The world is full of one-eyed travelers. One of the strange things about such mountains as those of British Columbia is the wide variation between the impressions which they produce upon different people. I know a miner and prospector to whom the finest mountain-range is merely a place in which to look for signs of ore. There are sportsmen who see nothing in mountains save what appears over the sights of their rifles. There are photographers who see nature only as it is revealed in their “finder,” “stopped down to aperture No. 32, one-twenty-fifth of a second exposure.”

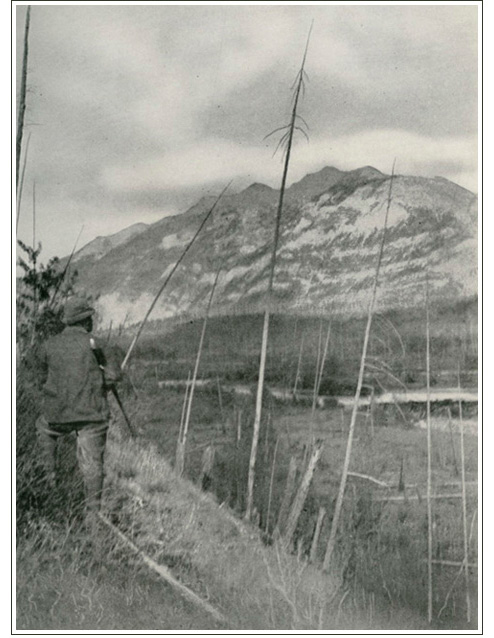

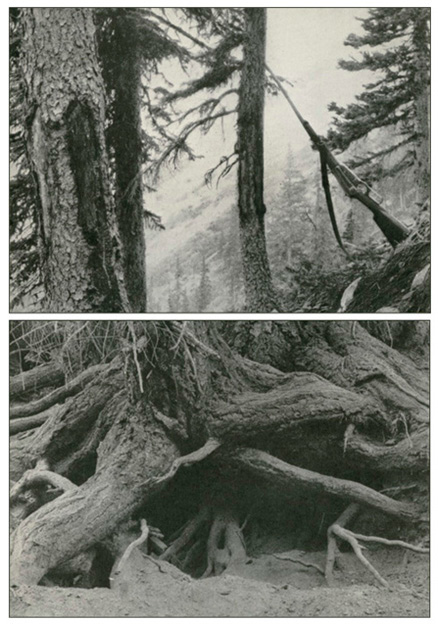

The Author’s Colleague and Guide

The Author’s Colleague and Guide

Before me at this moment there lies a book about mountains; but it is only a book of heights and depths, scaled or to be scaled. Its author was blind to the glories of mountain vegetation, and to the ever-interesting mammal and bird fauna of the steeps. The works and ways of Nature at timber-line held absolutely nothing of special interest to him, save as they furnished things to climb over. He was interested in forests only as they burned, and their smoke obscured the view of summits to be climbed. In a volume of more than four hundred pages the author devotes half a page to the flora of a magnificent domain of mountains, and three pages to their animal life! Really, is it not strange?

Often when in the tropics I lamented my lack of botanical knowledge, but not half so much as I deplored it in the Columbian Rockies. To pass over twice in one day the uppermost limits of perhaps fifty species of plants and trees, and know of them so very little, was at times really depressing. Each of the few species which I did recognize was as welcome as the face of a friend at a crowded reception.

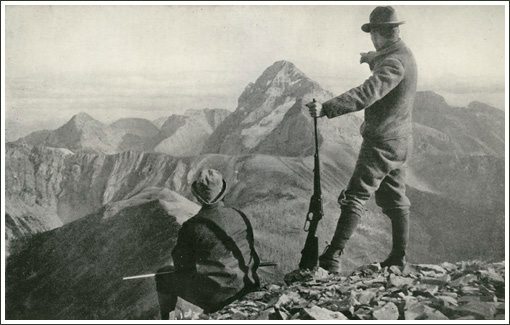

To me, Charlie Smith was truly a guide, philosopher and friend, and at all times a source of intellectual comfort. He loves the mountains so well that no money consideration can tempt him to leave them. He loves them in storm or in calm, amid the terrors of winter as well as the delights of spring, summer and fall. Once while resting on a lofty summit, with a magnificent panorama spread out at our feet, and stretching away to the Continental Divide, he said to me:

“I have had chances to go into business, and in some of them I am sure I could have made money. Possibly I could have become moderately rich. But what would all the money of a millionaire be to me if it took me away from the mountains that I love? No amount of money in a business office could make up to me what I would lose in giving up this country. No rich man can get out of his money more satisfaction in life than I find in these mountains; and here I mean to stay until I die.”

