In the past few years the concept of the hunter “athlete” has thankfully begun to replace the media popularized stereotype of the blood lusting, beer swilling redneck shooting deer from the lawn chair in the back of his truck. Marketing and advertising campaigns feature hunters on impossibly steep slopes and lonely ridgelines deep in the backcountry in pursuit of their prey. Photos of hunters with their heads down, faces reveling in the duality of joy and agony only a successful hunter knows have become the de facto “money shots” for gear and apparel advertisements. From films to equipment and apparel, companies are spending and making millions of dollars catering their products to this “new” hunter-athlete niche. Indeed entire companies have formed with the hunter-athlete at its core. Apparel companies like Sitka Gear, Kuiu, Kryptek and First Lite were founded on the very basis of serving this “growing” segment within the hunting industry.

But is this really a new concept? In a remarkably surprising (for being in Outside) and well written article in the March 2013 issue of Outside Magazine the author Grayson Schaffer wrote, “Hunting is making a comeback by tapping into a new crowd of athletic locavores…” highlighting as many do (and should) the organic, truly free-range meat one procures when hunting for your own meat. Yes, in this way hunting is making a comeback but mainly to the leather wearing, packaged meat buying urbanites that were too busy protesting trophy hunting to think critically about the food on their plates and how in the hell it got there. No, the “athletic hunter” is not a new phenomenon, but I welcome the polished and now well marketed image of the athletic, hunter-conservationist that hunts for his or her food in a manner respectful to both the animals and the environment while pushing the limits of physical endurance, strength and mental fortitude.

I would argue we have always been here.

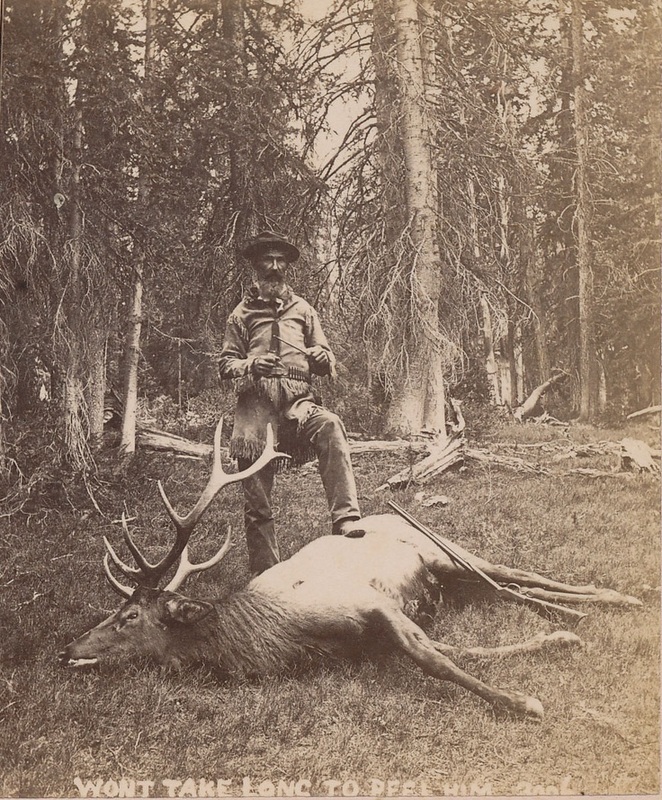

The very formation of many of the National Parks, Game Preserves, and Protected Areas around the world can be traced back decades if not centuries in some countries to hunter led organizations often founded by those at the forefront of wilderness exploration. Men and women that even then, before “technical” apparel and “ultralight” gear were considered integral to success were enduring significant physical hardship in the name of hunting, exploring and discovering the wild places of our Earth. These early “athletes” were going afield for months or even years in the pursuit of fur, game and the exploration of vast unmapped tracts of land.

And yet, can we not trace the origins of the “hunter athlete” even farther back in our history than this? Were hunters in fact not the original athletes of the human species? Is the human body not at its very origin an organism uniquely built to hunt and gather? Anthropological data supports the fact we’ve been hunting, scavenging and foraging for a minimum of 2.6 million years and initially we likely would have scavenged and foraged as much as we hunted. However, we have definitive archeological evidence that shows we were hunting large animals like wildebeest and kudu 1.9 million years ago. This was before we had conceived of weapons like bows or even spears and in a world without cities or any form of organized communities, our nomadic ancestors were constantly moving in search of sustenance at significant caloric expenditure. The average daily distance covered by modern hunter gatherers ranges from 9km to 15km so it’s not a stretch to expect our earliest ancestors covered at least this distance if not more on a daily basis.

In his book The Story of the Human Body, renowned evolutionary biologist Dr. Daniel Lieberman of Harvard University paints a vivid picture of just how athletic we were at the dawn of the Paleolithic age, citing numerous anatomical adaptations that made us uniquely specialized long-distance hunters such as our long limbs, relatively hairless physique and springy, elastic feet and lower-leg tendons. More importantly he posits the theory that it was hunting and our physical abilities to do so that brought us to where we are today on a cognitive level as much as a physical level. He writes:

“Today few people know much about the animals and plants that live around them, but such knowledge used to be vital. Hunter-gatherers eat as many as a hundred different plant species, and their livelihoods depend on knowing in which season particular plants are available, where to find them in a large and complex landscape, and how to process them for consumption. Hunting poses even greater cognitive challenges, especially for weak, slow hominins. Animals hide from predators, and since archaic humans couldn’t overpower their prey, early hunters had to rely on a combination of athleticism, wits, and naturalist know-how. A hunter has to predict how prey species behave in different conditions in order to find them, to get close enough to kill them, and then to track them when wounded. To some extent, hunters use inductive skills to find and follow animals, using clues such as footprints, spoor, and other sights and smells. But tracking an animal requires deductive logic, forming hypotheses about what a pursued animal is likely to do and then interpreting clues to test predictions. The skills used to track an animal may underlie the origins of scientific thinking”.

Yes, in his opinion hunting and the intellectual stimulation and challenges of tracking, pursuing and harvesting game may form the very foundation of scientific and critical thinking, a truly unique human quality. He suggests that this combination of physical ability and cognitive prowess made our ancestors uniquely capable of handling long, grueling pursuits of quarry, under ever-changing circumstances. Our earliest hunts were mostly likely “persistence hunts” where we would track and literally run our prey to exhaustion so we could dispatch the animal with a blow to the head. Even before we possessed the intelligence to make weapons we were hunting.

So why do I cover this in our inaugural Mountain Fitness article? Because, it showcases the very core beliefs of our training concepts and the focus of the content in the months to come. Without a thorough understanding of our philosophy we cannot have a meaningful dialogue. We are not built to simply survive hunting in harsh environments but to thrive in doing so. We are in essence, born to hunt from our brains to our feet. Few organisms that call our planet home are more ideally suited to hunting than humans. From the savannahs to the highest peaks, we have hunted for millennia.

The harsh reality however is the world most of us now live in is a far cry from the natural, physically challenging and demanding world we evolved and once thrived within. Our innately athletic bodies are wasting away at desks, in vehicles and on man-made machines in gyms built to accommodate our ever degrading movement capabilities. We sit at home, we sit in our cars and trucks, we sit at the office and then we go and sit on a “cardio machine” or on some other piece of equipment at some big-box “fitness” facility and think we are preparing ourselves for the hunt. This could not be further from the truth. To be clear, some exercise is better than no exercise and if all you can manage is 30 to 60 minutes at your local “globo gym” on a semi-regular basis then I applaud your efforts. Any preparation is better than none. But if we’re truly going to prepare our bodies to handle the demands of chasing prey in the high, wild and far reaches of the world this is not sufficient. If you intend to hunt in the mountains or wilderness until the day you die this is not sufficient. If you want to avoid overuse injuries this is not sufficient. And if you want the absolute certainty that you will be ready for that hunt of a lifetime, this is not sufficient.

We live in a predominantly linear world now, surrounded by engineered surfaces, structures and equipment. The human body is a three dimensional organism that has been optimized over millions of years to handle an unpredictable and non-linear environment, running, jumping, climbing, lifting, carrying, throwing, all of these tasks require our bodies to handle three dimensional demands. Yes, when you hike into the mountains you go up and then come down but this is a gross oversimplification of the demands placed on the human physique. Side-hilling shale slopes, navigating boulder fields, fording streams and rivers with bowling ball bottoms, crawling and stalking through rocks and vegetation, packing quarters in the dark and even sleeping on an uneven surface all require non-linear strength and endurance. For those of us not lucky enough to spend hundreds of days in the field every year, we must constantly keep these facts in mind as our bodies are slowly but surely being de-conditioned on a daily basis.

Now at this point you may think this is over-complicating matters, that the men and women of years gone by did not approach training in this way. And I could not agree more, in fact I would bet many of them did not “train” at all. But their environment was different and their daily demands were different. If you read your history you’ll know that they walked and rode horses, and worked and lived on their feet more than we do today. But that was a different time. So to counteract the physical effects of living a softer, less physically demanding modern life we must apply the concepts of “natural” or “evolutionary” fitness to our hunting training programs. This goes well beyond wearing your pack to the gym and doing step-ups or working on your squat or bench press. These are all excellent training techniques and have their place in any program but we cannot rely solely on linear movements like these if we intend to excel in our mountain and wilderness endeavours. This is not to suggest we will not cover material at the cutting edge of strength and conditioning science, simply that we must never forget the facts of our evolution and the realities of the world we now live in. The human brain, body and hunting are inextricably linked and have been for millennia and one’s training program should reflect this fact.

In the Mountain Fitness articles to come we will focus on a wide breadth of topics but everything we cover will have this philosophy of the “evolutionary hunter-athlete” at its core. Whether we’re covering injury prevention, nutrition, or techniques for applying evolutionary science and natural training methods to your programming, our goal is to take both your body and your hunting preparation to a whole new level. In reality we’re talking as much about a lifestyle and mindset as we are a physical training concept.

These articles will not only be for those that live in mountainous terrain or communities, in fact our training concepts and topics can and should be applied wherever you live if you ever intend to hunt in the wilderness. More importantly if you want to tap into the full capabilities of your body wherever you live and hunt, this column will have something for you. In our opinion, whether you’re dragging a deer out of the hardwoods or packing a sheep off the talus slopes of the alpine you are an athlete. It’s in your genes. Whatever you hunt and wherever you hunt our training concepts will help you achieve more than you ever thought possible.

I look forward to our ongoing journey together.

Adam Janke

Editor in Chief

Canadian Board Certified Pedorthist

Backcountry Outdoorsman

Ultrarunner

FMS Level 1 & 2