Hungarian born Guy Jonas, founder of the taxidermy studio that we took over, Jonas Brothers of Seattle, once stated, “If ever the Soviet Union opens its doors to hunting, it will be the world’s greatest hunting grounds.” Amazingly, less than 20 years later in 1970, I personally was the prime factor in opening the doors for foreign sportsmen to begin collecting specimens from behind the “Iron Curtain.”

Brother Bert’s and my activities in Outer Mongolia in the late ’60s had us traveling through Moscow, which was the only entryway into that country. I spent considerable time in Moscow with the heads of Intourist, the Soviet agency for all travelers, whether for business or pleasure. I even spent time in Alma Ata, Kazakhstan, and the largest of the Asian republics, discussing their wildlife potential. Not only did I meet with Intourist personnel, but also with wildlife officials such as Vladimir Fertikov, head of Glavakhota, the board of wildlife reserves for the Russian federation, and also in Kazakhstan, the Minister of Forestry, Alexander Amanbaev, and the president of the Wildlife Department, Valery Savinov.

The wildlife officials were eager to allow hunting, but they said they could do nothing without a directive from Intourist. My main contact in Moscow was Valery Uvarov, Intourist’s director for all of North America and Latin America. We became very good friends and he was able to negotiate an expedition in and around the Caucasus Mountains in the southwest of the U.S.S.R. (Union of Soviet Socialist Republics). It was for two people: Dr. Arthur Twomey, representing the Carnegie Museum, and myself.

Since all travel in the Soviet Union had to be pre-planned and prepaid, it was not possible to book our trip in the normal fashion, as there were no established tariffs. After several tries, Valery was able to get this information: It would be 5 rubles per day for a huntsman, 5 rubles for a horse, 25 rubles for hut accommodations, 25 rubles for a jeep, etc.

“OK,” I said, “How long, how many huntsmen, horses, jeeps?”

They could not answer, so Valery said I would have to go find out myself. He booked us for six weeks of deluxe hotel accommodations in the nearest cities to the reserves that we were to visit. He told me to take a lot of our travel vouchers (similar to blank checks) along and pay on the spot for services received, then report our accounting back to him when we returned to Moscow.

This process probably never happened before in the U.S.S.R., and I was honored by his trust and cooperation to fulfill my dream hunt. Because of this maiden trip, I established the first written tariffs for hunting in the U.S.S.R., and our agency became the first to book organized hunts as a general agent.

Russians do like to hunt, and a number of reserves had been established in recent times, mainly for the use of the Republics’ hierarchy and certainly not for the common folks. It was in these reserves that Valery was able to get permission for our hunt and for other foreigners to follow. Here is a brief story of this history-making trip.

It was mid-August of 1970 when, after a few days business in Moscow, we arrived in Baku on the shores of the Caspian Sea. This is in the Republic of Azerbaijan, which translates into “Land of Fire,” because of the eternal gas flames early travelers saw coming from the ground. We were met by Rafik Kapharov who was assigned to be our personal guide and interpreter for ventures into the Kubinsk Wildlife Reserve in the eastern end of the Caucasus mountain range.

The Caucasus is a high, rugged mountain range, much like the Cascades of Washington and British Columbia. The snow-clad mountains run northwesterly from Baku for a few hundred miles. The mountains and the surrounding foothills have been known for a wide variety of unusual game.

I do not know what Valery Uvarov had said to the local authorities, but we soon found out that our trip was regarded as very important for the future of a Soviet hunting program. The “Red Carpet” (not a pun) was out for us from the beginning and they responded to our every wish, as if we were the Soviet hierarchy they were accustomed to serving.

It took us two days to reach and establish our base camp. Several jeeps were provided to take us to a village called Derk, where we were provided with horses to ride and pack our outfit into our campsite in a rugged draw as high as possible in the Caucasus, where there was still a flat enough place to pitch our tents.

This rugged area had recently been set aside as the Kubinsk Wildlife Reserve, the habitat of a pseudo sheep called the Dagestan tur. Every day we went out to a different area and each time we saw tur. The mountains were literally covered with these magnificent animals and an obvious need existed for an aggressive hunting program.

Man was their only natural enemy. There were no wolves and the bears here were satisfied with the great amount of vegetation. We did see the Asian mountain grizzly, which is called “brown bear” there, but the fur was quite shaggy and subprime, so we elected not to collect any here, as we were to be in at least two more bear-hunting areas later.

We stalked the tur extensively and worked with the local guides in developing techniques for them to spook the game out of their rugged habitat into areas that are more accessible. By the time we could get up these vertical mountains where the tur had been grazing, they had often settled down into treacherous rocky gorges, where it would be extremely dangerous for us to venture. Therefore, we constructed some rock stands in natural crossing places, such as saddles and trails from these gorges.

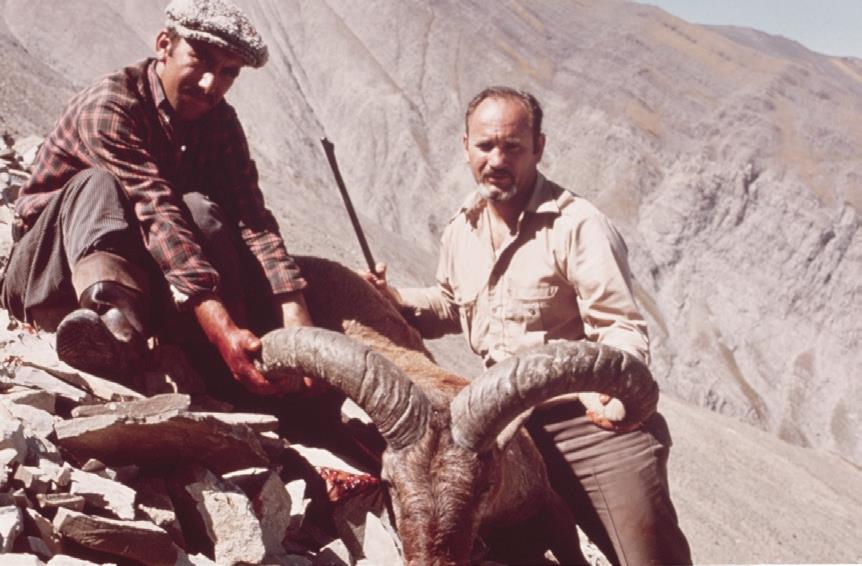

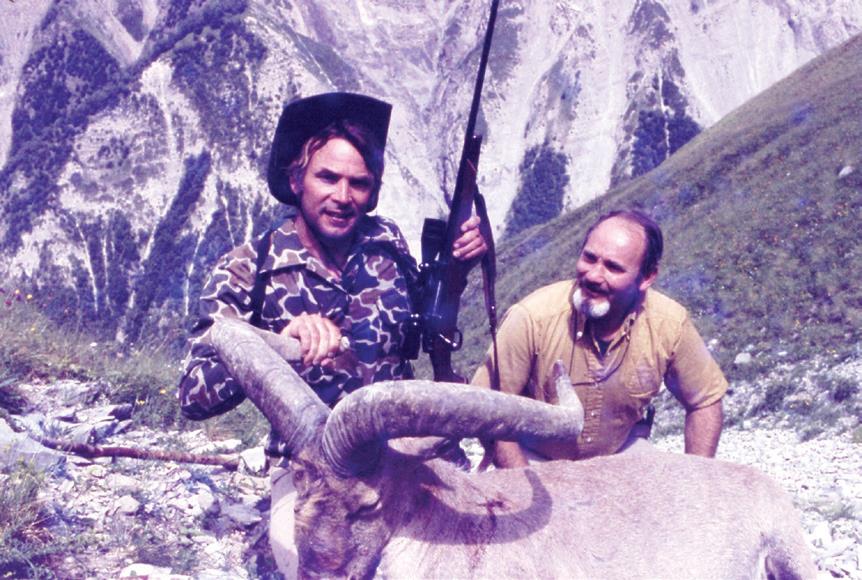

The Soviet guides would then surround the opposite sides of the gorges, exposing themselves, making noises and often firing their shotguns in hope of moving the game in our direction. This method worked quite well and has been developed into a science through the years that followed. Twomey and I collected excellent trophies for the Carnegie Museum and for personal use. The tur is about the size of the Rocky Mountain bighorn sheep and has horns with about the same mass. Even though it is considered a goat with the scientific name Capra cylindricornus, it is much more like a mountain sheep.

We were the only foreigners on a flight from Baku to Mineralney Vody (Mineral Water). From the airport, we were driven about 25 miles to the resort town of Pyatigorsk, where we spent a delightful night. The next day, we were driven several more hours to Ordzhonikidze, a city overlooking the north central Caucasus.

Following a couple of days of discussion, we headed to a newly built deluxe lodge at Saniba inside a game reserve in the Autonomous Republic of North Ossetia. This is a progressive part of the Soviet Union, and they had a newly established game department, members of which were to be our guides and hosts for our stay in the area. In our previous visit in Azerbaijan, there was no game department. Our guides and hosts while in the mountains were from the local hunting society, which at the time was a hunting club assigned to oversee the Kubinsk Reserve. We were escorted to the game department headquarters, which consisted of modern premises with large statues of wildlife in the garden area.

The Saniba Lodge overlooked the meadows and lush foothills, as well as the towering snowy peaks of the central Caucasus. Within the view, we could see the habitats of tur, chamois, maral deer, roe deer, Russian boar, European bison, and brown bear. In the mountains, we had to use our own ingenuity in making a spike camp, since they did not have any tents available. We built a sort of overhang over a cave where seven of us slept in an area not quite big enough for two.

After looking over the tur, we found them to be the same variety that we had seen in Kubinsk. We had hoped to find the west Caucasian or Kuban tur but, since we did not, we elected not to take any more tur specimens.

The areas available for tur hunting are quite expansive compared to Kubinsk in that the starting points were accessible by two good roads that can take hunters relatively near to the hunting areas. We had horses available to take us from road’s end to our spike camp. We saw signs of maral stag in the high valley floors, but we did not take much time to hunt stag, as we were scheduled to do that from the Saniba Lodge.

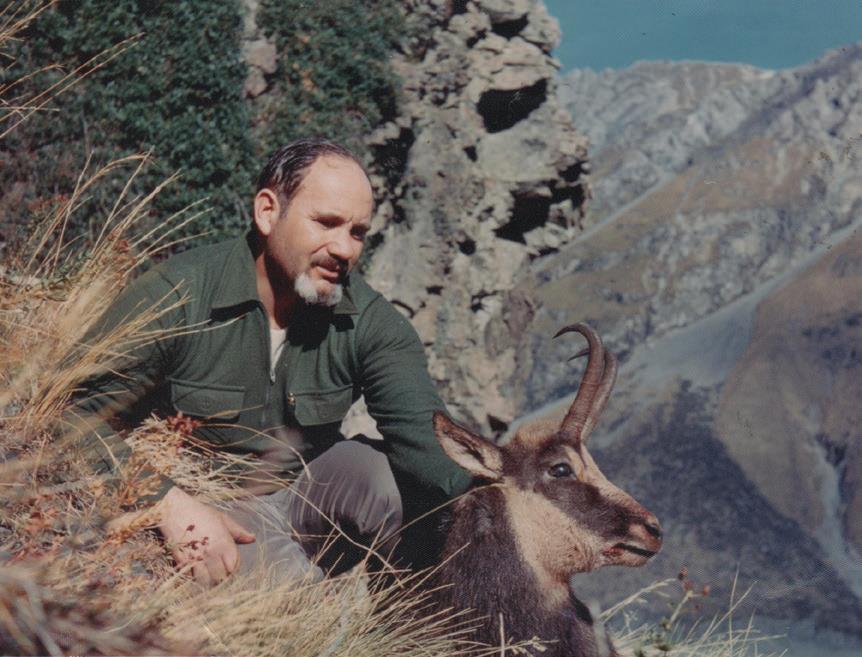

From the lodge we collected brown bear, boar, roe deer, and maral stag. They used every method of hunting conceivable, which included stalking in early morning and late evening and driven hunts during the day. One day they took us to a distant area and had us go out by horseback, a treat that they used for visiting dignitaries. A side trip with a fly camp got us into the chamois area down range.

During our hunt, we had received several messages from the next area to be visited, encouraging us to go there as quickly as possible. Therefore, we rushed things somewhat and left before our hosts were really quite ready for us to leave.

We were driven southward over the Caucasus, through many hairpin turns to the city of Tblisi, the capital of Georgia. Then we were flown to Adler near the resort town of Sochi on the Black Sea, before being driven to the headquarters of the Krasnaya Polyana Reserve in the forested foothills on the west side of the northwest end of the Caucasus.

This reserve is part of a large area, the Krasnodar State Forest Hunting Reserve. The director of the reserve explained that their main trophies were the brown bear and Russian boar. Now in late September, the animals fed mostly on the wild fruits, berries, and nuts that were ripe at this time and the hunting was at its best, the reason for the urgency to start the hunt.

As in the other reserves, we were treated royally at their headquarters for a day or two before being taken to our first camp, which was a newly built cabin in the forest in an area surrounded by wild pear trees and chestnut trees. We practiced the usual stalking and driving of game as well as sitting at night in nut tree groves while waiting to hear the munching of nuts by bears and/or boars. Another “camp” was out of a beekeeper’s farmhouse—our lunch consisted of honeycomb and all the fruit, nuts, and berries we could pick as we ate our way through the day.

Game was abundant, but we did not take a bear since we had already shot bear in the last area. We felt we had taken our share, much to their disappointment. We did take boars, which are extremely impressive trophies as they are large and well furred unlike the so-called “Russian boars” that have been transplanted to many parts of the world and are usually as scraggly looking as a barnyard pig.

The demand for time in these three areas consumed most of our allotted time on our visas, as well as our budget, so we canceled our other planned stop in Krasny Les to the north and part of the Krasnodar State Reserve, which specializes in maral stag and roe deer. Since we had collected those animals in North Ossetia and now had a good feel for the overall situation in the U.S.S.R., we returned to Moscow with our report. As a result of these exploratory trips, I structured the first official “Tariffs and Conditions for Hunting in the U.S.S.R.”

In the years following the grand opening, sportsmen flocked past the Iron Curtain from all western countries. As part of our general agency agreement, we wholesaled the hunts to other agents. However, as time passed, the officials at Intourist gave in to demands of appointed travel agencies to deal direct. European agents asked, “Why should we deal with an American company and have to deal through the American department of Intourist?” So I agreed, but my agency still offered the product to any agency that desired our services.

Editor’s Note:

We’d like to thank Skyhorse Publishing for graciously allowing us to re-publish this excerpt from Chris R. Klineburger’s landmark book Gamemasters of the World: A Chronicle of Sport Hunting and Conservation. If you’re even remotely interested in international travel, culture and hunting this is a book that belongs in your library.