Charlie is a strange, and even remarkable, combination. He loves steep mountains like another Whymper, and is a very bold and level-headed climber. He loves all animal life, and is not only a keen observer, but his accuracy in observing is grateful and comforting. He loves tree-life and plant-life with the taste of a born botanist. He is a fine hunter and trapper, brave, but sensibly cautious on the trail, and completely free from the boastful and intolerant vein which spoils many a good woodsman. Like most of the mountain men whom I have known intimately, he is clean-minded and high-minded, and as a narrator and describer I have never among frontiersmen known his equal. When he tells a story, he makes you see it as in a moving picture; and he writes with wonderful ease.

I urged Charlie to write out the fascinating stories of adventure and chapters of wild-animal lore that he gradually unfolded to me, and offer them to the magazines which are always on the lookout to discover new and fresh springs of literary refreshment. At first he felt that he “could not write well enough”; but as a matter of conscience and duty, both to him and the public, I urged him until he took courage, and decided to try.

The foregoing “appreciation” is in no sense a digression, for Charlie Smith was far more interesting and noteworthy than any of the mountains up which he led me.

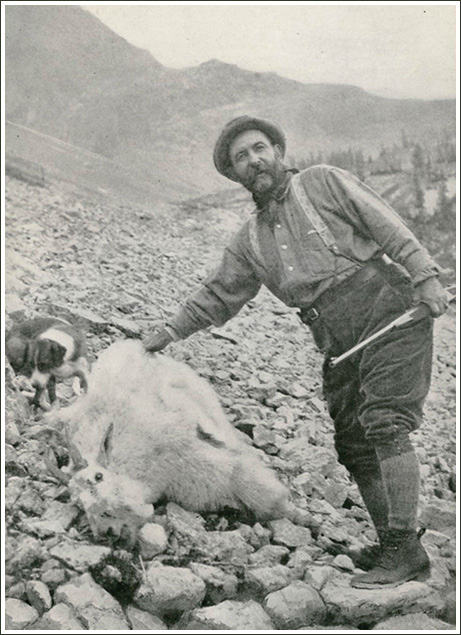

Every sportsman knows that the occasions where four men can profitably hunt together are few and far between. Mr. Phillips usually went out with Mack Norboe. John Norboe made various special scouting trips for the general welfare, and Charlie Smith and I worked together. After the great day with goats, on Phillips Peak, we devoted our energies to hunting for grizzly bears; and in quest of them we went into all sorts of places. Immediately after camping in Avalanche Valley, our first care was to hunt down the valley, through the ribbon of green timber, six miles or so straight away to the base of Roth Mountain; and although we found about a dozen or fifteen rubbing-trees, where bears had stood up to scratch their backs, we saw no bears.

Continuously we watched the open ground of the “slides” for bears feeding; and as often as we could manage it, we climbed to some new summit, in order to view a new basin, new rock walls, more slides, and more new country far beyond. In such a region as that is, to hunt is to climb; and to climb is usually to go above timber-line before you stop.

I was frequently surprised by the differences between mountain sides and summits that one would naturally expect to find alike. Take False Notch, for instance, about two miles above Camp Hornaday, which came about through my initiative.

One afternoon as Charlie and I were returning from several hours of climbing to look at the goat remains on Phillips Peak, the trail led across some slide-rock which gave us an open view upward toward the west. In an evil moment, I saw to the westward a ridge that was heavily timbered quite to its summit; and seeing no land higher up, I rashly concluded it was a low pass. So I said, “Charlie, it doesn’t look far up to the top of that divide. Suppose we climb up, and take a look over the other side, toward Bull River.”

