The North Fork of the MacMillan varies in width from seventy-five to two hundred feet. The current races in numerous rapids around sharp curves, from five to eight miles an hour, often along wide bars, and the banks are full of driftwood, piled high in many places, causing great difficulty in taking canoes around it. This Fork resembles a mountain torrent more than the ordinary river of the territory. We were obliged to tow the canoes as far as we went, making use of paddles only for crossing, and poles only to go around driftwood. The country on the right—between the Forks—consists of low, rolling ridges; on the left, it rises gradually to the Russell Mountains, which were then white with snow that had fallen the night before. That snow did not melt again before the following spring.

After going three miles we made camp in the spruce woods, where red squirrels were very abundant, chattering on all sides. Selous took his rifle and wandered for a short distance up the river while I went back in the woods. We returned later, and sat before the fire, rejoicing to be separated from a crowd, so that we could realize a more genuine wilderness charm as we watched the sparks of the fire shooting up through the spruce trees, and heard the splashing of the river as it raced around the banks and glided over its rocky bottom.

September 2

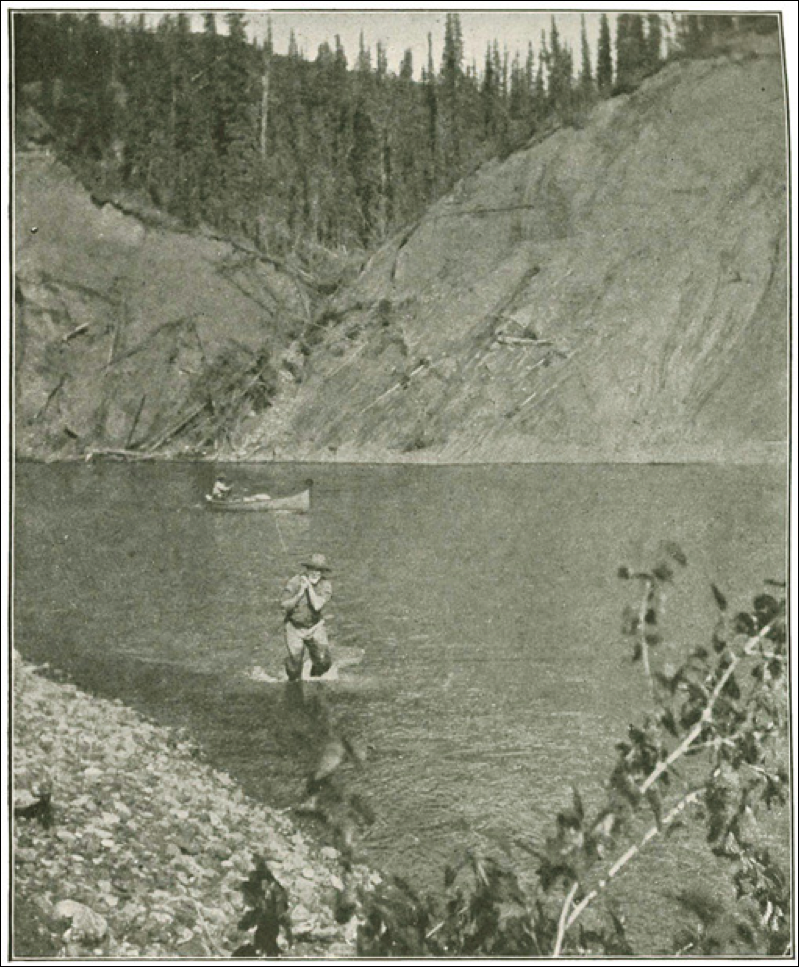

The next day we towed the boats, each of us doing a share of work indifferently with our men, until noon, when we stopped to make tea and eat lunch. With ropes over our shoulders, we took turns at the heavy pulling, walking on the bars, wading in the icy cold water, toiling around driftwood, crossing from one side of the river to the other, and continually straining to drag the boats up the riffles. It was very hard work and progress was slow. The river ran between ridges which were mostly covered with black spruce and poplars, though here and there white birches appeared. The poplars and birches, tinted with fall colors, brightened the wildness of the landscape. On the bars, numerous tracks of bears attested their annual feasting on salmon, an abundance of which had died before our arrival. Moose tracks, most of them old, were also abundant.

