The hide boom only lasted a dozen years before the buffalo ran out. The first big hunting push was in the vicinity of Dodge City. In 1871, the first big year, the hide hunters killed so many animals so close to town that residents complained about the stench of rotting carcasses. That winter, a half-million buffalo hides were shipped out of Dodge. The hunters spread out from there, organizing their hunts along the eastward-flowing rivers of the Great Plains. They hunted out the Republican River, near the Nebraska-Kansas line. Along the south fork of the Platte River, hundreds of buffalo hunters lined fifty miles of riverbank and used fires to keep the buffalo from getting to the water at night. In four daytime periods, they gunned down fifty thousand of the thirst-crazed animals. Within a year or two the hunters had cleaned out the regions immediately to the north of the Arkansas River, and then they hunted out the watersheds of the Cimarron, Canadian, and Red rivers. The hide hunters pushed south into the Texas Panhandle and southwest Oklahoma. Soon, hunters who outfitted in Dodge were straying so far from home that their hides were shipping out of Fort Worth, Texas. By 1878, there weren’t enough buffalo on the southern plains to warrant the chase.

The Texas hunt was followed by a brief lull in the action while a new railroad, the Northern Pacific, cut into the northern range. Once the railroad made it to Miles City, Montana, in 1881, word spread that the core of the last great herd had been tapped. Hide dealers calculated that 500,000 buffalo ranged within 150 miles of town. Soon there were five thousand hide hunters killing the ani- mals. A herd that was estimated at seventy-five thousand head crossed the Yellowstone River three miles outside of Miles City, moving north as a great mass. Hunters stayed with the buffalo like sheepdogs, pushing them along. Accounts vary, but anywhere from zero to five thousand buffalo were all that was left by the time the herd reached Canada. By 1883, the one remaining large herd had moved into the Black Hills. It started out as ten thou- sand buffalo and was quickly reduced to one thousand by white hide hunters. Then the Sioux warrior Sitting Bull and a thousand of his men fell on the herd and killed the rest. A man who took part in the slaughter said that “there was not a hoof left.”

When the hide hunters were done, the skinned-out carcasses that they left behind rotted down, and green grasses sprang up in the places where the juices oozed. Then the green grass turned brown in the fall, and the carcasses were picked down to the bone by scavengers. The bones turned white in the sun. At that moment it might have seemed as though there was nothing more that we could get out of the buffalo, but there was. Makers of fine bone china began to purchase the best of the bones, those that weren’t too dry or weathered. Burned to ash and added to ceramics formulas, the bones gave American- and English-produced porcelains a translucency and whiteness that could compete with imported Oriental china. Other big consumers of quality buffalo bones were the sugar, wine, and vinegar industries; they had been using wood ash to neutralize acids and clarify liquids, but in the early nineteenth century they found that bone ash did a better job of making sugar more shiny and wine less cloudy. Industries also used buffalo bone ash in fine-grained polishing agents and baking powders. Metallurgists found that bone ash was useful in the process of refining minerals.

By far, the biggest consumer of buffalo bones was the fertilizer industry. It didn’t care so much about quality; cracked, dried-out, dirty bones were just fine. Workers would grind them into a coarse powder known as bonemeal, which can be tilled into nutrient-poor or acidic soils. Firms that produced buffalo bone- meal fertilizer managed to sell a lot of the product to homestead- ers on the Great Plains who were trying to produce corn and wheat on lands recently abandoned by buffalo.

The homesteaders who bought buffalo bonemeal were often the same people who’d been picking the buffalo bones up. Upon their arrival in the wake of the hide hunters, homesteaders burned whatever buffalo chips were lying about, and then they were forced to burn buffalo bones as heating and cooking fuel. The smoke from these fires smelled just like burning hair. Some men found the buffalo bones to be an encumbrance to tilling and working the soil. A homesteader arrived in Nebraska and cursed the bones.

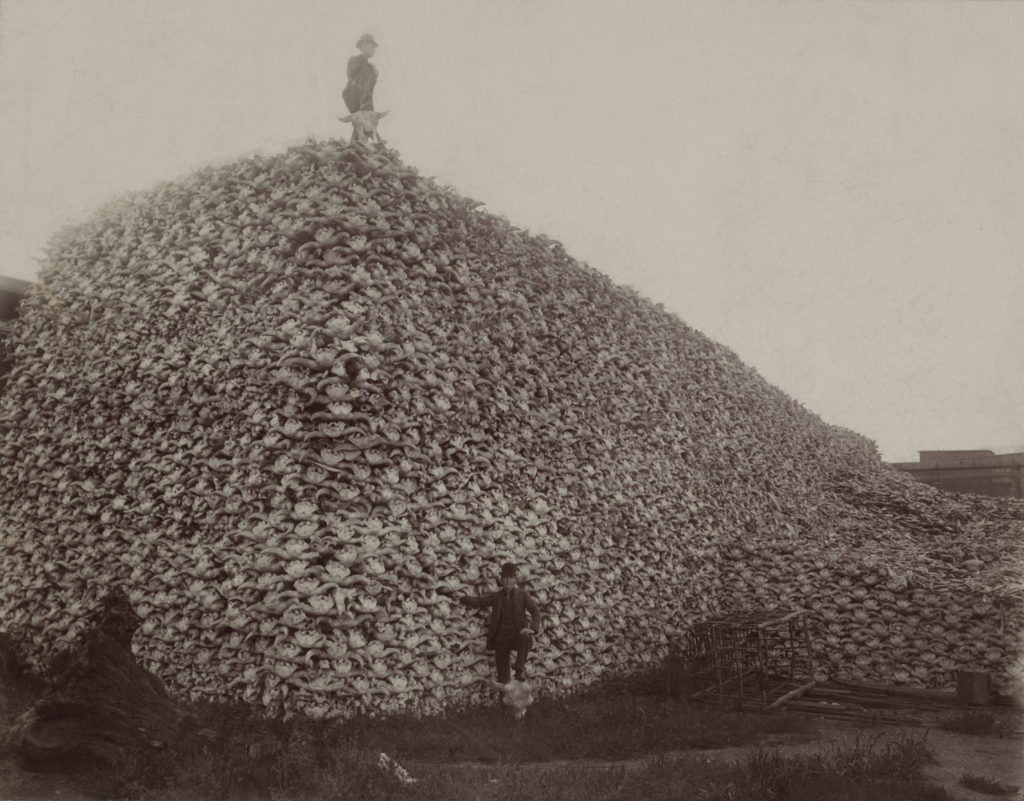

Remains of a hide hunter slaughter somewhere in Canada

“Buffalo bones was laying around on the ground as thick as cones under a big fir tree,” he said, “and we had to pick them up, and pile them up, and work around them until we was blamed sick of ever hearing the name buffalo.” Settlers stacked the bones in great heaps and torched the stacks. When the bone market developed, or when railroad spurs reached their “neighborhood,” the settlers took to selling bones. For many, buffalo bones were the first cash crop to rise up out of their newly ac- quired dirt. An advertisement on the front page of the July 23, 1885, edition of North Dakota’s Grafton News and Times read: “Notice to Farmers: I will pay cash for buffalo bones. Bring them in by the ton or hundred. I will give fifty pounds of the best twine for one ton of bones, for this month only, or a $40 sewing machine for forty tons. I want 5000 tons this month.”

A train car could haul the bones from approximately 850 buffalo. Stacked alongside the railroad tracks, bones fetched $8 a ton. It took about a hundred buffalo skeletons to make a ton of bones, so each animal’s skeleton was worth eight cents. If the bones were wet, it might take only about seventy-five skeletons, so a burst of rain on a pile of dried bones was considered a good thing by bone pickers. In all, the money was good enough to inspire many bone pickers to go full-time instead of just cleaning up their own land. A man named George Beck and his brother hunted bones outside of Dodge City. The Beck brothers operated with two wagons and two teams of oxen. They camped under the stars and cooked bread, bacon, and sweet potatoes over buffalo chip fires. When their wagons were filled, they hauled them to the wagon trails connecting Dodge City to peripheral military forts out on the wild prairie. They would dump their load and paint their mark on a prominently displayed skull. Government freighters who sup- plied goods to the forts would fill their empty wagons with the Becks’ bones on the way back to Dodge City and then drop the bones at the railroad tracks.