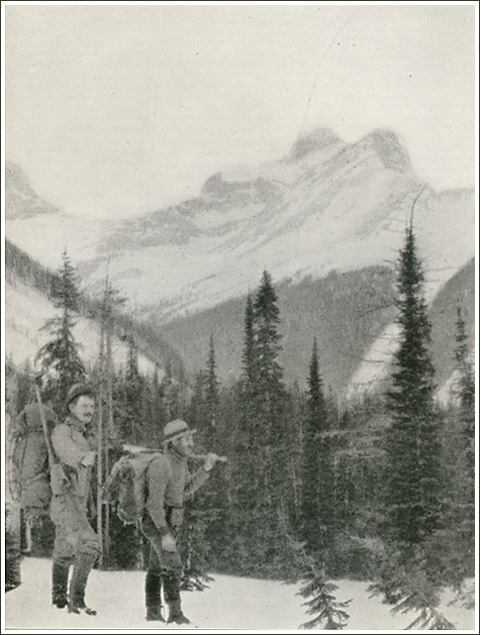

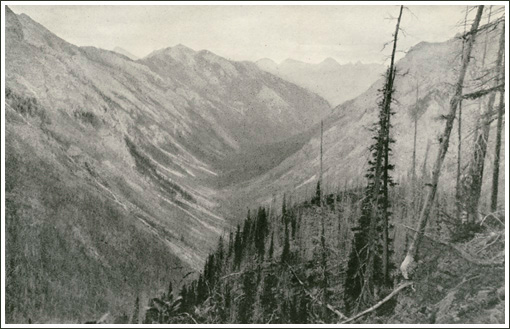

Phillips Peak As Seen From Bird Mountain

Phillips Peak As Seen From Bird Mountain

Charlie hesitated two or three seconds, looked at the sun, then quietly answered,

“All right… We’ll strike up on the right of this slide, and have easy going.”

We struck up, and the climb through the green timber was all right. But when we reached what I had thought was the summit of the divide, behold I we stood at the mouth of a big, bare basin between the two peaks, beyond which there rose a roof of the steepest and most difficult slide-rock that I found on that trip. We were at timber-line, and exactly half-way up to the real summit! I felt as if that notch had deliberately deceived me.

After a brief rest, we crossed the bottom of the basin, chose the best line of ascent, and started up. Never shall I forget that climb. The mountain was frightfully steep, and from basin-bottom to summit, the slope was covered with slide-rock of the best possible size to roll under a climber’s foot, and throw him down.

“Be very careful of your footing here,” said Charlie, very quietly. “Don’t make a misstep. A roll down here might be pretty serious.”

There was no doubt about it. A genuine fall on that treacherous stuff, either backward or sidewise, might easily send a man plunging downward so swiftly that there would be no stopping short of the bottom. The slide-rock was mostly in angular chunks about the size of furnace coal, and almost as hard as flint. It reminded me of the inch-and-a-half broken trap-rock that we use in the Zoological Park in surfacing our roads. Imagine the steepest house-roof you ever saw bestrewn with that stuff, ready to roll at the touch of a foot, and you will know what that slope was like as a place to climb.

In taking a step upward, the foot had to win a firm resting-place on the loose rock before the body’s weight was thrown upon it; for each step had to be a success. The strain on the ankles was really very severe—and on the mind it was equally so. In a party like ours, no one wants to be a spoil-sport, and get hurt, tie up the whole hunt, and possibly be carried out in a package strapped to a horse’s back. Accidents are forbidden luxuries!

I suppose that slope was about six hundred feet long. Charlie kindly offered to carry my rifle for me, and even insisted upon it; but up to that time I had carried my rifle every step of my hunting ways, and I elected to stay with it, up or down.

As we neared the summit, we saw that we were approaching a “knife-edge.” It was not a level knife edge, either, but sloped sharply, and at one place broke down very abruptly for several feet. It was then clear that the narrow sky-line was the edge of a precipice, that there was no such thing as hunting beyond, and it looked as if no one could walk on the knife-edge for more than a hundred yards or so.