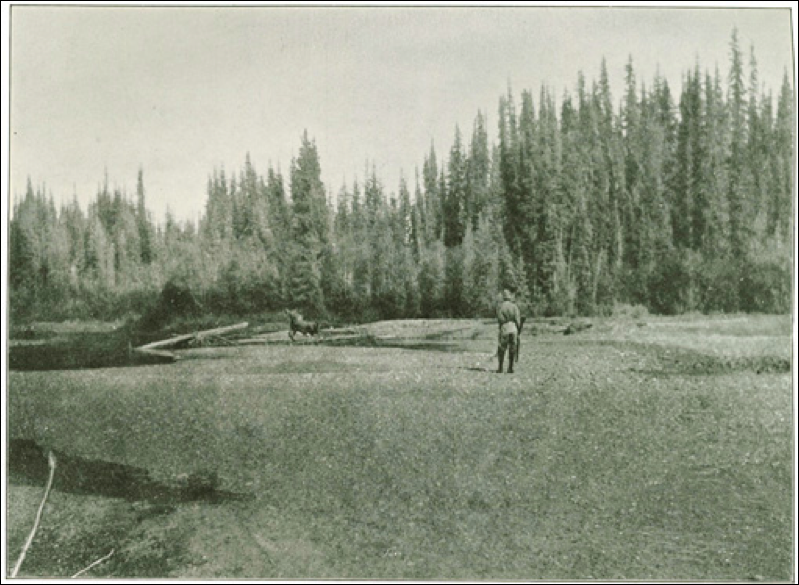

Selous and the calf moose, September 2.

Selous and the calf moose, September 2.

Not long after we had lunched, as Selous and I were hauling the canoes, Louis saw a cow moose and her calf well ahead on the other side of the river, and about to cross. Selous, who was ahead, quickly took his rifle from the canoe and crept forward, while we crouched to the ground. As they waded the river, he circled around some driftwood, waded a slough, and shot the cow just as she was about to enter the woods. She staggered back toward the river and fell dead in a slough. As he signaled that she had fallen, I ran forward to follow him. The calf, trotting about in perplexity, suddenly saw him and coming directly toward him stopped to look at him, the hair on its fore-shoulders erect and bristling. Running back, I took my Kodak from the boat and returned in time to take a photograph, including both Selous and the calf, which was by that time trotting toward the woods. The wind was blowing directly from him to the calf.

The others then came forward, and the moose was dragged up on the bank and dressed. Here was meat for the first time in several days, and we camped there to enjoy the feast. Selous taught me a new delicacy, the udder, which was cut out and boiled for several hours until soft and tender. The next morning it was sliced, rolled in flour, and fried. It proved to be delicious, the choicest morsel of the animal. The same is true, as I learned later, of the udders of sheep, caribou, and deer.

While dressing the moose a small black gnat, slightly larger than the midge of Eastern Canada, swarmed about us and its bite was particularly annoying. The small gnats begin to be troublesome all over the northern country about the middle of August, after most of the mosquitoes are gone, and continue until well into September. They usually are found close to running water, but are seldom seen above timber-line.

We took our rifles and went out for the remainder of the day, Selous going up the bars, while I went back on the ridges between the Forks. I followed a brook through dense spruces, swamps, and deep sphagnum moss, to the top of a ridge. High up on these ridges I found well-beaten moose trails, usually running parallel with the river; in some places, they were worn three or four feet through the moss and soft ground to the roots of the spruce trees. These trails are well-defined routes of moose travel, and though intersected by others which are less deeply worn, they parallel all the rivers and often the smaller streams. The country was completely covered with timber and very broken, the slopes of the ridges often very steep; and numerous brooks rising from springs or small lakes farther back fell through small canons. There was little sign of game outside of the moose trails; birds were very scarce, but rabbits and red squirrels abundant. Such is the character of the country between the forks until well up the river near the mountain ranges.

Returning I found a cheerful camp-fire, and after gorging with meat, we chatted awhile before sleeping. Suddenly, a short wailing cry sounded from the dark woods not far distant. It was made by the calf, and we both felt glad that it was old enough to take care of itself, after the loss of its mother. We did not hear it again, and slept in the cold, crisp air under the shining stars.

September 3

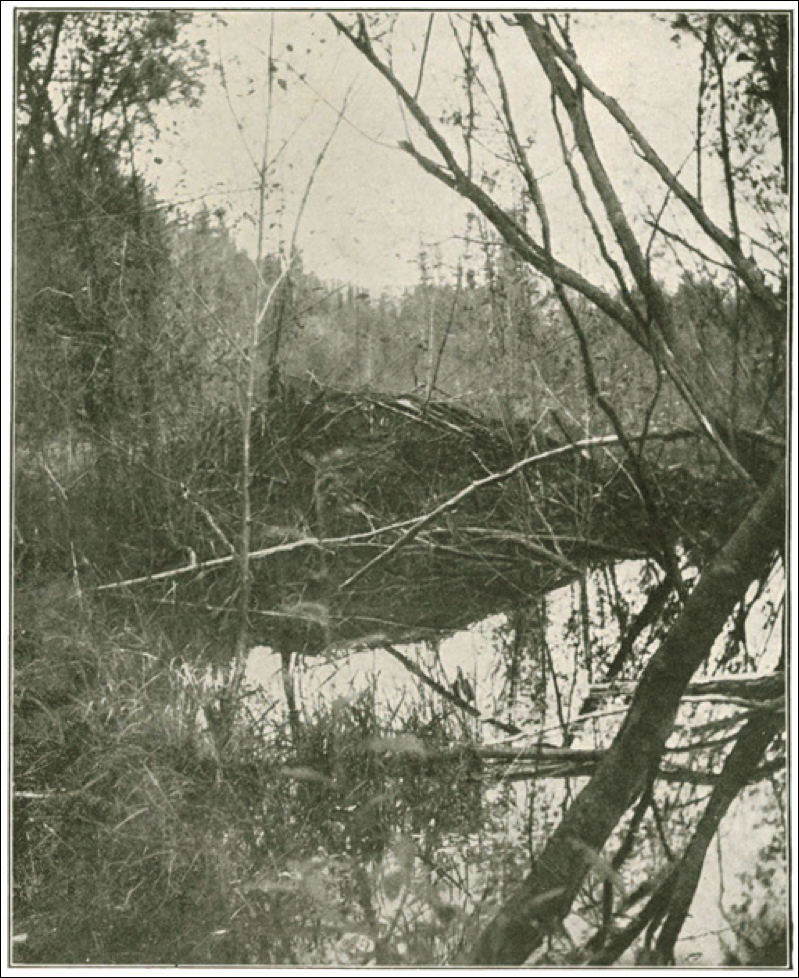

The next day was one of continuous towing in shallow water against a swifter current; the driftwood increasing; the river curving more frequently. At one point, near a high escarped bank, where the river bends sharply to the south, we found a large beaver dam, constructed across the mouth of a creek-channel, made by the escape of a small volume of water around a bar some distance above. Behind it, were acres of water, flooding willows, alders, and poplars, and not far back a family of beavers occupied a large house in three or four feet of water, surrounded by high poplars and willows. Selous and I waded to it and after examining it with interest I took some photographs of it.

We made camp late in the afternoon near a flat swamp covered with willows, alders, dwarf birch, and strewn with burnt timber. After tramping about in it, Selous returned and reported more fresh moose signs than we had seen at any point along the river. Here we first had a glimpse of the Selwyn range of mountains, rising ahead in majestic peaks and offering encouragement for a better game country.

As we were sitting about the fire fifty feet away from the bank, in a dense thicket of woods, Louis suddenly heard a bull moose walking on a bar on the opposite side of the river. It was several degrees below frost and Selous, though without trousers or shoes, took his rifle and followed by Louis and myself picked his way in the dark through the thick, tangled woods to the bank of the river. But the moose had entered the poplars and Louis in vain tried to entice it out by calling with a birch-bark horn.

September 4

In the morning, a cold stiff head-wind chilled us and continued all day, as we plodded on under conditions constantly becoming more difficult; and we were disappointed not to see the mountains ahead, which were covered with clouds. We finally arrived at Barr Creek, where two trappers, Jack Barr and Crosby, had been trapping the previous winter. We had seen a flock of mergansers that day—the first ducks observed on the North branch. Few birds of any kind had been noticed, except an occasional hawk floating through the air or sitting on a dead tree.

We pitched camp in a delightful spot in heavy spruce woods, and Selous, as usual, went up the river to prospect for game. I had each day set out traps for small mammals, but without success. In front of camp, across the river, were wide bars covered with willows, poplars, and alders, all glowing with a rich fall color. The river, swift and deep, fairly roared as it swirled around a huge pile of driftwood and beat against the banks.

