You cannot control the animals, you cannot control the weather; you can only control your outlook and experience. Surprising as it may be to those who haven’t experienced it, but hunting in the mountains is often as much a mental challenge as it is physical. Here is a classic scenario, and I typically encounter it a couple times a year while guiding in Northern British Columbia around the beginning of September. You wake up one morning to the sound of rain on your tent fly. Steady. Relentless. That’s fine, as you are a dyed-in-the-wool gear nerd and have what you believe to be the best rain gear on the market. Your boots have been freshly treated prior to your hunt — Obenhauf’s is the only correct choice here, I have also used it for lip-chap and weatherproofing my saddle axe — and you can build a cozy glassing shelter with your Sil-Tarp, trekking poles, and para-cord. You lay in your sleeping bag a little longer, preparing yourself mentally for a long day in the drizzling rain, before you finally unzip and take your first glance from under the rain fly. Fog. Dense, heavy, socked-to-the-floor, can’t see sh*t fog.

Those of you who have spent an extended period of time in the mountains know what I am talking about. If you live in a climate that is less than arid — I’m talking to you Alaskans — you have definitely been there. Some of you, in your formative years in the mountains, may have packed your gear and head out for the day. Following your GPS track, or an old horse trail to your desired hunting grounds, only to sit in futility and become increasingly miserable. Best case scenario you see and hear nothing all day. Worst case scenario your presence is met with the sound of falling rocks, and you are left wondering what exactly it was that you just spooked out of the area.

Fog is the bane of the mountain hunters existence. You can hunt in the rain, you can hunt in the snow, but a quick exchange on the topic with any old guide, outfitter, or sheep hunter will inform you that you can’t effectively hunt in the fog. You can’t shoot what you can’t see, and when the mountains are socked in with fog, you can’t see a damned thing.

To be clear, I am not talking about a band of low clouds or fog, moving in and out of the mountain peaks. On days like those, fill your boots. Staying mindful of wind and thermals, a little fog can help cloak your movement, and bring you into a more than comfortable shooting distance on that cagey ram, or the goat bedded in the open with no access. The fog I speak of is the omnipresent sort, from the valley bottom to the highest crags, thick and wet like a drenched wool blanket. The sort of fog that, when it lays unlifted for days on end, will drive most folks to insanity.

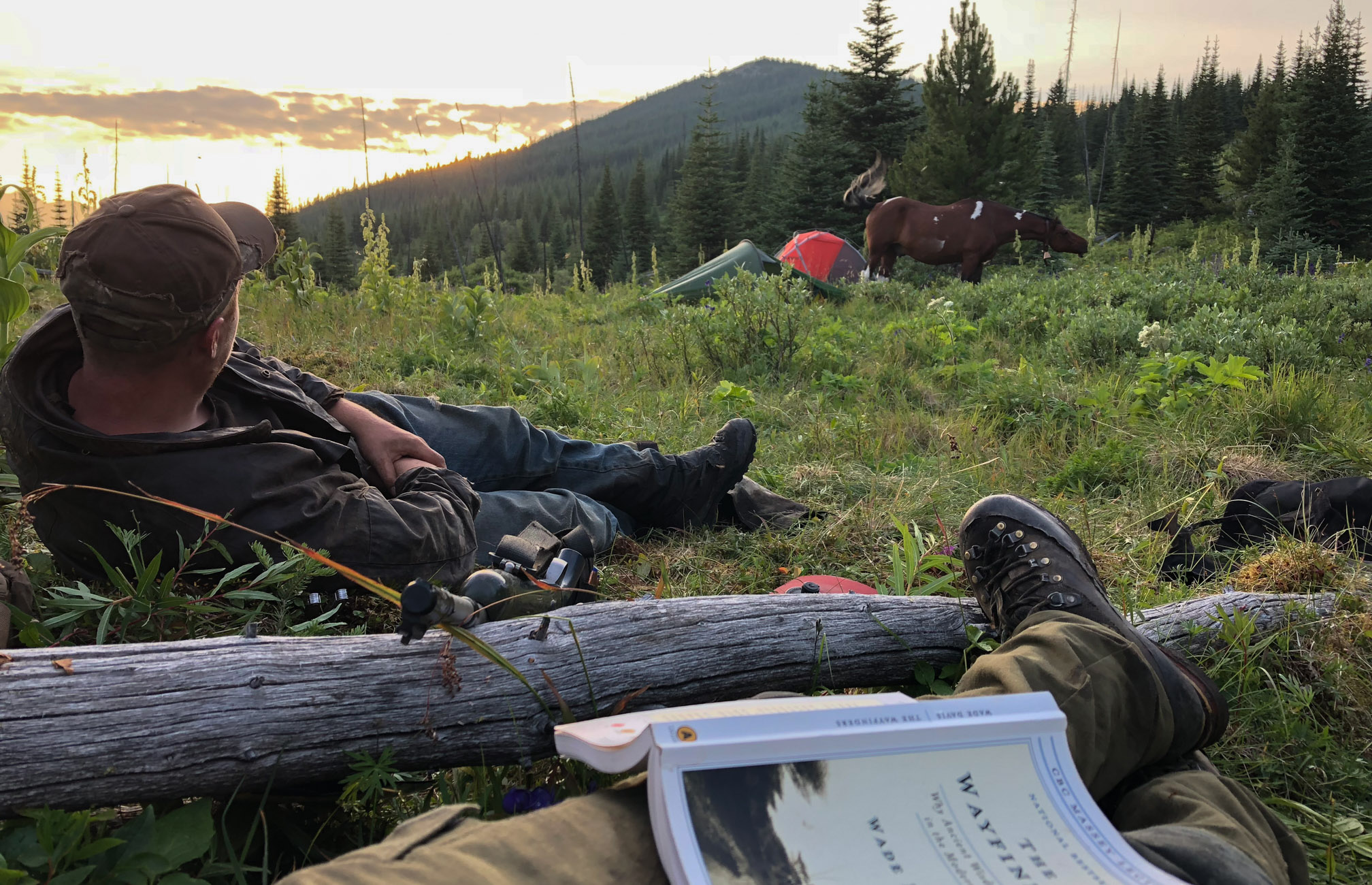

This past season, while waiting for the wildfire smoke to clear from a remote lake, I had the pleasure of chatting with an old outfitter and pilot. Sitting in a decrepit log cabin, aged by sixty-odd years of mountain weather, we sipped coffee and talked about guiding. Of how things had changed over the decades he’d been in the industry. At one point in the conversation, we began to talk about the smoke in the area and the effect it has on game, and coincidentally clients. He recounted a story to me from many years back. He was sitting in his booth at the S.C.I convention, when a man walked into the booth and laid down a series of photographs on the table, photographs of the stone sheep he had killed over the years. Several of the photos featured B&C book rams, a rare and remarkable achievement for a DIY hunter. The pilot recognized one of the rams in the photos, as he had often seen that sheep in his days flying a bush plane around the mountains, and he told the man that he knew where he had hunted that sheep. The man, replying that they had all come out of the same area over the years, asked the outfitter if he wanted to know what his secret was. To be clear, asking a sheep fanatic if they want to know your “secret” to killing old heavy rams is about as redundant a question as humanly possible. The hunter explained that he would stuff his pack full of as many books as he could fit. He would then take a long, slow day climbing into the alpine from the lake he was flown into, set up camp and sit for the better part of fourteen days. Glassing for rams while reading intermittently, he would let his eyes do the walking and burn the books as they were finished.

The outfitter finished his story, explaining that too often we become stressed and rushed, feeling we need to move more to see what we cannot. The reality, he figured, was that we needed to slow down and glass more. When the smoke or fog is thick and low, the best thing to do is read a book.

This is one of the many areas of the mountain hunt that can present a mental challenge. Particularly for clients who have saved up hard-earned dollars, waited several years, and finally set foot in the mountains they have been dreaming of. But patience is an integral part of any successful mountain hunt, as hard as that may be to embody at times. I know the idea of paying fifty thousand dollars for a stone sheep hunt only to be holed up in a tent reading may seem appalling to some, but I can think of worse places on earth to dive into a good novel. In fact, I can think of few places better to read, than in a tent amongst some of the world’s most pristine wilderness. Removed from the external influences of the modern world, you are able to immerse yourself in the author’s writing, and read with a focus that is rarely attainable at home.

For most guided hunts, especially those of the horseback variety, bringing a book or two is certainly a reasonable consideration. Most camps I have been to have a plethora of old books, pages yellowed and furling, sitting in an equally old wooden pack box. A forgotten memorial of days bygone, before clients brought in iPads and smartphones with movies, but rarely are those books of interest, and half of the time they are missing pages when someone needed firestarter. Backpack hunts are considerably more physical, and odds are you won’t have the space to pack around a few extra pounds of books with you — as if I needed another reason to like hunting with horses. Luckily we live in a time of blossoming technology, where nearly everyone carries a smartphone with enough storage to hold a library’s worth of reading, and E-readers are inexpensive, light, and equally capacious.

At this point, you are perhaps wondering why you’ve read several paragraphs for me to simply say “bring books”, which also would make you an unlikely candidate for bringing books into the mountains. I have put together a short list of some of the better novels I have read in the mountains, and not all are related to hunting — though there isn’t a finer place to read an old hunting tale than while hunting. The criteria of my list are rather simple; they are books that I read while in the mountains, and books I thoroughly enjoyed. So without further adieu, here is the official 2018 NMO mountain reading book guide, in no particular order of preference.

A Beast the Color of Winter – Douglas Chadwick

Were there a holy scripture dedicated to those of us who spend our free time navigating the high crags and scree of goat country, this would certainly be it. Chadwick’s writing is obsessively detailed, yet engaging and playful. This one is packed with as much information on goat behavior and characteristics as it is with humorous anecdotes of his time spent in goat country. A mandatory read for any seasoned, or would be mountain goat hunter.

“In North America there is one large animal that belongs almost entirely to the realm of towering rock and unmelting snow. Pressing hard against the upper limit of life’s possibilities, it exists higher and steeper throughout the year than any other big beast on the continent. It is possibly the best and most complete mountaineer that ever existed on any continent. Oreamnos americanus is its scientific name. Its common name is mountain goat.”

Dances with Trout – John Gierach

This collection of essays by Gierach is one of the lighter reads in this list, though that doesn’t mean it should be overlooked. From fly-fishing to hunting, to musings about aging and friendship, Gierach’s work is humorous, and often full of lessons of the philosophical sort. A great read to bolster your spirits on a cold, rainy day in camp.

“If there is an art to it, it’s in the work itself rather than the product.”

Green Hills of Africa – Ernest Hemingway

No hunt camp reading list is complete without a piece from Don Ernesto himself, and while G.H.A never received the critical acclaim of some of his other works, it is still a worthy read. An autobiography of sorts of his 1933 African safari, Hemingway’s love of the chase and the African landscape is wrought throughout. As well, Hemingway makes it abundantly clear that this is a non-fiction piece designed to be read as a fiction, as seen in his Author’s Note:

“Unlike many novels, none of the characters or incidents in this book is imaginary. Any one not finding sufficient love interest is at liberty, while reading it, to insert whatever love interest he or she may have at the time. The writer has attempted to write an absolutely true book to see whether the shape of a country, and the pattern of a month’s action can, if truly presented, compete with a work of the imagination.”

The Dangerous Summer – Ernest Hemingway

Published posthumously, this too never received the acclaim of some of his more well-known pieces, perhaps due to the content of the book, and its unpopularity among American audiences. The Dangerous Summer follows as Hemingway did himself, the series of scheduled mano a mano bullfights in Spain during the summer of 1959, between Luis Miguel Dominguín and Antonio Ordóñez. Despite the technical nature of the language — and my lack of knowledge of bullfighting — his poetic descriptions of the fights, landscape, food, and drink encountered captivate the soul. His love of the art form behind the blood and gore is clearly depicted, and invites the reader to look at the topic in a different light.

”A bullfighter can never see the work of art that he is making. He has no chance to correct it as a painter or a writer has. . . . He can only feel it and hear the crowd’s reaction to it. . . . The public belonged to him now. He looked up at them and let them know, modestly but not humbly, that he knew it. [He] was happy that he owned them.”

Trail to the Interior – R.M Patterson

Patterson paints the picture of an engaging two-part tale in this one. He tells the history of the explorers and fur traders of the Hudson’s Bay, and Russian American Companies on their exploration route from Wrangell, AK, up the Stikine River and Dease rivers and into the Liard and Mackenzie Valleys. In 1948 Patterson decides to follow in their footsteps and takes on the journey solo by means of canoe and steamboat, filling the pages with personal and historical narratives along the way.

“Once man steps into the picture, the very delicate balance of nature is upset. And the wolf has always been the enemy. Too late we may find out that he, too, had a part to play.”

Grizzly Country – Andy Russell

A wonderful blend of stories, compiled over Russell’s many years in the backcountry of British Columbia, first guiding hunters, and later shooting film and video for grizzly documentaries. His observation of the great bear is world class, and his writing light and captivating. Best read while actually in grizzly country.

“Some dogs are born to hunt and some destined to live in sedentary style, never getting far from the comfortable fireside of home. Men are not much different.”

Wilderness of the Upper Yukon – Charles Sheldon

A book that should need no introduction amongst sheep hunters. Sheldon’s account of his 1904-1905 exploration into the heart of the Yukon Territory is a classic, and of particular interest to me as I have guided in some of the areas he speaks of in the book. Like many hunting authors of his time, his stories come from an era foreign to us, where the great mountains and valleys of the North were largely unmolested by human presence, and the hunting took place over months, not days.

“The wilderness was primeval, the sheep practically undisturbed, the other game seldom hunted. It was not possible to find guides, for there were none. It was necessary not only to search out a route to the mountains, but also to find the ranges occupied by sheep.”