Feeling that I had been grossly deceived by that notch, I decided to expend no further energy upon it, unless something more than the summit were to be gained by it. Twenty-five years ago I would have followed Charlie to the last gasp; but as it was, I shamelessly allowed him to climb on up to the top, alone. The mental and physical exertion of placing my feet about six hundred times in that loose stuff, each time so carefully that my foot would hold without the possibility of a slide or a roll, had so completely exhausted both my nerves and my ankles that I had neither patience nor strength for another useless fifty feet. I learned that a man who is reasonably fresh can do climbing that is almost impossible to him when his feet and his nerves are equally exhausted. It is very trying to climb for an hour with a feeling that one false step, one turned ankle or one treacherous rock will lead swiftly to a battered body and broken bones.

Charlie climbed on up with the sang-froid of a mountain goat, and soon stood on the sky-line, looking over. “How wide is it up there?”

“Well, in some places it’s three feet; but in one place it’s nearly twenty.”

“Anything to do on the other side?”

“No; I guess not. No good ground, no game in sight. There’s no use in your coming up here.”

Climbing down seemed quite as dangerous as climbing up. In descending dangerous slopes over loose rock, I always found myself looking forward to a point of altitude low enough that a fall from it would not quite kill a man; then to the point that meant not more than two broken limbs; then to the one-limb point; to battered knees only, and so on to the bottom. With shoe soles less wooden in their stiffness, and with better nails in the bottom, I would have felt very differently in those mountains.

Perhaps I should note here a few facts regarding the best clothing for a mountain-climber. Naturally, a tenderfoot needs to have all conditions in his favor, but it is likely that few succeed in securing a perfect outfit. The shoes should be high, to protect and support the ankles, but the soles should not be too thick, or inflexible. The soles should yield somewhat to the rocks; and they must be well studded with sharp-pointed hobnails, screwed into the leather. In rough work and plenty of it, two pairs of good shoes will last but little more than a month.

The trousers should be knickerbockers of gray mackinaw (wool), and the openings at the knee should be six inches long, with buttons, in order that in severe climbing they can be opened wide. With these, woolen stockings are necessary. Suspenders are absolutely necessary, for the belt must be worn loose. The outer shirt, of gray flannel, should be of medium weight. The neck demands a large silk handkerchief, of some dark, neutral color.

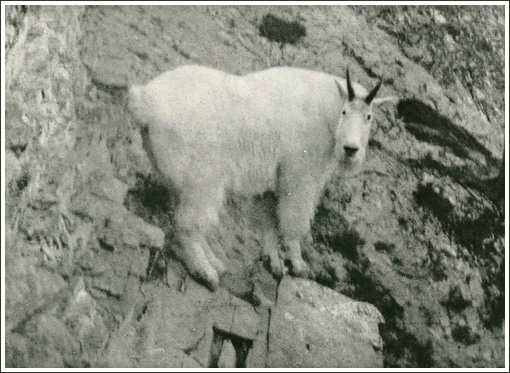

As we climbed down, a solitary billy goat came over the peak in front of us, beyond the basin, and treated us to a wonderful performance. From the side of the peak a thin shoulder ran out toward the Avalanche Valley. It was about three hundred feet high. The “formation “stood on edge, quite perpendicular, and there was a band of shaly stratification which had weathered a trifle below the general surface of the shoulder. I saw a goat appear on the crest of it, and start down what looked like a pathway of smooth and perpendicular rock.

“Charlie, just see what that goat is doing!”

We settled back against the slide-rock, and adjusted our glasses.

“Well!” exclaimed the guide. “He might as well be standing on his head!”

Coolly and deliberately, without any show either of haste or hesitation, that goat walked down the place that looked perpendicular. Not even once did he make a false step, or hesitate.

Over the worst places he came down two feet at a time. He reached down with his forefeet, planted them far apart, then slid his hindfeet down between them until they too secured a good hold. It looked as if his hindquarters rubbed against the cliff; and beyond question, his rear dew-claws and the lowest joints of his hindlegs did so.

Over the lower third of the descent, where the grade was less steep, and the pathway offered rougher footing, the goat calmly walked down to the bottom, crossed the slide-rock and turned off up the basin, toward a patch of grazing-ground. Very soon it passed behind a point that jutted out from our ridge, and for a moment disappeared.

Cautiously we descended a short distance, and again sighted the animal. It was quietly grazing, and not more than one hundred and fifty yards away. We sat down, and watched him until we were tired; and then I decided to test his ears, his eyesight and his courage. Although we were in plain view of him, he paid no attention to us.

I whistled, faintly at first; but he took no notice. I whistled again, loud enough to have startled any deer feeding at the same distance, and sent it flying; but still no notice. Then I gave three or four very shrill blasts, in a manner specially developed in my boyhood. The goat raised his head, and looked about with an air of curiosity, but stirred not from his position, and manifested no alarm. I presume he thought that a whistling marmot had found out how to whistle with two fingers in his mouth.

So long as we remained motionless, the goat was quite indifferent to our presence. When I left off whistling, he went on feeding. At last we rose quietly, and moved on down; and then he decided to be going. I said “Hello,” rather loudly, but he merely went on at a moderately fast walk. When I shouted, he hastened perceptibly; and finally, when I yelled at him, he really took alarm. But even then he did not leap, and stampede in a panicky way, as a deer does. He simply trotted away as fast as he could, climbed the divide before him at its lowest point, and disappeared over its crest.

When Charlie and I reached the bottom of the basin, we examined the goat’s pathway, and, as we expected, found it not so nearly perpendicular as it looked from in front. The angle of it seemed to be about forty-five degrees from perpendicular. The wonder was not that the goat managed to descend in safety over a course on which a man could not have travelled ten feet, but that it came down with such contemptuous indifference and ease.

I am tempted to make note of one other climb that Charlie Smith and I enjoyed together, still in quest of new grounds and grizzly bears. To me the wonders of it, and the weirdness of it, never will be forgotten while I live.

Around the head of Avalanche Creek there was a regular nest of “notches” and “divides,” and “passes” by courtesy so called. We explored each one of them, always climbing, and although we found little killable big game, we were so royally entertained by that grand picture-book of Nature that we felt richly repaid. From first to last I climbed about fifteen mountains in that country, and next to the grandeur of the scenery, its most striking feature was the marvelous diversity of Nature’s handiwork. On no two mountains did we find the vegetation, the ground and the rocks really alike; and this diversification continued to the very last hour of the trip.

Bear with me a moment, and I will set down, as in a catalogue, the salient features of interest that one passes through, or over, in the course of one day’s climb in that Wonderland. I take them all from the notes of the day wherein Charlie and I climbed into the second big notch south of Phillips Peak.

(1) First came the luxuriant, balsamy, sweet-smelling “green timber “of the valley, which climbed half a mile or more up the steep slope. In this the rich earth is smooth, and covered deeply with the dry needles of Canadian white spruce, jack pine, and balsam. The fine-leafed, columnar larches are turning the color of old gold, and the leaves of the quaking asp tell their name by their incessant quivering. Just then the frost was busily painting them Indian red.

(2) Above the heavy green timber comes the dwarf spruces,—which I think must be of a species different from the great tree,—and the patches of yellow-willow brush.

(3) There are patches of hard, bare earth, usually shaly, and often so hard and smooth they are not only uncomfortable, but even dangerous. In freezing weather they must be carefully avoided; for they give no foothold.

(4) The deep gullies that so often score the mountain-sides, cut down through decomposing shale, are a prominent feature, and in traversing the side of a steep mountain in freezing weather they must be crossed with the utmost care. At such times, our guides regard them as decidedly dangerous.

(5) Above the brush-belt, often comes the mossy pasture-grounds, in steps, like great stairs that have been covered with a moss-like carpet of Dryas octopitala three inches thick.

(6) The “slides,” or avalanche tracks, are everywhere present, sometimes bare of trees and bushes, and nicely set in grass, and again thinly covered with young trees.