September 5

It was snowing when we started; the wind continued, and it was freezing in the afternoon, but the travelling was a little better because of more bars and less driftwood. It was gloomy work; all the hills and ridges covered with thick clouds so we could see nothing of the country ahead. At three in the afternoon, when I came around a curve while Selous was a few hundred yards ahead, I saw a large black bear, feeding high on the slope of a ridge which extended parallel with the river. Attracting Selous’s attention I hastened forward and urged him to go after it since he had never before seen a wild bear in the wilderness. Coghlan, Louis, and I tied the canoes to the bank, and watched the stalk, all of which could be plainly seen from where we stood on the bank of the river. On the slopes of the ridge were many clear areas, which had been given a reddish appearance by dwarf birch and huckleberry bushes, then colored by the frost. It was in one of these clear spaces that the bear was feeding.

At intervals, between them, strips of dense timber and undergrowth, several hundred feet wide, extended down to the river. Selous started upward in a circle, and soon we saw him climbing the ridge in one of the clearings, where there was but one strip of timber between him and the bear, which continued to feed, gradually approaching the timber. Having marked well the spot where he had last seen the bear, he arrived at a point exactly opposite it and started directly toward the timber. His approach was then against the wind and he cautiously and slowly went forward. Through my glasses, I could plainly see the bear as it approached the woods, directly in line with Selous’s advance, its glossy black coat reflecting the sunlight, which at times caused it to appear very large. Both Selous and the bear entered the timber at the same time, apparently approaching directly toward each other, and momentarily I expected to hear a shot. Soon we saw Selous emerge a little above where the bear had entered, and proceed with caution, carefully looking about. We knew that he had not seen the bear.

Afterward, I learned that the timber was filled with small spruces, alders, and dwarf birch, so he could see only a few feet in any direction. But he must have gone through noiselessly and with skill, passing the bear within a hundred feet or so, for shortly after he appeared, the bear came out a little below the point where Selous had entered the timber, and continued travelling in the opposite direction, still feeding, and wholly unconscious of its lucky escape. It fed along indifferently until it reached the trail which Selous had made when ascending. Then it suddenly threw up its head, gave a great jump, and running with speed down the ridge disappeared in the timber.

Once before, in Mexico, I had seen a similar action on the part of a grizzly bear when it crossed the fresh trail of a man, and it was extremely interesting thus to witness a second case. Selous, still looking for the bear, had passed out of sight along the ridge. When the bear began to run, I immediately crossed the river, and, in my efforts to hurry in the direction it had taken, almost bogged myself in a slough. I could not find a trace of it and returned. Selous came in later, after we had made camp, thoroughly perplexed at not having seen the bear at all. Though an excellent stalk was frustrated by such bad luck, the sight of game was stimulating and made us eager to advance, particularly since our goal was then not very far ahead.

September 6

We had undertaken to go up the North Branch without any knowledge of the country, so it was necessary for us to explore for a good place to find game. The next day was the most trying one of our trip up the North Branch. It was cold, cloudy, windy, and wintry. The river was narrower and more tortuous; its banks were continually lined with driftwood and bordered by ice; the current was swifter, and often the water was so shallow that we had difficulty in towing the canoes without unloading them.

Until late in the afternoon we worked while hands, legs, and feet were numb with cold. At a point where the river bends to the north and finds its course between high mountain ranges, not far below Husky Dog Creek, we decided to stop and make a reconnaissance with a view to locating a camp at timber-line, high on the ranges to the south. It was so misty that we could not see the mountains, and soon snow began to fall and continued, more or less, all night. It was dark at 7:30.

September 7

In the morning three or four inches of snow covered the ground, and snow continued to fall at intervals all day. Selous soon started to investigate moose signs on the flats, while I directed my course toward the mountains, hoping to find a good place near timber-line to make a camp, and a good route up the slopes, since we were obliged to carry our equipment and provisions on our backs.

South of the river, a hundred feet from the bank, is a terrace thirty or forty feet high which extends north, parallel with the river for many miles. The country behind it, both flat and rolling, extends two miles to the foot of the mountains. This broad, level country, all burnt over, was covered with moss, brush, huckleberry bushes, and cranberries, and strewn with tangled logs. Swampy in places, it is dotted with small lakes, and the standing burnt trees scattered through it give an aspect of grim desolation. Old moose tracks were everywhere, and well-cut trails parallel with the river were frequent. While passing through it I saw several flocks of migrating robins, a grouse, some hawk owls, and many Alaska jays and red squirrels. But no other animals were observed during the rest of the day, and the fresh snow disclosed no tracks of any kind, except those of red squirrels.

