“Make sure you pick your weather; nothing’s worse than getting all the way in there and being stuck in the tent for a week.”

Those words kept echoing in my mind as the lightning lit the evening sky and the thunder boomed among the peaks. The roar was deafening as the air sizzled from the constant flashes. The rain fell in sheets and water was running down the trail we were riding, leaving the granite as slick as a river stone. The horses were tired, I was tired, my Dad was tired, and at that moment we weren’t real sure how much further we had to go until we reached the campsite we had picked out the weekend before. The only variable that we knew positively was that we had to cross the creek before we could stop. By tomorrow, we knew the creek was going to rise — but exactly how much, we had no idea. We only knew that we had to make it across while we still could. As another clap of thunder shook us to our core, I couldn’t help but wonder if we were going to make it through this…

After only seven years of applying, I had drawn an archery mountain goat tag for my home state of Colorado. The season opens in early September and runs all the way through October 31st. The area is well known to be one of the roughest — not only because of the awe-inspiring, jagged peaks, but also for the pure elevation. In the heart of the 499,771-acre wilderness these goats call home, there are multiple 14,000-foot peaks, and the valley bottoms are roughly 9,500’. More than one aspiring goat hunter has drawn this tag only to turn it back in after visiting the area. The sheer magnitude of the country cannot be described in words that adequately explain the daunting task of hunting goats in this area.

With that said, the irony is that this hunt boasts a high success rate. While a physically demanding hunt, there is a healthy population of goats that roam the area, and they are highly inquisitive of the many mountaineers they see throughout the summer. This is an either-sex tag and there is no shortage of goats to choose. Looking back through the records, there are many nannies taken, which Colorado Parks and Wildlife is more than happy to see. They are hoping to keep numbers stable and are concerned about having goats spread to adjacent ranges.

But simply any goat wasn’t what I was after. My dream goat was an old, warrior billy with his long, white coat primed for the brutal winter this area receives — and with a lot of luck, ten inches of length in his horns.

Most goats harvested in the area are taken in a large basin that seems to be the focal point for most hunters, simply because of the access. It is well known for the nannies and younger billies that inhabit the area, and a person can catch a ride on the train to within six miles of the basin. The areas I chose to hunt would be harder to reach, but the potential for a nice billy was far greater.

In the months leading up to the hunt, I scouted basins that weren’t known for having a lot of goats because I was hoping to find a big, rogue billy that was looking for solitude. On a solo trip in mid-August, I ran into a herd of goats — that was mostly nannies with kids and young billies — and managed to get within 30 yards of the group. My confidence was running high after the encounter, but I still had not found the billy I was looking for.

A few weeks after seeing the big herd of goats, I was again making the three-hour drive for a scouting trip. I had contacted a well-known taxidermist in the area who is also a noted sheep and goat guide for the state of Colorado. He was hunting the unit before it had gained any traction among other hunters in the state and at one point he drew the tag five years in a row. He was more than accommodating, answering all my questions, and his advice proved to be spot-on. His last statement would be the advice that kept cycling over and over in my mind: “I’ve seen it snow up there in the middle of August. Make sure you pick your weather; nothing worse than getting all the way in there and being stuck in the tent for a week.”

I made a plan to sit out the first couple weeks of the season and hunt the first week of October. I thought that by that time the goats would be wearing a prime winter coat, and it would also allow me a few more weeks to hunt the remainder of the season if I didn’t take a goat during the planned week. The weekend before I planned to start hunting, my Dad thought it would be a good idea to take a ride up and finalize a place to camp. From the trailhead up to where we wanted to establish a base camp was going to be around an eight-mile ride. As we saddled the horses, a person could not have asked for a more beautiful day. The sun was casting rays of golden light across the ridge as a gentle breeze whispered in the pines. We made the ride up the trail in no time and ate lunch in a meadow that seemed perfect for camp. It offered great views of the surrounding slopes as well as fresh water from the nearby creek.

As we turned back to head for the truck, the ominous and often present high-country clouds began building among the peaks. We reached the switchbacks to climb up to top of the ridge, and the skies opened and let us have it. We rode two miles in the rain and more than once argued with a horse who didn’t want to continue and just wanted to be out of the weather. By the time we reached the truck and put the horses away, the storm had passed and the skies were as blue as when the morning began. As the highway miles raced by on the way home, I could feel the excitement building as though I was hunting tomorrow.