(7) In places are found large patches of fine, loose earth, perfectly bare.

(8) Slide-rock is always to be expected, sometimes coming from sources that are visible, and again descended from goodness knows where. High up, it is usually more finely broken than lower down. Near the top of a steep divide, or “pass,” it is common to find a wide belt of bad slide-rock (called “scree “by the professional mountain-climbers, and “talus “by geologists), and often the top also is completely capped with it.

(9) Occasionally the climber strikes a stretch of small stones, or, better still, an acre or two of loose shale, which is very safe and comfortable while it lasts. Down a good stretch of this one can plough along fast and fearlessly, as one descends the ashy side of Vesuvius, covering two yards at a stride.

(10) When it comes to snow, and ice,—that is another story, and a long one.

It was through a bewildering succession of such features as the above that Charlie and I made a long and arduous, though nowise dangerous climb, to the top of a pass that looked over into the Elk River water-shed. It was a cold day, and the changes of temperature that a climber experiences in one day were absurdly numerous.

I started up wearing my elk-skin hunting-shirt, a silk muffler around my neck, and two suits of underclothing. At the head of the creek we took our last drink of water, and began to climb upward through the green timber. There being no wind to speak of, the exercise warmed us.

At 500 feet up, my gloves came off, were labeled “not wanted,” and stowed away in the hold.

At 700 feet, off came my silk muffler.

At 1,000 feet, my hunting-shirt was voted a superfluous luxury, taken off, and strapped upon my back.

At 1,500 feet, my shirt-sleeves were turned up as high as they could go.

At 1,800 feet, all my shirts were opened wide at the neck, and we had to wait for more air to blow along.

At 2,000 feet an icy-cold wind struck us hard, and the mercury began to fall. Collars were hurriedly closed, and sleeves unreefed and made snug. To take off one’s cap to mop away perspiration was like thrusting one’s head into a pail of ice-water.

At about 2,300 feet above Avalanche Creek, we reached the summit. It was as cold as Cape Sabine, and the icy wind blew half a gale. The rapid evaporation of the perspiration in my clothing made my body feel like the cylinder of an ice-cream freezer. With all haste, we flung on our outer garments, put on our gloves, and hurried over the sky-line to get out of the wind.

A short distance down the eastern side we found an old goat-bed, in a little depression. In this we crouched, to scan the magnificent landscape below, and if possible to get less cold. The grandeur of what we saw instantly made us forget the icy wind.

The summit behind us was not wider than a city lot, and in one magnificent sweep of half a mile, without a big rock or a tree, it swept down, down, down to the bottom of a huge, green basin in which a grand army could have encamped.

On our right, and close at hand, there rose high above us,—and also dropped far below,—the most awful wall of rock that I saw in British Columbia. From bottom to top its perpendicular face was, I am sure, not less than a thousand feet. From it, there was an almost continuous rattle of falling rock. Even had we seen a sheep on the face of it, we would not have had the heart to shoot the animal and see it fall off.

The impressive height of that grim wall was strongly emphasized by the softer details of the great basin far below. It was fitting that the grandest precipice should rise from the grandest basin in those mountains, and cradle at its foot a tiny lake that was like a big emerald.

The world below us was unrolled like a map. The outlines of the dark-green timber, as yet untouched by fire, and the intervening patches of light yellow-green grass, hemmed in on two sides by frowning walls of dark gray rock and bounded in the distance by a succession of mountains running thirty miles away to the snowy peaks on the Continental Divide, made a grand and impressive picture.

For half an hour we sat with our backs against the mountain-side, absorbing the magnificent panorama into our systems. We spoke little. All at once I saw something new, and looked quickly at Charlie. At the same instant his face lighted up with a gleam of intelligence, and he looked sharply at me.

“An elk, Charlie?”

After a little pause, with his glass at his eyes, he answered,

“Yes; a full-grown bull… That’s the fellow whose trail we found yesterday in False Notch.”