On the northern Great Plains, a group of Indians gathered 2,550 tons of buffalo bones in anticipation of a railroad coming through. In Kansas, bone pickers accumulated a pile of bones along the Santa Fe Railroad that was ten feet high, twenty feet wide, and a quarter mile long. The Santa Fe was greeted outside Granada, Colorado, with a mound of bones that was ten feet by twenty feet and a half mile long. Railroads would build spurs from the main line just for the sake of collecting stacks of buffalo bones. It was good business for them. The Empire Carbon Works, in St. Louis, processed 1.25 million tons of buffalo bones during the buffalo bone era. It paid on average $22.50 a ton. That’s over $28 million paid out for buffalo bones, which came from perhaps 125 million skeletons—or more than four times the number of buffalo that ever existed at any one time.

Before the buffalo bones were all picked up, people traveling through buffalo country reported bones so thick on the ground that they looked like fallen snow. If you could have watched the bone pickers’ progress in time-lapse photography taken from outer space, it would have looked like the snow was melting ahead of a great westward-moving heat wave. The wave traveled fast, pushing up river valleys and railroads first and then spread- ing outward until there was hardly a bone left anywhere. By 1890 it was hard to find a buffalo bone south of the Union Pacific Railroad. As the skeletons petered out, the fertilizer and carbon industries announced a “bone crisis.” Prices shot up. Indians be- gan digging bones with shovels and picks beneath buffalo jumps that dated to the birth of Christ. They once believed that these bones were capable of rising back up into brand-new buffalo, but times had changed.

The Detroit Public Library houses a famous photo from around the time of the bone crisis. It shows a mountain of stacked buffalo skulls that’s thirty feet high at the crest and hundreds of feet long. The photo was taken in a rail yard at the Michigan Carbon Works in Detroit, a place that locals called “Boneville.” I’ve driven past there several times—crossing the Rouge River on the I-75 bridge, you can look down and see the exact place. It would require an involved feat of extrapolation to calculate just how many thousands of skulls were in that heap. The most inter- esting thing about the photo is the man standing at the top. Wearing a suit and top hat, a large buffalo skull propped against his leg, he resembles an exclamation point standing at the top of a very long sentence about death and destruction.

Since the end of the buffalo bone days, the Michigan Carbon Works has downsized dramatically. The agricultural industry turned away from bones and began using pulverized phosphate rock as a source for phosphorous fertilizer. Many old markets for bone carbon are now satisfied by carbon black, a by-product of fossil fuel combustion that is otherwise known as soot. Today, what’s left of the Michigan Carbon Works is a small company called Ebonex, located on South Wabash Street in Melvindale, Michigan. They burn cattle bones to create ash that is used as dye in colored plastics, coated paper, wood stains, and paints. The Food and Drug Administration has given bone ash GRAS status, or generally regarded as safe. It’s used to treat water on fish farms, and it’s used in water filters for household aquariums. They also sell a lot of bone ash to movie production companies that want to replicate oil spills. Mixed with vegetable oil, bone ash makes a biodegradable dead ringer for Texas tea. If you’ve seen The Beverly Hillbillies, Die Hard 3, Men in Black, Fear and Loathing in Las Vegas, or Jarhead, you’ve seen the contemporary products of a company that once produced about 650 tons of buffalo bone ash every year.

In 2005, Steven Rinella won a lottery permit to hunt for a wild buffalo, or American bison, in the Alaskan wilderness. Despite the odds—there’s only a 2 percent chance of drawing the permit, and fewer than 20 percent of those hunters are successful—Rinella managed to kill a buffalo on a snow-covered mountainside and then raft the meat back to civilization while being trailed by grizzly bears and suffering from hypothermia.

American Buffalo is a narrative tale of Rinella’s hunt. But beyond that, it is the story of the many ways in which the buffalo has shaped our national identity. Rinella takes us across the continent in search of the buffalo’s past, present, and future: to the Bering Land Bridge, where scientists search for buffalo bones amid artifacts of the New World’s earliest human inhabitants; to buffalo jumps where Native Americans once ran buffalo over cliffs by the thousands; to the Detroit Carbon works, a “bone charcoal” plant that made fortunes in the late 1800s by turning millions of tons of buffalo bones into bone meal, black dye, and fine china; and even to an abattoir turned fashion mecca in Manhattan’s Meatpacking District, where a depressed buffalo named Black Diamond met his fate after serving as the model for the American nickel.

Available online for purchase: