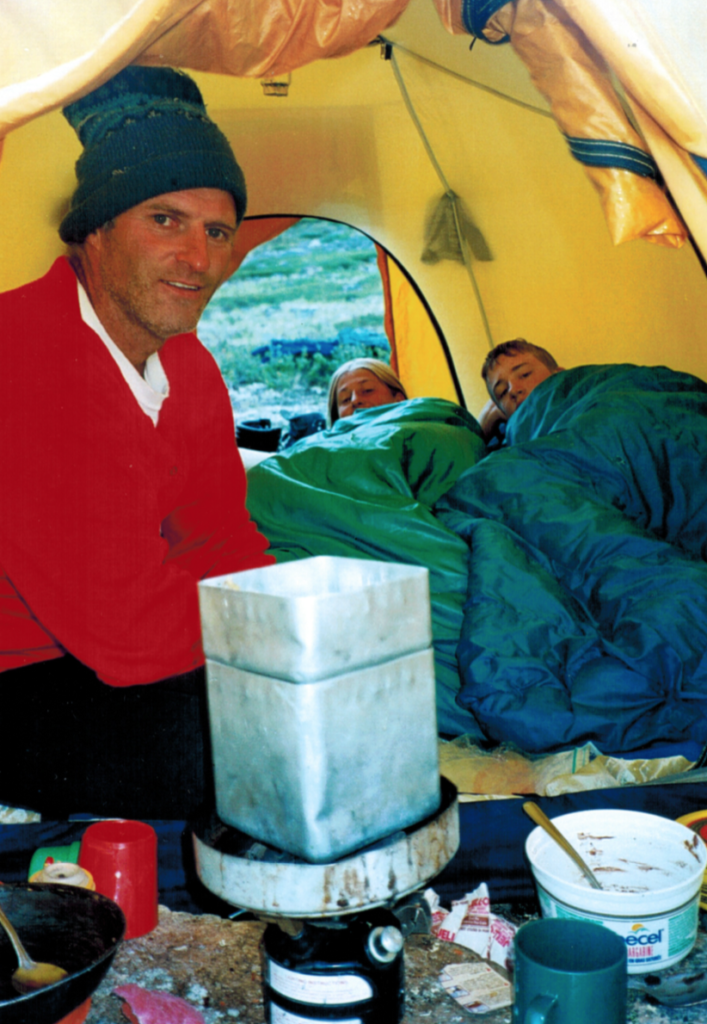

Back at camp, snuggled in the tent with our fellow compatriots, the soup was hot, our stomachs grateful, and the mood spicy as all four of us discussed, dissected, revisited and basked in the adventures of the day.

“We glassed you guys going up the slope,” Pete said. “Every time Jodi looked, there you were, stopping for a pee. She couldn’t believe it!”

“Dad drinks too much coffee in the morning. He can’t help himself. Besides, you guys are supposed to be looking for rams. I only peed after we spotted the big ram. The excitement got to me,” Graeme grinned.

“That’s so disgusting,” said Jodi.

“We’ll find some big rams tomorrow and see what Jodi does,” said Pete, immediately putting his arms up in a valiant attempt to deflect some vicious womanly punches coming his way. It continued this way for some time before we all gradually nodded off, contented with feelings that come in the wilderness when morning promises coffee, bacon, oatmeal, hoping and scheming.

The short grasses just outside the tent were glazed with white frost early the next morning as I leaned out the front vestibule, turned on the stove gas, and waited for the orange flame to turn to blue, listening to the hissing sound that promised piping hot water for coffee or hot chocolate.

Pete and I did the fatherly thing, made the hot drinks and passed them back to Jodi and Graeme who were enjoying a few more minutes in their cozy sleeping bags. Breathing in the crisp mountain air infused with the sound and smell of the last 8 slices of bacon sizzling into greasy goodness, while sipping cowboy coffee, already made it a great day in sheep country. After the bacon and oatmeal, fueled by anticipation and a second cup of strong, black coffee, we had a decision to make.

“Seeing as it’s our last day, why don’t we stick together and investigate that little basin over the high ridge where we found those five rams last year?” suggested Pete.

“We could be up there by one o’clock but if there’s nothing there, then what?” I asked.

“Pete and Jodi could continue around the mountain and you and I could go back and look for the big one,” Graeme suggested.

“And what if we find another big one,” asked Jodi. “Who gets first crack at him?”

“You can shoot while Vern and Graeme take a pee,” Pete laughed.