Far down in the bottom of the basin, where the green timber halted at the foot of our slope, an elk had walked out into the middle of a little grass-plat, as if to give us the pleasure of seeing him. He carried a good pair of antlers, and he looked big and beautiful. It was indeed a keen pleasure to see a living, wild, adult bull elk in British Columbia, and to know for fair that even there the species is not yet extinct.

For about five minutes the majestic animal grazed on the grass-plat, then marched to the edge of his little glade, and browsed on some of the green branches that he found there. Finally, like a dissolving view he vanished in the thick green timber, and we saw him no more. It was the only elk that was seen on that trip.

There was no other game visible in the great basin; and we voted unanimously that it was out of the question to descend that long eastward slope, hunt through the basin, and recross the mountain to camp, all in one afternoon.

We decided to hunt back home by skirting the eastern mountain-side of Avalanche Creek, at timber-line, and thereby have a good look for both bear and sheep.

First we went to look at the carcasses of the four goats killed on Phillips Peak, and finding no bear-signs about them, we swung off on our long mountain-side tramp.

By that time, the day had grown stormy. The west wind had borne up a mass of leaden clouds that completely obscured the sun; but fortunately they flew well above us. It was evident that snow was on the wings of the wind. Whenever we crossed a wedge of green timber we went at a swift pace, but at every basin, and every open pathway of an avalanche, we hunted very cautiously.

Before our progress, that mountain-side unrolled like a panorama, in an endless chain of timbered ridges, hollow basins, steep slopes, ridges of slide-rock, and frowning cliffs looming up into the flying clouds.

Once we passed a very curious feature. From the side of a cliff, half way from basin-bottom to summit, there came out a huge mass of slide-rock that looked like an enormous dump from a mountain mine. The level top ran back to the face of the rock wall, and it looked as if cars had run out of the bowels of the mountain, and dumped there ten million tons of broken limestone, in slide-rock sizes. The resemblance was perfect, and I told Charlie to enter the name of that feature as “The Dump.”

That was an awe-inspiring scramble.

Even a sensible dog would have been impressed by the majesty of the rugged rock walls towering heavenward; the rugged terrors of the acres and acres of cruel slide-rock; the weird, squawking cries of the Clark’s crows and Canada jays that circled about us, or perched briefly on the tips of the dead and ragged spruces; the whistling of the cold, raw wind through the pines, and over all the dull gray clouds flying swiftly and silently across the tops of the peaks.

We climbed on and on, seeing much but saying little. In a patch of green timber, we found a nut-pine tree that had been butted and badly scarred, by a mountain sheep ram. Its stem was about ten inches in diameter, and about three feet from the ground the horns of a lusty sheep had battered the bark off, quite down to the wood. Two long, elliptical scars were left, with a narrow strip of living bark between them, as a record of the time when a well-fed ram passed that way, and was seized by the boy-like impulse to carve his name in the bark of a tree. This is a favorite pastime of mountain sheep rams during the months of September and October, when they are so full of grass and energy that the mountains seem scarcely big enough to contain them.

To scramble for several hours along a steep mountainside, going always in the same direction, is very wearing upon the ankles, and tends to make one leg shorter than it really ought to be. At the “psychological moment,”—whatever that may be,—Charlie changed our course, and bore diagonally downward until we struck the bottom of Avalanche Valley close to the circle of light that radiated from the blazing logs of our royal camp-fire.

And then it began to snow.

William T. Hornaday, Sc.D.

Director of the New York Zoological Park

From Boone and Crockett Club’s Classics “Camp-Fires In The Canadian Rockies”

Written November, 1905

The Boone and Crockett Club is pleased to offer a new series of digitally remastered classic hunting and adventure books. Each book was authored by a member of the Boone and Crockett Club in the late 1800s or early 1900s and was hand-selected by a committee of vintage hunting literature experts. Readers will be taken back to a time when hunting trips didn’t happen over a weekend, but were adventures spanning weeks or months. You’ll be pleasantly surprised by the high-quality photographs and drawings from decades long gone that are scattered throughout these titles. This series includes book by renowned adventure authors such as Theodore Roosevelt, William T. Hornaday, Charles Sheldon, and Frederick C. Selous, to mention only a few. Available online at: