Are we closer to an answer?

In our first installment of “How Far,” my friend Jerry and I were preparing for a mountain hunt that might entail shooting at substantial distances when he asked me, “Just how far is too far?” His concern for ethical hunting was admirable, and a bit of nervousness over one’s shooting abilities is generally much preferred to unfounded overconfidence. How should I answer his question?

We explored some of the controversies and ethics involved in long-range hunting. Now we’ll explore some of the tools involved. Once again, I turned to the experts at Nightforce, since their riflescopes are renowned for their long-range capabilities.

“We make the tools that make extreme long-range precision possible,” said Sean Murphy, Nightforce’s marketing communications manager. “That doesn’t mean you are instantly an expert with those tools. Some scope manufacturers imply in their advertising that all you need to do is buy one of their products, slap it on your rifle, and it will make you a 1000-yard shooter. That, in our opinion, is unethical. Buying expensive power tools does not make you a master carpenter. It takes a whole lot of practice, trial and error, hard work and learning from your mistakes. In hunting, you’re pursuing a living creature. You don’t want to make a mistake under those circumstances.”

Indeed, Nightforce goes out of its way to preach the gospel of constant practice at the range and shooting hundreds, if not thousands, of rounds. They would prefer you didn’t buy a Nightforce riflescope if you’re not willing to make the commitment to use it ethically. Wounded animals are bad PR for Nightforce and for the hunting and shooting communities in general.

“Modern reticles have played a huge role in extending the ranges of precision shooting,” Murphy continued. “Reticles like our MOAR [MOA-based] and MIL-R [mil-radian-based] take all of the guesswork out of holdovers if you know the distance to your target. A high-quality riflescope, with absolutely repeatable, precise elevation adjustments, also allows the shooter to ‘dial in’ elevation compensation at well over 1000 yards. While these reticles, as well as elevation adjustments, are extremely simple to use once you understand the concept of minutes of angle or mil-radians, it is not something you want to figure out for the first time when you have a game animal in your crosshairs. You want to have done your homework on the range, at every conceivable distance, so it becomes second nature when you’re hunting.

“Unfortunately, some companies make the same claims about their reticles as they do with their riflescopes. Yes, there are drop compensation reticle designs that do work reasonably well. But, your rifle, bullet and load throws several variables into the mix. You must verify—through actual shooting—anything a manufacturer promises you.”

You would be hard pressed to find any professional shooter using anything other than a very simple reticle. Gimmicks have no place in that environment. “Competition shooters fire thousands and thousands of rounds per year,” Murphy said. “They know their rifle and loads as if they were married to it. Many competition shooters’ wives think they are.”

So, let’s say you’d like to start pushing the envelope of your own shooting prowess. You have a flat-shooting rifle, and you’re willing to put in the time and effort to shoot effectively at 600, 800, even 1000 yards or more. At that point, it all comes down to optics. Namely, your riflescope.

We’ll ignore all the manufacturers’ claims, and focus on some of the things that in fact make a riflescope capable of long-range accuracy; things you should look at closely when shopping for one.

First and foremost is the glass. High-quality lenses are expensive. You will encounter terms like “multi-coated,” “HD glass,” “high contrast,” “light gathering” and more. Without knowing what they actually refer to, they are nothing more than marketing buzzwords.

“HD,” or high definition, means something in your television, but not in your riflescope. “ED” glass, however, does. “ED” stands for “extra-low dispersion.” With a standard lens, different light wavelengths do not converge at the same point as they pass through. ED glass focuses these wavelengths to a much more precise point. By reducing color dispersion, the image produced has brighter color, higher resolution and better image contrast. The farther away your target, the more critical these attributes become. All contribute to the clarity and brilliance of the image you see, which in turn affects your ability to properly identify your target and place an accurate shot. As has often been said, “You can’t hit it if you can’t see it.” Only the finest riflescopes are built with ED glass, such as the Nightforce ATACR series, and they are purpose-built for extended-range shooting.

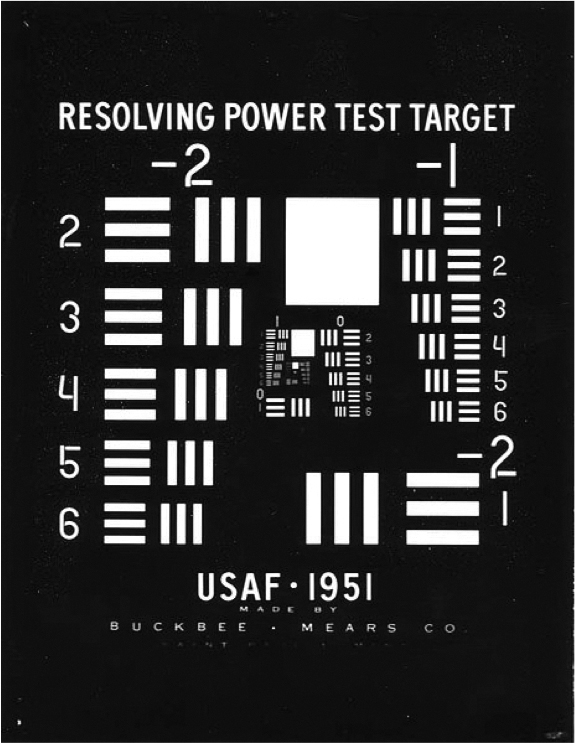

Resolution is the ability of the lenses to resolve the image and distinguish fine detail at extreme ranges. Few manufacturers talk about this, because they really don’t want to answer uncomfortable questions. Resolving power can be accurately measured with charts designed for that purpose. An interesting test for comparing different riflescopes’ resolution can be done by tacking up a newspaper at 100 yards and seeing which lines you can read with each.

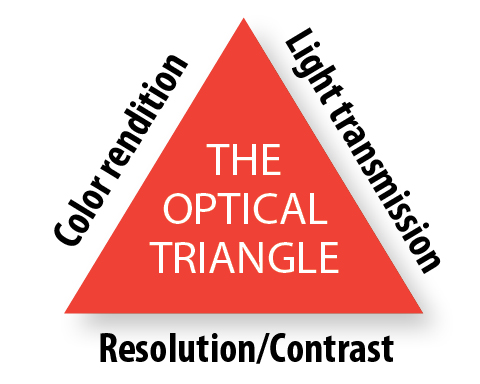

Contrast, or color contrast, is a scope’s ability to distinguish different shades of the same color in a static image…for example, a brown animal standing among brown trees on a brown hillside. Contrast levels are manipulated by a riflescope’s optical design in conjunction with lens coatings.

Speaking of lens coatings, almost every scope maker touts their “multi-coated” lenses. What does that really mean? By itself, not much. There are inferior coatings, average coatings, and exceptional coatings. The “exceptional” level incorporates highly sophisticated chemical compositions. They can actually be tailored to transmit certain wavelengths of light that are more visible to the human eye at dawn and dusk. Good lens coatings, applied properly in a laboratory environment, also reduce glare and influence the accuracy—and contrast—of the colors you see. In the best riflescopes, lens coatings are actually tailored to complement the specific chemical composition of the lenses to which they are applied.

Light transmission is another area of vital importance in a riflescope’s performance, especially at extended distances. Light transmission is the measure of how much light enters the objective (front) of your riflescope and ultimately reaches your eye. It is physically impossible for a scope to transmit 100% of available light, since each lens, as well as other internal elements, absorbs a small percentage of the light passing through it. Even the finest lenses (and there are several in a variable-power scope) each absorb between 1% and 1.5% of the light that enters. Cheap glass sucks up light like a sponge. The best riflescopes on the planet will transmit a little over 90% of the light that enters. This figure plummets with lesser-quality optics. Unfortunately, some scope manufacturers greatly exaggerate their products’ light transmission capability, for example, by publishing data obtained only by measuring one lens—not all of them within the scope. Don’t let anyone tell you there is such a thing as a “light-gathering” riflescope. A scope can only transmit—not “gather”—available light.

Color rendition, light transmission, and resolution/contrast are the Holy Trinity of optical design—referred to as “The Optical Triangle.” There are simply no shortcuts in achieving the maximum possible performance on each side of this triangle. These sides are often at odds with each other, requiring a delicate balancing act. The materials, technology, manufacturing processes and engineering involved are demanding and expensive. Why does one scope sell for $300 and another for $3000? It isn’t markup or status you’re buying at the upper end of that range. You’re paying for the maximum possible performance, durability, resistance to recoil and repeatability—all of which are essential when determining “how far is too far.”

The longer the shot, the longer the odds—and you want the odds on your side as much as possible.

* * *

Next: In Part Three, the author tries—and fails—at 1000-yard shooting. We’ll look at more of the factors that influence long-range precision, and we’ll revisit the ethics of long-range hunting. And yes, Jerry will get his answer to “how far is too far.”

About the Author:

Tom Bulloch has worked in the optics industry for over 21 years. He has hunted on six continents, doing, as he puts it, “more hunting for less money than any man alive.”

His credentials as a mountain hunter include two ibex, bighorn and Dall sheep, a mountain goat, tahr, chamois, mouflon, and many timberline elk and mule deer. He lives at nearly 9000 feet in the Colorado Rockies, where, he says, “even looking for my car keys is a mountain hunt.”