I climbed the lower ridges, ascended the mountains to timber-line, and followed along the side of a deep ravine, through which a fair-sized brook, cutting in some places deep canons, came down from a rather broad valley, between high, rough mountains. This valley, gently rising, was enclosed in an amphitheater of rugged mountains, rising abruptly to high peaks and jagged crests glistening in the snow. All through the northern country such places are called draws, signifying, I think, a suitable conformation of the land to “draw” the water from the adjacent mountain slopes. At the heads of each of these draws above timber, there is usually an area, level or gently sloping, covered with dwarf birch, willow, and alder, all extending well up the adjacent slopes. The ground is boggy, and the abundant willow growth provides the favorite food of the moose in fall and winter. Everywhere at the head of a draw old moose tracks were so abundant that the place looked like a cow pasture, and as many tracks were observed among the willows of the higher slopes as in the area below. A well-defined moose trail always runs on each side of the creeks which flow from the draws, and the trail often leads over low saddles between the ranges to the head of another draw.

I chose a place for a camp close to the brook, near the end of timber, in a location suitable for climbing the mountains on either side. The mountains were then so covered with mist that I could not use my field-glasses to find likely places for sheep. On returning I learned that Selous had seen no fresh signs of any kind. Our limited time, the difficulty of climbing the mountains covered with light snow, our ignorance of the country, and the lack of game seen up to that time, did not look encouraging; and since the snow continued to fall, we felt some anxiety as to the ultimate success of our trip.

September 8

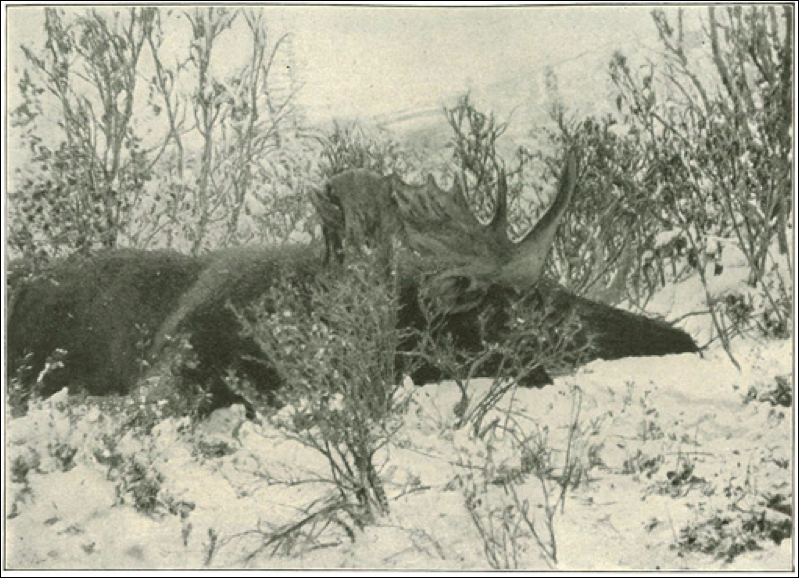

Snow was falling when we rose, but it was a wet snow and not likely to continue all day; we therefore decided to start. A cache was made by suspending some poles about ten feet up between trees, and on it were placed the provisions and materials we could not carry. These caches are always necessary, as otherwise provisions might be taken by bears, wolverines, or wolves. Packs were made up and, putting them on our backs, we started about noon, crossed the flat, and while climbing the ridges were soaked to the skin from the wet snow suspended on the brush. This caused us to become chilled as we toiled upward with aching backs through deep snow and thick undergrowth. The mountains, covered with mist, could not be seen. Late in the afternoon, as we were walking on the slope near the upper flat of the draw, Louis, who was ahead, saw a bull moose feeding in the willow brush some seven or eight hundred yards below, near the brook. Selous, who was following Louis, immediately started to find an approach to it, and concealed as we were behind some low spruces, we had the pleasure of watching the whole stalk.

For a few moments, I watched the moose as he was standing and feeding, but as I turned my head to note Selous’s course, the bull apparently disappeared, and Louis whispered that he had lain down. I looked carefully through my field-glasses, but he blended so perfectly with the willows and alders that he was not visible. Finally, as he moved his head, I could make out the tops of his horns, then hardly distinguishable from the brush because of the strips of velvet still hanging on them.

We waited with keen interest for Selous to come in sight. He had started in a circular course to approach the moose against the wind, which was blowing up the brook. He finally appeared and began to approach with the utmost caution, advancing in a straight line toward the exact spot where the moose was resting. Selous was too experienced to have neglected to mark a tall tree near which the moose was standing when he started, so that he could find the place after circling through the woods. Finally, coming nearer, he advanced step by step to within thirty feet and stood looking. Louis whispered: “Now you see moose jump and run!” But I saw Selous approach a few steps, bend forward, put up his rifle and fire. He immediately shouted, and knowing the moose was dead we hurried to the spot. Selous had suspected that the moose was lying down, and at last had seen the tips of its horns. A step or two nearer brought the head and neck of the unsuspecting bull in sight, and the bullet was delivered at the base of the brain. It was a large old bull, with broad, flat horns, well palmated, spreading fifty-seven inches—an unusually fine trophy.

That was our introduction to a camp soon made near the carcass. We had brought only a large piece of canvas, and when poles had been cut and inclined against a cross-pole, it was thrown over them. Spruce bows were strewn beneath it and the shelter was complete. A big fire was started; the packs were opened; their contents arranged in order under the shelter, and after feasting on fresh meat we sat in front of the fire that night feeling more cheerful than at any time since leaving Dawson. We were at last camped high up among the mountains, a fine trophy was in our possession, and we slept soundly after enjoying the dim picture of the rugged mountain in front, its peak, viewed through the spark-spangled smoke of the fire, towering high above like a huge white spectre. The mercury responded to the higher elevation by descending to sixteen degrees Fahrenheit above zero, the lowest recorded up to that time.

September 9

It was snowing the next morning, but cleared soon after I started to climb the ridge north of camp and ascend the high mountains beyond. Selous remained in camp to prepare his trophy. The snow on the low spruces and dwarf birches gave a true wintry aspect to the landscape. Up to that time I had not convinced myself that leather moccasins were a failure for walking in the snow, but during the ascent of a steep slope, covered with five inches of snow, I soon realized it. Slipping and often falling, it was next to impossible to climb, but finally I reached the top. The sky was perfectly clear and for the first time I beheld the landscape of the Selwyn ranges.

They are entirely different from the Ogilvie Rockies. Instead of a series of parallel ranges, the Selwyns consist of irregular groups of mountains, often isolated by wide valleys, the summits from six to eight thousand feet above sea level. The sculpturing of the granite is bold, rugged, and massive, the shattered pinnacled crests forming an imposing sky-line. Timber-line is between three and four thousand feet above sea level.

Looking below over the vast area of burnt ground, wild and desolate, I could see the river continually curving in its course. Beyond it were two high mountain ranges which did not obstruct a view of the sharp peaks and broken crests of the Russell Mountains. Toward the south-west were the lower ridges and timbered country, including the area between the Forks; and directly south were valleys and woods, extending several miles to a lofty plateau-shaped mountain, its broad dome deceiving the eye as to its altitude. Looking up the river, the vision was lost in a horizon of mountains and peaks, some misty and dim, others glittering in the paths of sunlight where ever it broke through the clouds.

The valley above camp was characteristic—a broad area surrounded by an amphitheatre of the highest peaks, rising above shaggy crests and often above vast precipices. Below the highest peak, almost suspended at the foot of a great cliff high on the mountain-side, the protruding slope held a beautiful little lake covered with clear, silvery ice, which reflected the crags and peaks above it. A little farther on, along the same range, but still higher up, was another lake set in almost perpendicular walls of granite, which surrounded it on three sides. The whole country was covered with snow and seemed bleak and inhospitable.

As I looked over the small lake a golden eagle was soaring along the cliffs, rising now and then to the crest, and, after circling over the peaks, again descended until it floated across the valley to the higher summits beyond. Here and there I heard the whistling chatter of a ground squirrel still defying the snow and cold before retiring into its hole to sleep. I wandered about the mountain top and along the crest, hopelessly unable to make much progress because of my slippery moccasins, without seeing tracks or signs of sheep, and at times, when the sun shone through the clouds and mist, almost blinded by the glare of the fresh snow. I returned to camp at dark, somewhat discouraged by the difficulty of ranging over mountains covered with light snow which was not deep enough to provide a foothold. Besides, many of the slopes were so icy that in any case much distance could not be covered in the short hours of daylight.

You’ll be pleasantly surprised by the high-quality photographs and drawings from decades long gone that are scattered throughout these titles. This series includes books by renowned adventure authors such as Theodore Roosevelt, William T. Hornaday, Charles Sheldon, and Frederick C. Selous, to mention only a few. Available online at:

www.historyofhunting.com

www.boone-crockett.org