Spring is well on its way down here in the South, and we prepare for the flush of freezer-filler yearlings and blonde bull tahr. For our friends in the Northern Hemisphere, snow is starting to settle and the long winter is beginning. Winter hunting presents a lot of challenges for the serious mountain hunter: short daylight and unpredictable and severe weather are battles we must fight. However, for some the lure of big winter skins and the hope that animals may be pushed to lower elevations is a big draw.

This winter I did a bit of gear experimentation to try and combat what is a real danger and problem for hunters in the winter: ice. Ice comes in all forms and shapes but it always has two things in common: it’s cold and it’s slippery! Modern crampon designs have solved most issues of traveling on frozen snow and glaciers, but there is one type of ice that is a real challenge to walk on: verglas.

Verglas is the term used for a thin layer of ice found on a hard surface, normally rock, and the term literally means “glass ice.” We’ve all experienced the often painful and frustrating experience of walking up frozen creek beds and shingle slides, where often only 1-2mm of ice turns normally easily-navigated rocks into an ankle-twisting, knee-turning nightmare. There are a few options in this situation: go without crampons and try and walk in the gaps; wear crampons and often slip just as much without them (and wear your crampons out on the rock); or try instep crampons or some of the slip-on type traction devices available today.

Or, my preferred option: try something new… but old.

Crampons are a great tool, but on very thin ice on rock they often are not a lot of use and can be just as dangerous as not having them. Also, in mixed terrain the chore of taking them on and off can become frustrating. They are amazing tools that have revolutionized mountain travel, but they are a relatively recent invention and most of the world’s highest peaks were climbed and summited before they existed. Before crampons, it was a world of nailed boots, heavy axes, and generally hard bastards.

offered the user a customization to their boot we cannot

achieve with rubber soles.

There are still guys today that wear hobnails daily for their work, believe it or not, but the rubber-soled boot has all but ended their reign in the mountains. While trying to get my hands on some real boots to nail (another ‘project’ I’m working on) I thought of an idea: Why not test a hybrid boot utilizing both a rubber sole and nails?

I am by no means the first to think of this, and Tricounis have been used for years (I believe the NZ Forest Service made it mandatory for cullers to wear Tricounis for safety reasons.) I have also heard of guys using the odd screw with thick-soled, heavy duty rubber boots. As I researched the options, I came across Kold Kutters. Kold Kutters are an ice screw made purely for rubber applications and used mainly in ice racing on motorized vehicles.

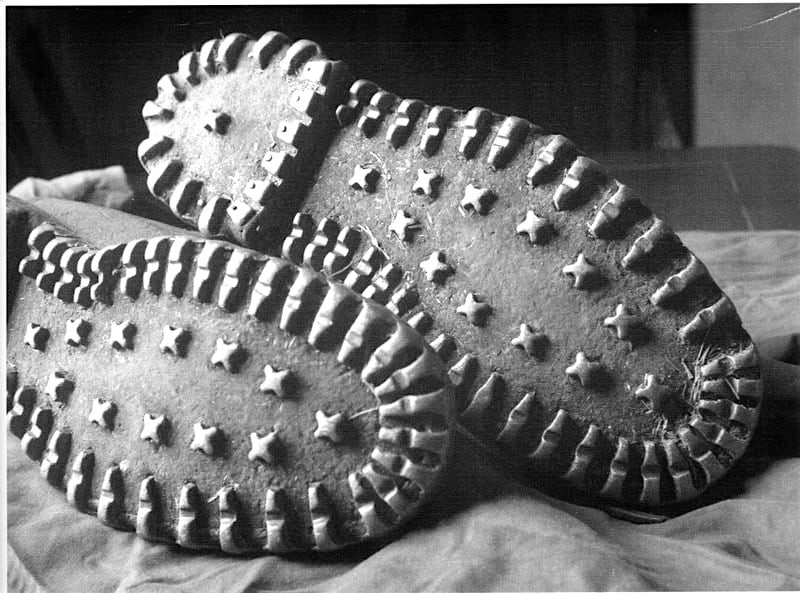

I immediately ordered myself a bag of 3/8” screws. The screws themselves are a hex-type with a fine thread and sharp-edged head. They do come in various lengths, but for obvious reasons I went with the shortest ones I could find. After they sat in the cupboard for a few months, I got my hands on some new Scarpa boots, and with snow on the hills, I set about fitting some of these screws, much to the amusement of my clients. Fitting is pretty simple, just screw ‘em in and away you go. I think adding glue is a good idea, and how many and where you place them is entirely your choice.

In the Field

The first things you will notice with Kold Kutters on your boots is that you are a little bit taller, and that these things really grip! I mean they bite into the ground like nothing else. On pavement and hard surfaces, they’re a little funny to walk on and not the best for the nice carpet in your mum’s living room! But in the hills, they come into their own. My main worry with these was that on dry rock they would be very slick and not grip at all. I was very impressed to find quite the opposite and I found screwed boots to offer far better traction on ALL surfaces tested.

My first test hunt for these boots was ten days of winter tahr and chamois hunting based out of a lower altitude camp due to a varied weather forecast. This meant we left camp every day within the bush line and made our way through bush then scrub then up into the open tops, often in the dark. In other words, I got to test them over a wide variety of terrain types and conditions, from sunny days to heavy rain and snow. The Kold Kutters very quickly gave me a lot of confidence in all the terrain we faced. Those big black slippery logs and tree roots you try to avoid were no issue at all. Frozen creek beds were a breeze, and even on solid dry rock I felt like a real mountain goat; the screws really bit in.

One day I took a bit of a fall — which is quite unusual for me — and quickly found I was losing screws and traction fast! By the end of the hunt the Kold Kutters were all but gone, with only a couple left on each heel. This left me disappointed. The screws worked amazingly well, but if they couldn’t last a week in the hills how practical a solution were they? I did add some basic glue to the screws when I fitted my next set, but I will be trying two-part epoxy in the future to see if that helps. I feel this will also depend on the boot you use and type of rubber in the sole. The boots I used have a soft, grippy sole (Vibram® Total Traction). I would expect that a harder sole is better and suggest researching the sole construction of boots made for the modern forestry industry to see what is used in these applications. Also, I think I could have used a 5/8” screw to get further into the hard base of the boot midsole. Obviously, there is a fine line before the screws become too long, but knowing what I know now I would recommend some careful measuring (or online research) and try and fit the longest possible screw.

I think Kold Kutters do have a place in the mountains; if you can get them to stay in your boots they can offer real advantages in most conditions. They are relativity cheap (in my opinion) and come in packs of 250, so they offer plenty as back up and replacements as they wear out. I think these are worth a look if you find yourself skating around on icy rocks regularly, or even if you are a bush hunter and want some better traction on wet and slippery logs — most forestry boots have some form of spikes for good reason.

Please note that these are NOT a replacement for crampons and are not intended as such. Use common sense in the hills; you and only you are responsible for your safety. If you are going to be in icy conditions, you should have crampons and an axe with you always.

Extra Winter Boot Tips

Keeping your feet warm and dry is essential in the mountains and a lot of users do not have insulated boots, as we often use our boots all year long and for a variety of tasks. Below are a few tips I have learned over the years for slightly increased comfort levels.

Socks are very important and I wear two pairs in winter. I go for as close to 100% wool as I can find and make sure boots are roomy enough for both pairs.

Insoles get talked about a fair bit and I normally run the standard ones the boots come with, or even none at all. This winter I went with full sheep skin insoles and did notice improved warmth.

Snow buildup in the tongue/lace area of the boot can result in heavy, cold, wet feet. A simple piece of foam pad can be cut to fit behind the laces and help prevent this.

Once your boots are wet and cold it can be a real challenge to dry them. Rotating socks and then drying socks in your sleeping bag — or a fire — dries them faster than trying to dry the boots themselves. Another trick is using Nalgene water bottles filled with boiling water as heaters to dry and warm them from the inside. The clear Nalgenes will handle boiling water; the colored ones tend to not handle it so well.

To the North American readers, good luck this winter!

ROAM IS BROUGHT TO YOU BY SCHNEE’S