Part IV: The Decision

It was now three o’clock of that last afternoon. To focus on the eight rams at hand seemed to be the sensible thing to do, but as in the game of love, questions arose. Do you pursue something you feel may be within your grasp or do you pine for that which seems more elusive, rarer and harder to find? Do you accept what is good or do you pursue only the best with a great chance of ending up with nothing at all? Alas. I’ve often wondered how the great questions of life itself become evident during a humble sheep hunt. Is this the real reason we do these things with our children?

“It’s up to you, Graeme,” I said. “What do you think? Do we take our chances here or see if we can find the big guy?”

“Let me take one more look.” Graeme set up the spotting scope on a flat rock, adjusted its sightline by inserting slivers of shale under and around it, put it on thirty power and took his time scanning over the four biggest rams. “Let’s go, Dad,” was all he said as he slipped the scope back into its protective sock.

We left Pete and Jodi there to wait out the eight rams in the valley. Climbing down from the high ridge, we side-hilled back around the mountain across a wide, flat shoulder and stopped just under the crest of a lower ridge to avoid being sky-lined. We began to glass the valley below and the ragged edge of the mountain above and to our right where we had last seen him yesterday. A ram was silhouetted against the skyline on the dark cliffs above the pass at the head of the valley! With trembling hands, Graeme set up the spotting scope, first finding the sheep and then changing the focus from blurry outline to a sharp image of thick, golden horns curling down and around before tapering up and out to perfect tips. “It’s him!” he blurted out.

“What do you think he’s going to do? They usually start feeding around this time. Should we wait?” I wondered out loud.

“There’s no grass up where he is. He’s going to have to move up or come down to those grassy patches by the pass. If he does that, we can sneak right up behind those boulders,” Graeme schemed.

I picked up some dried leaves, crushed them and tossed them in the air. “The wind’s good, too. It’s coming right towards us. Let’s wait and watch for a while.”

We thought our prayers had been answered when the ram finally got up and made his way steadily down towards the pass, but instead of feeding on the other side he turned toward us, came down the steep incline, trotted to the first patch of grass and started to work his way along the valley towards us. We froze. Here we were, caught out in the open again with no cover. The ram must have sensed something was amiss as he alternated between feeding and looking up at us, now almost directly above him.

“What do we do now?” asked Graeme. “We’re hooped.”

“As long as we don’t move a muscle while he’s looking at us, we’re still OK,” I said.

“If we could get our whites on we could crawl out of sight,” Graeme suggested.

“Great idea, but how do we get them on with him right there?” I asked.

This became our plan. I stayed perfectly still, elbows resting on my knees holding the binoculars steady on the ram. Every time he put his head down to feed, I said, “Go,” and Graeme would work at getting his white coveralls out of the pack and on. Whenever the ram looked up, I hissed, “Stop!” and Graeme froze. It felt a little like the children’s game, “Simon Says,” with the ram in complete control.

After Graeme crawled safely out of the ram’s sight, I followed the same procedure with Graeme keeping a careful watch through a large crack between the boulders he was hiding behind. At one point I wondered whether Graeme was playing a joke on me or enjoying the control, since he whispered, “Stop,” just at a point when I was in an awkward position, with my white rump protruding in a rather ungainly fashion towards the open sky while trying to slither around a large rock. I had to hold this position for a considerable period of time and started questioning how long a ram could look at a large, unattractive rear end before deciding it was not posing any immediate danger.

It was right after we were out of his sight that the ram decided to bed down directly below us. Trying to stalk from the left would mean we were in plain sight. Going around from the right, our scent would betray us. What to do? We could not wait and observe because the day was winding down, nor could we pursue a traditional stalk without being seen or smelled. It was time to romance the ram.

Part V: Romancing the Ram

Twenty yards to our left was a small tributary, flowing straight down towards the ram. The boulders erratically spaced on each side of it afforded little cover, but we had no choice. We would slither straight toward the ram, hoping that our whites would convince him that these were two eligible ewes, slowly and nonchalantly making their way down the slope towards him.

As hands, knees and elbows bore down on sharp points of pebbles, rounded rocks and smooth sand, I led the way with Graeme right behind. It was ten yards at a time, a pause to catch our breath, and then another ten, in and out of sight, giving the ram fleeting glimpses of a shapely front leg or a swiveling hip gyrating seductively around a large boulder. I took care to keep an ugly bearded complexion low to the ground and gave a quick peek through the binoculars, then continued. The white plastic painter’s coveralls were soon sporting holes and rips. They were also incredibly hot.

Far down the slope was a large, flat rock, the last bit of cover. This became our chosen destination. I told Graeme, “If we can get to that rock, we might think about a shot.”

We got there – but could we get closer? I held the binoculars forward while slowly edging up to take a look over the flat boulder. At this, the ram got up, looked straight into my binoculars, scraped the ground with his right front foot a few times, circled his bed twice, and bedded down again. I took a deep breath and in slow motion slid back down into the small crevice next to Graeme.

“Your turn,” I said. “Take a look but move really, really slowly. He may be onto us.” Graeme carefully inched forward and up to take a look. This gave me a moment to consider the sage advice an old-timer gave me when I first started sheep hunting thirty years ago.

“Sheep hunting isn’t that hard, Vern. All you have to do is be patient – wait until the ram is in a vulnerable place and then use the cover to get as close as you can. That’s what a good hunter does. Anybody can take long shots but remember – bad stuff can happen when you try that.”

Memories also flashed through my mind of the three biggest rams I had been fortunate enough to take, all over forty inches, taken at 30, 70, and 125 yards. Like the old timer said, a good hunter should be able to wait, use the cover, and close the distance, but here we were, out of time, out of cover, and out of options. Should we take the chance? Which was wiser: to be cautious and listen to doubt? Or decide that confidence would prevail?

Certainly the distance was beyond our preferred comfort zone. Could the old, weather-beaten .308 be counted on? Was my estimate accurate? What difference would the downhill angle make? Should we take the breeze into consideration even though it seemed slight? With the sheep lying down, was there enough vital area exposed?

On the plus side, Graeme had a solid rest, the sheep was broadside to us and not moving, and the rifle sighted in with 150-grain premium, boat-tail ballistic tips to shoot three inches high at a hundred yards. I had memorized the bullet trajectory well, and this was the only rifle I had ever hunted with since I was seventeen. Even more importantly, in our practice sessions and on two previous hunts, Graeme had proven himself to be a very focused and accurate shot.

“Do you think he’ll stay there if we try and get closer?” I whispered, not wanting to make the final decision on my own. It felt strange to whisper quietly with the heart pounding and every nerve on end.

“No, I think he’s going to spook and I’m not going to shoot with him on the run. I don’t want to wound him. I’d rather try a shot from here where I can take my time and have something to rest the gun on,” Graeme hissed.

“I think you can get him from here. Let’s get set up.”

I slipped off my fleece jacket from underneath the white coveralls, rolled it up, and placed it forward onto the rock so Graeme could use it for a partial rest. Graeme slowly slipped the gun up on top of the fleece, slid it forward over the edge of the large, flat boulder, and put his hand under the front part of the stock resting on the fleece so the barrel wouldn’t jump at the shot. He slowly turned his face back towards me and whispered, “Where should I put the ‘X’?”

“There’s a bit of a breeze from the right so aim about four inches behind the shoulder and hold just above him so you can barely see daylight under the crosshairs. Whatever you do though, get a rock-solid steady hold and squeeze very slowly, so you don’t even know when it’s going to go off.”

“I can do that,” he said and flashed a determined smile.

“I’ll keep an eye on the ram with the glass. Take your time,” I whispered and gave him a quick squeeze on the shoulder. “You can do this.”

I focused on the ram as Graeme shifted his body endlessly — trying for that rock-solid, steady hold. The rifle finally roared, the ram lurched to his feet, swayed, and toppled over, all four feet in the air, and then lay still. Graeme and I looked at each other almost in disbelief. “You got him!” I yelled. Graeme grabbed me and lifted me right off my feet. We hugged, danced and made incomprehensible manly utterances.

“I squeezed like no man ever squeezed before!” Graeme blurted out.

We finally forced ourselves to calm down, stripped off our whites, scrambled up to collect our packs, and made our way back to the flat rock and down to the ram. We took turns holding and feeling the knobby horns, admired the tight curl and perfect tips, took pictures, and dressed him out. The bullet had gone right through the heart.

Since the evening was upon us, and the ram was only a half-hour walk from camp, we propped him open so that the precious sheep meat could cool quickly and headed for the tent.

It was 11:30 and almost dark when Pete and Jodi stumbled into camp. Graeme and I had decided on a conspiracy of silence, so we listened attentively as they told their tale of woe. Pete had positioned Jodi on the ridge with his rifle and made a large circle around and below the rams in a valiant attempt to nudge them onto the escape trail. In their own unpredictable, elusive way, the eight rams decided to go a different route and ended up on a steep, rocky chute instead with the rifle-less Pete gazing up at them from 80 yards below, softly saying uncomplimentary things in German so they wouldn’t understand and hold it against him. Jodi never did get a chance at them.

After the breathless recounting of their adventure, Graeme quietly said, “We got the big one,” and the whooping and hollering started. The headlamps illuminated a late supper of Kraft mush, instant pudding, and hot chocolate, which accompanied much joy, considerable exuberance, and a detailed recounting of every strategy, feeling, and minute detail of the stalk.

We had eaten ourselves out of the normal breakfast food, so the next morning it was a quick menu change to Itchiban noodles and pepperoni sticks with only one cup of cowboy coffee each to mitigate the strange taste. Why linger when there is a gorgeous ram to go back to?

When we got to the ram, Graeme took another opportunity to describe the stalk, point out the flat rock far up the slope, relive the moments before and after the shot, and again hold and admire those horns together with Jodi, Pete, and myself.

After we caped the ram and boned out every bit of meat, it was short walk back to camp for a hot lunch cooked up by Jodi and Graeme, and then time to break camp.

We zig-zagged our way up the shifty rock slide, over the snow at the pass, across a wide plateau, and bedded down in the late evening, setting up the tent next to a pool of water that oozed out from under a moss-covered rock and trickled on through the meadow of alpine flowers.

Part VI: The Afterglow

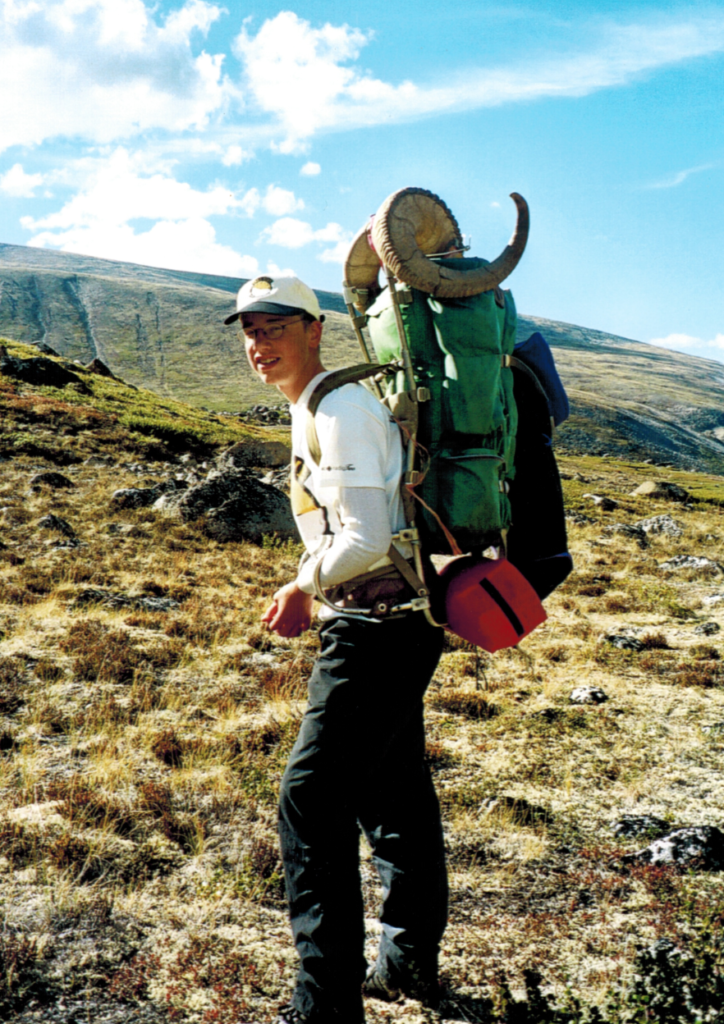

On the last day hiking out, I stayed behind Graeme, content to follow those golden horns and watch them sway from side to side as he walked, feeling no regrets, no thoughts of what might have been, only a sense of blessing and deep gratitude.

It was with a pleasant weariness that we slid the packs off our sweaty backs next to the truck after two long days of trekking. It was over – until next year. We had waited and observed, run and pursued, and in the last hours, made things happen. Graeme had also made a tough decision to choose the best, unreservedly, and was rewarded.

Years go by and young men leave to make their own adventures, but whenever Graeme comes home, we take some time to look at those horns, relive the moments, feel the emotions, and remember the terrible beauty of that place. He doesn’t have to say much — we’re men you know — but whenever we gaze at those horns together, he slips his arm around my shoulders and squeezes hard.

That is more than enough for me.