The morning we left for the hunt began dark and dreary. The clouds had settled in with promises of rain, and the weather forecast showed scattered showers for the entire week we had set aside for the hunt. I began to have second thoughts about heading up and I thought maybe we should wait another week before striking out. As I drug my feet trying to decide what to do, I made a critical error. I talked myself out of using common sense, and we hit the road around nine for the drive to the trailhead instead of leaving before daylight like I knew we needed to allow us enough time. We arrived at the trailhead close to noon and went as quickly as possible to saddle two horses and pack the other two horses with camp supplies and equipment for the week.

I have a little saying for times like this: “The brother of hurry-up, is screw-up”. As we scurried around trying to throw everything on the pack horses as fast as we possibly could, nothing would fit like we had planned. We ended up having to unload & start completely over with one pack horse as the precious minutes ticked away and the thunderheads began to form in the direction we would be heading. Finally, at 3:00, we started up the trail only to have my bow case come loose and spook a horse. As he slipped away from my grasp and tore down the trail unchecked, I had no choice but to follow as best I could. Luckily, he didn’t go very far and we were able to re-secure my bow case and continue our adventure. As the skies grew darker and the winds began to gain speed, we reached the set of switchbacks that would take us lower to the creek.

At this particular point in the trail, there is a rock ledge on one side and a 70-foot drop on the other, and as luck would have it; we ran into an outfitter leading his pack string out to the trailhead. After some jockeying around in some precarious spots, we found just enough room to let him squeeze by with his string of eight mules. The clouds seemed to grow larger with each passing minute, and in the distance, we could hear the low rumble echoing amongst the peaks. We kept pressing the horses as much as possible, started to gain the miles towards our planned destination, and except for a few minor hiccups on the bridges with the pack horses that had never crossed a bridge, we made decent time until the light faded.

It was far too late to entertain thoughts of turning back; we were in for the ride no matter what happened. As the low rumble of thunder grew into a roar, the lightshow began to illuminate the now-dark sky. Each time it flashed, I could feel a prickle at the back of my neck. We slipped down another small hill — we had finally reached the crossing. As we eased the horses into the water, I felt a small sigh of relief. The water in the creek was a little above the horse’s knees but running swifter than the previous weekend. With no more than a few minor slips on the moss-covered river stones, we were across but not out of the woods yet; we still had a mile to reach our campsite and we were soaked through our slickers.

As we rounded the next bend in the trail, we came face to face with a big Shiras bull moose. As he stared down the horses, they snorted at the sight and craned their necks to look back the way we had just come. After what seemed like five minutes, he wandered off the trail and vanished into the trees. We gave him a little time to clear out and continued on our way to the campsite. In the dark with only headlamps and flashes of lightning to guide us, we decided that we were as far as we needed to be for the night. The important step of getting across the creek was behind us, so we started looking for anywhere to stop and make camp to get out of the rain. We came to a small clearing and unpacked the gear, hoping the weather would clear so we could establish our camp for the week.

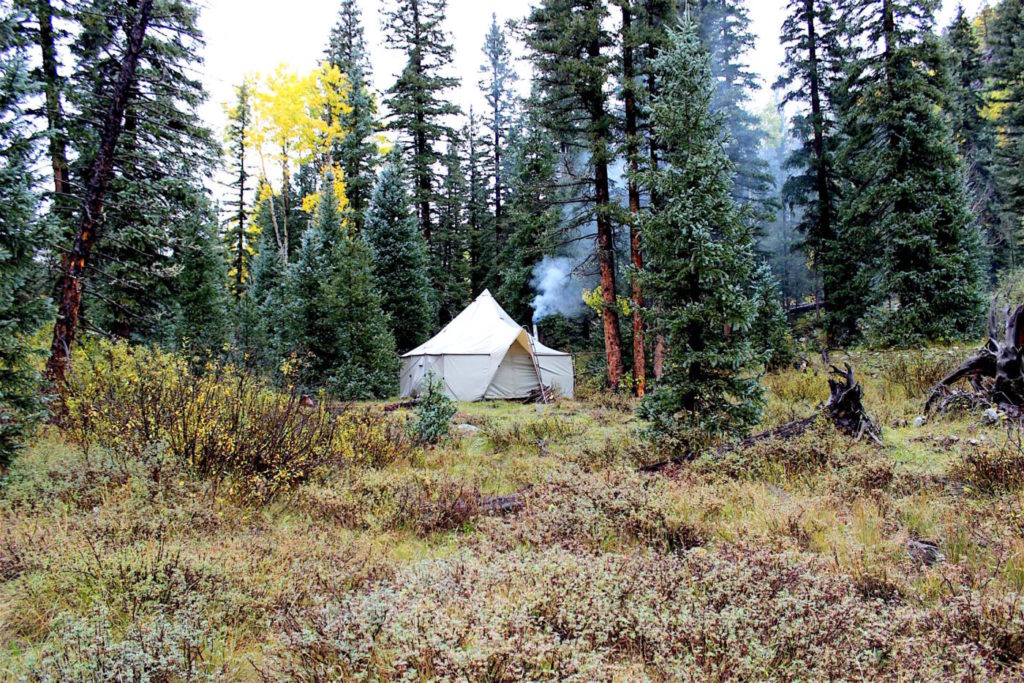

The next day it rained. And rained. For good measure, it rained some more. The second day we were in the tent, the rain began to mix with snow. As we dried out equipment and clothes by the fire, we were glad to have books to pass the time, but even more grateful to have the stove in the tent. By the third morning it had stopped raining, but the clouds were hanging low on the mountains and looked primed to rip open again at any minute.

In the middle of the day as I was huddled up by the stove, I heard the horses snort and opened the tent to see what caused the alarm. Less than 30 yards from the tent flap was a young bull moose trying to figure out what monstrosity had appeared before him. After he had satisfied his curiosity, he hastily trotted up the trail heading for new country.

The fourth morning was clear and cold, but the weather had broken and I was finally able to hunt. I wanted to try a basin where a friend had helped harvest a goat two seasons earlier, so the plan was to ride the horses as far as we could before Dad would bring them back and stay at base camp while I hiked further to spike camp for the night. If I didn’t see anything in the first basin, there was another basin to the north I thought I could drop into that is also known to hold goats.

We started up the trail and when we reached a boulder pile, Dad’s horse decided he had gone far enough. No amount of whipping and spurring was going to persuade him to keep going, and then to my surprise, he went down! The horse flopped on his side among the rocks before Dad could pull his foot out of the stirrup. I was positive that Dad had just broken his leg. The horse stood back up, and Dad struggled to his feet; to my amazement, his leg wasn’t broken. As he hobbled around testing his leg to see how bad it was, the thought of how exactly I was going to get everyone and everything out of the backcountry flashed through my mind. I was preparing to head back for base camp, but Dad announced that his leg was fine and that we might as well keep going.

I knew there wasn’t any point in arguing, and we reached the creek leading into the basin an hour later. After dismounting and making sure everything was set, I hiked into the basin hoping to find a goat but only discovering snow and treacherous, ice-covered slopes. I abandoned any thought of dropping into the adjacent basin, and spent the rest of the day glassing with no luck. Instead of sticking with my original plan of spending the night in a spike camp, I decided to head back to base camp to see how Dad was getting along.

When I reached the tent, it looked like a bomb had exploded. Even with his badly swollen leg and extreme limp, Dad had strung up rope lines through the trees and had saddles, blankets and extra clothes out drying in the sunshine. While he was busy hanging his lines earlier that day, a couple of game wardens happened to ride by camp and stopped to visit. I also ran into them on my hike back out to camp and we had a pleasant chat about the country. They had brought up trail cameras with the intention of gathering data on the reintroduced lynx that were in the area and they also informed me that the week prior, they had spotted goats on a mountain four miles further up the valley. After a freeze-dried meal that evening, I came to the realization that I didn’t have the right equipment to tackle one basin on my list with the icy conditions, so I decided to hike up to the mountain they had mentioned the next morning hoping that the goats would still be around.

The hike up the trail was a brisk, two-hour clip in some of the finest country I have ever seen. Words simply cannot pay tribute to the absolute grandeur of the high country in October. Luckily for me, the trail wound around the mountain, allowing me to glass most of the mountain directly from the trail. I spent a couple of hours picking apart the south side with no luck before moving to survey the north and the east faces.

Around five that evening, after not seeing anything all day except fresh moose tracks, I made the trek back down the trail to camp. To say I was disappointed would be an understatement. I was now down to one day left to hunt. In a last ditch effort to find a goat, I planned to hike a different trail but one that would lead into the popular basin if I followed it long enough.

Just before the drop into the basin, there is an alpine lake in a little bowl off to the west that I wanted to try. As I made my way up the trail, I scrutinized and glassed every peak hoping to find a billy. Late into the afternoon, I reached the destination only to find it void of animals. There would be no goat taken on this trip.

The next two weeks spent at work were pure torture. I couldn’t seem to wrap my mind around anything I was trying to accomplish knowing that I had an un-punched tag in my pocket with goats on the mountain. I tried a mad-dash, three-day weekend trip in between the work weeks but it was unsuccessful. With the last weekend of the season looming, I was feeling the squeeze. I took a few extra days off work to give it everything I had for the remaining days on a solo expedition.

Knowing I didn’t have the time to reach the various basins in the heart of the unit, I opted to try the area where I had run into the herd in a scouting trip. In the prior trip up the trail while learning the country it seemed like the area was overrun with climbers and day-hikers from the train, but with it being this late in the season, there wasn’t a soul for miles except the weasel that seemed to enjoy my company and the herd of elk I spooked. As I reached the dim and hard-to-follow trail into the basin, I changed my mind and decided to camp in the valley where I was and climb into the basin the next morning.

After setting up my tent for the night, I set up the spotting scope, thinking I would enjoy the tranquility more than expecting to see a goat from there; but I was wrong. Roughly a mile and a half up the valley I spotted a patch of white on a cliff. With only an hour of remaining daylight, I knew there was no chance of reaching him, so I resigned myself to only glassing. As I watched him dance through the cliffs and across a waterfall, I tried to visualize a stalk and chart a path to him while wishing he would stay put to give me a crack at first light.

Well before dawn, I rolled out of my sleeping bag and set up the spotter while also making a cup of coffee with my breakfast. My heart sank as the sky began to turn grey that slowly crept into gold; he was gone. I scrambled to throw everything that was not essential for the day out of my pack and into the tent, then I lit off down the trail towards where I had last seen him. After tripping over countless logs because I wouldn’t look down due to being afraid I might miss him, I was directly under the cliff where I had put him to bed.

The only chance of gaining any vantage point was to either head directly up to where I thought he was or to continue on the trail as it gained elevation around a set of peaks until it went over a pass. I decided to stick with the trail, not having any good indication of where he was exactly. The trail slowly wound its way to another set of switchbacks and as I made the first turn out of the pine trees, 600 yards ahead and above me was the most stunning display of majesty I have ever seen. Perched upon a pinnacle of granite overlooking the valley floor was a stunningly white mountain goat.

The long, winter coat fluttered in the breeze as the sun-blazed streaks of gold created a halo that caused to me to pause and revel in the moment. As I gathered my composure, the goat dismounted its throne back onto the bench to come to rest where it could still watch for danger. At that point I wasn’t sure if it was a billy or a nannie, but ironically, my first thought was to get out the camera and get a picture. While I was busy snapping photos, another white spot appeared out of nowhere beside the goat in my viewfinder. It was a nannie with a kid I was watching! I will admit to being a little disappointed, but the image when I came out of the trees was so surreal that I couldn’t be very upset.

I began to wonder if the goat I saw the evening before might have been this nannie and that I hadn’t spotted her kid until now. With not a lot of other options this late in the season, I opted to continue to the pass and check the other side. After another couple of hours hiking, I crested the ridge only to find it devoid of goats. With it already being near mid-day, I elected to head back for camp to push into the basin to the south that had been my original destination before I spotted the goat. The plod back down the trail was certainly easier than the long grind up, and as I walked my mind wandered to all the “what-if’s” I had experienced over those last couple weeks.

My focus snapped back into place when I spotted the nanny again a little higher up this time. While I was watching her, I thought that I could see another white patch roughly a half mile past her, but with the steep upward angle I couldn’t be sure exactly what I was seeing. I was roughly 1,600 feet below the confirmed goat and around 1,800 below the white spot. The best chance to get a better look would be to climb up the other side of the valley through dense pockets of pines that would conceal me while I gained elevation. After a 30-minute scramble, I found a little bench under a pine tree to set up the spotting scope, and it was well worth the effort. On a ledge across the valley from me were not one, but two billies! They had quite possibly selected the perfect place to bed down for the day; their resting spot was a shelf approximately 30 yards wide with a sheer cliff behind them and a few smaller cliffs below. I only had one point I could access the goats without being spotted, and that was through a chute off to their left. If I circled back out to my right, I could climb through the scree, up the chute and pop out slightly behind where the goats were bedded. With only the rest of the afternoon and the next morning left to hunt, I knew this was probably going to be my final chance to fill my tag.

I descended as quickly and quietly as possible to get below their line of sight. I had picked what I thought would be the easiest route to reach the chute and started the climb, being careful to stay hidden. Each step I took seemed to take me backwards as the scree slid further down the slope, generating mini rock slides that, at the time, sounded to me as loud as gunfire. In retrospect, I’m sure the decibel level was barely noticeable to a goat that lives almost daily with rockslides and avalanches. As I reached the chute an hour and a half later, my throat began to tighten with anticipation.

I calculated that I was still 300 feet below them, so I dropped my pack to make the climb a little easier. The boulders in the chute were astonishing; some were the size of a backpack and some could cover up a car. In the intertwining jumble of rock, the footing seemed solid but I still did not trust them to stay in place as I climbed, so I adopted a rule: that I would always have at least three points of contact. I methodically set each step with care, testing each boulder before committing to it with my weight. In this manner, it took another 45 minutes to close the last stretch.

When I reached where I thought I needed to be to emerge behind the goats, there was a 10-foot cliff out of the chute that I needed to scale. My heart was racing as I slowly crept up the face; I was absolutely positive that I would soon be notching out a tag. I slowly, slowly raised myself up to peek above the edge, when the thin ledge I was standing on gave way! I helplessly slid down the face, back into the chute, dislodging rocks and landing on a two-foot boulder — but thankfully still on my feet. I felt the boulder start to roll and I jumped further up the chute to another rock as the one I had been standing on tipped over and gathered momentum. As it clattered and banged down the chute, it gained speed and jarred others loose in its path. I was certain that at any minute the entire chute would be ripped loose and scream down toward the valley floor with me in the middle of it all, but luck was with me again as it stayed in place.

The feeling that was coursing through me was a mixture of elation and nausea. I was ecstatic the contents of the chute had held, but almost shaking from the fright of how lucky I had just been. As I regained my faculties, I remembered why I was there in the first place and my thoughts returned to the goats. I did a quick check of my bow to make sure I hadn’t broken anything and slipped up the chute a little further to climb out in a spot that appeared a little more stable. I again slowly peered over the edge to get a range on the distance to the goats but it was in vain. The goats had vanished from the shelf and my season was over.

I have spent a lot of time reflecting on this hunt, and for the first few months after the season ended I felt bitter for not harvesting a goat and for — in my eyes — failing. I thought about the many different ways I could have I approached this hunt. Of course, the first obvious deduction is that I could have picked a different week to go on the horseback expedition. A week before or after would have made a huge difference as the skies were clear both weeks. Instead, we spent half the week holed up in the tent trying to stay dry instead of hunting, which also leads to another glaring problem with the hunt: lack of proper equipment. If I would have had the proper gear to access the basin I had originally intended, I truly believe I would have tagged a billy. If the weather had stayed nice, it probably would have negated that need to a certain degree, but the ice-covered slopes made it simply too dangerous to tempt fate without an ice axe or crampons.

While I am disappointed I didn’t punch my tag, I can’t honestly say that I regret anything either. My Dad and I put together a horseback, backcountry hunt that we probably wouldn’t have done if not for this tag. We had a great time, even with the hardships, and we created memories that will last forever. I know he felt bad when the horse went down on his leg and he harbored some guilt that the hunt didn’t go as well because of this, but to me, any guilt or regret was unfounded as it just added to the experience we had.

When I set out on my solo hunts for the last few trips, I spent days without seeing or hearing another human, and that is without question the best way to partake in the wilderness. I had incredible adventures that very few will ever get to experience and I believe I learned more about myself in that couple of weeks than I probably had in the couple of years prior. The lessons I learned will be invaluable the next time I draw this tag. As I slowly came to terms with the shortcomings of the hunt, I came upon a quote by Theodore Roosevelt that helped to put the failings into context: “It is hard to fail, but it is worse never to have tried to succeed.”

THIS SUBSCRIBER STORY IS BROUGHT TO YOU BY MYSTERY RANCH