Allow me to paint a picture for you.

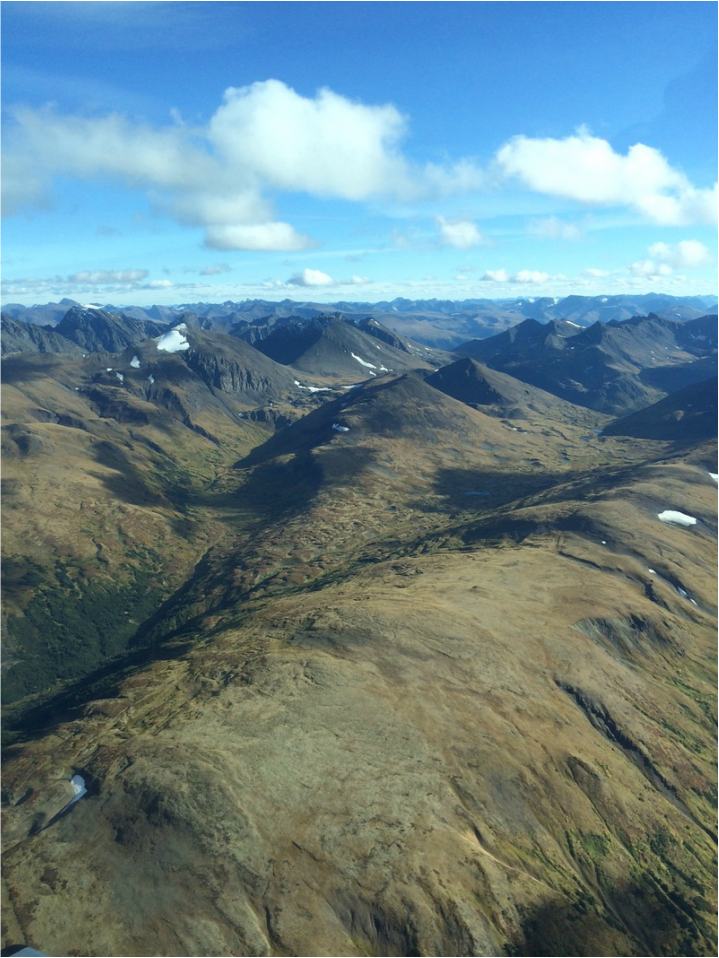

After a twenty plus hour drive followed by a long jetboat ride into some of the most remote country in Northern BC we were exhausted. We arrived at what would be base camp for the week with just enough light to set-up our tents, start a fire, and have dinner and a couple of single malts before heading to our tents for the night.

We set an alarm and quickly drifted off to sleep but the alarm turned out to be entirely unnecessary.

We were awoken by a bugle echoing out of the darkness of the small, tight river valley and into camp before the alarm went off. A sound so haunting yet so mesmerizing I will never forget it. We scrambled out of our sleeping bags, with grins wide enough to pass as doubles for the Cheshire Cat. Our plan for the morning was to hunt our way up the small tributary we were camped at the mouth of, get a lay of the land and scout possible spike camp locations before returning to base camp for lunch and a planning session. The fog hung thick and low on the Muskwa River, and rather than blindly stumble our way by headlamp up the smaller river we let the sun rise high enough to burn off some of the fog before leaving camp. It was a perfect mid-September morning in the North Country.

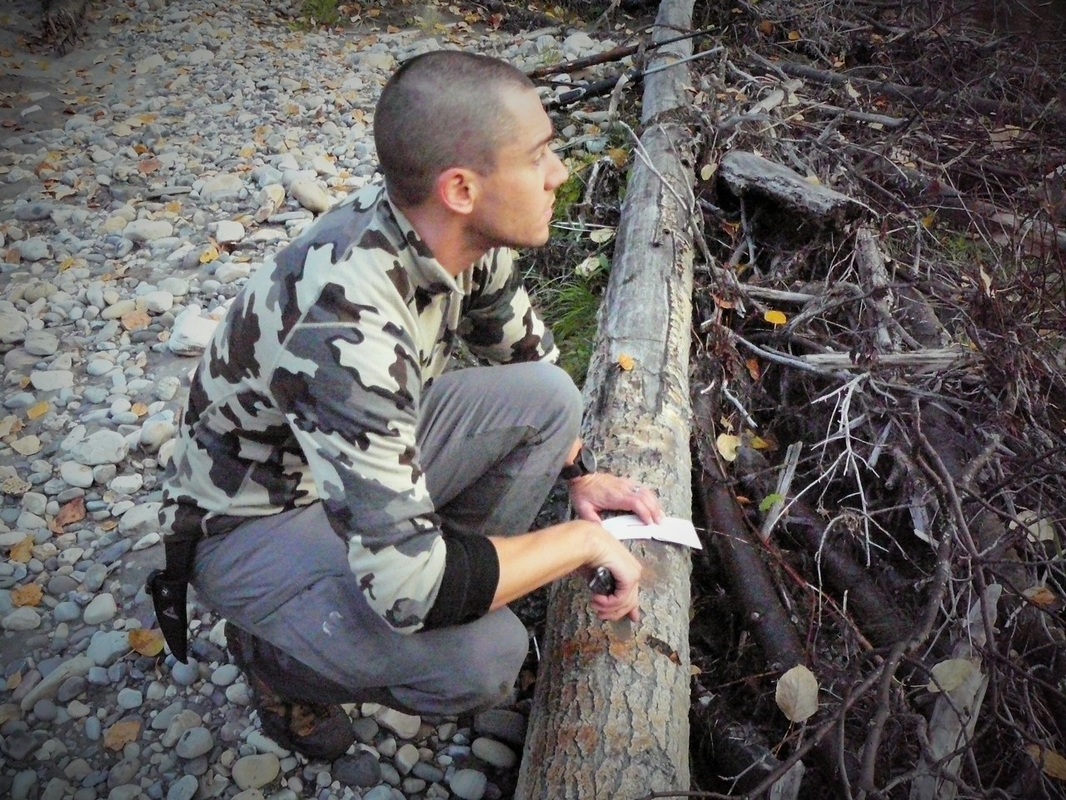

We still hunted our way along the river bottom, cow calling from time to time, absolutely enthralled by the scene before us. There were tracks and fresh droppings everywhere, the wind was holding dead steady in our faces, the aspens and willows had just started to turn and the impossibly steep river banks rose hundreds of feet above us on either side of the winding, gin clear river. After roughly three hours we reached a large fork in the stream and decided to take a quick break and have a snack before heading back to base camp. I set my pack and rifle down against a log, took a seat and soaked in the environment. The sound of the river rushing over the rocks, coupled with the knowledge we were the only two hunters to have been up this tributary in years brought a smile to my face.

And in that exact moment, we heard the unmistakable sound of hooves on river rocks.

And that’s when what scientists call a flow state kicked in. Everything happened unbelievably fast yet time seemed to stand still. To this day I don’t remember grabbing my rifle, jumping over the log and running into the river. Pure instinct took over. I found myself running through the thigh deep water like it wasn’t there, eyes up and searching for the elk that made the sound, paying no attention to my footing yet in total control of my body…there was no emotion just total focus on the task at hand. And there he stood in mid-river in the far branch of the fork.

The memory is literally seared in my brain. He was seventy yards away, slightly quartered towards me, looking straight on. By this point, I’d made it through the deeper channel and onto a small island of dry rocks and the instant I saw him, he saw me and I dropped to a knee, rifle up and crosshairs on his vitals all in one completely fluid, effortless movement. I was one with the gun and one with my body. Water dripped off his mane from the river water he’d just been drinking, his dark, thick antlers spreading regally behind him with impossibly white tips by comparison, so typical of our Northern BC bulls. Time literally stood still. I had him dead to rights in my scope but I needed to confirm 6 points before I could take the shot. I can remember counting, and re-counting his tines, whispering to myself “give me six, give me six, give me six” while my heart pounded like a sledgehammer in my ears but I couldn’t tell for certain while he was looking straight at me.

I tried to melt my body into the river rocks I was kneeled on, hoping he’d disregard this weird creature that had run into the river, disturbing his morning only to disappear in the rocks halfway across. And that’s when he turned broadside, the sixth point I was so desperately hoping for glinting in the sun that had just risen above the riverbanks at my back. The gun went off without me even consciously acknowledging “pull the trigger”, again everything was happening in a state so fluid and Zen-like that my brain and body were operating at a speed and connectivity I didn’t even know was possible. He dropped at the shot, and within minutes had breathed his last breath.

I have no doubts many of you reading this could recount very similar experiences.

That was three years ago. He turned out to be a 7×6 315+ inch bull, a true monarch of the North and a bull I’m unlikely to top here in BC in my lifetime. But the score is a mere statistic, a bonus, nothing more. Was I ecstatic to take such a fantastic, mature animal? Of course. Did I thoroughly enjoy the elk steaks and roasts I brought home to family and friends? Absolutely. But the experience and memory I just shared is the only true trophy I really need. To this day I can remember that feeling like it was moments ago, indeed while writing this article goosebumps ran up and down my arms and chills of excitement coursed through my veins. It was like I was there again.

And that is the unbelievably raw power of flow.

The concept of a flow state is not new. Researchers from the fields of psychology, neuroscience and psychiatry have been studying this phenomenon for more than a century. But it was not until Steven Kotler published his seminal book The Rise of Superman that flow and flow states gained mainstream attention and more importantly made flow accessible and attainable to anyone. In his book, Kotler uses examples from action and adventure sports to outline what exactly flow is, where it comes from in the brain, what it’s made from neurochemically speaking and the typical “triggers” or conditions within which a flow state is most likely to arise. Extreme athletes like big wave surfers, BASE jumpers, free soloing climbers and big mountain skiers have “hacked” this state quite simply because both their lives and their livelihoods depend on it. If you have even a passing interest in performance, both mental and physical, this is without question one of the most important books written in years.

Kotler writes:

“Most of us have at least passing familiarity with flow. If you’ve ever lost an afternoon to a great conversation or gotten so involved in a work project that all else is forgotten, then you’ve tasted the experience. In flow we are so focused on the task at hand that everything else falls away. Action and awareness merge. Time flies. Self vanishes. Performance goes through the roof. We call this experience flow because that is the sensation conferred. In flow, every action, each decision, leads effortlessly, fluidly, seamlessly to the next. It’s high-speed problem solving; it’s being swept away by the river of ultimate performance…it is an optimal state of consciousness, a peak state where we both feel our best and perform our best. It is a transformation available to anyone, anywhere, provided that certain conditions are met…flow is an extremely potent neurochemical response to external events and requires an extraordinary set of signals.”

Quite simply, the neurochemicals present during flow represent one of the most potent performance and mood enhancing cocktails our brains and bodies can produce. Flow is such a heightened state of being, that some researchers have even started to (half) jokingly refer to it as the meaning of life.

The book goes deep on all aspects of flow and flow states and is a truly enthralling read, but it was in his descriptions of the external conditions required for flow, what he refers to as the external triggers that it dawned on me.

Flow is why I hunt, and I would hazard why many of us hunt. I just didn’t know it.

There are three environmental or external triggers he outlines as conditions for flow: risk, a rich environment and what he calls deep embodiment. From a hunting perspective, risk is self-explanatory. Flying, hiking or packing into the wilds of the mountains, where most humans dare to tread, braving harsh, unpredictable environments may not be the same as surfing a giant wave but it certainly is not for the faint of heart. The second external condition, a rich environment, is where hunting in particular shines. Kotler defines a rich environment as “a combination platter of novelty, unpredictability and complexity – three elements that catch and hold our attention much like risk.” What are the mountains and animals that inhabit them if not unpredictable and complex? And the last trigger, deep embodiment is a form of full-body awareness, a heightened sense of control, coordination and awareness where your brain and your body are connected and communicating at a speed you never knew was even possible. My story in the introduction highlights this exact phenomenon in a hunting scenario.

Having read this book, I can now say without hesitation that flow is why I hunt. Not for the meat, not for the trophy but for the unbelievably addictive and raw, optimal state of consciousness hunting brings out of me when everything comes together. And is that not the key point here? At times hunting is far from enjoyable. We’ve all spent days huddled in a tent, socked in by rain. Or more hours than any sane human should endure freezing in a ground blind or treestand. And dedicated months of planning, preparation and significant expenses, all to come home with “nothing”. And yet we keep going back. Hiking deeper, climbing higher, and pushing ourselves further than we ever thought possible, all for those rare moments when we are “swept away by the river of ultimate performance”.

Adam Janke

Editor in Chief