My stay at Fort Peck lasted for about a month—from July 29 to August 27, on which day I left by the steamer Key West to go further up the river. This was the first vessel that had passed up stream since I reached here. During the whole time of my stay I had been ill and had been treated with the utmost kindness by Major Mitchell and Dr. Southworth, whose conduct emphasized again the lesson learned long ago, that this world is full of good, kind, high-minded people, no matter what their condition and surroundings in life.

Cow Island Crossing, where we landed four days after leaving Fort Peck, was the only route by which “bull teams” could reach the river. The post was located near the mouth of Cow Island Creek, which comes in from the north, and was the head of low water navigation. By the large freight outfits which came down to the river at this point, was distributed a vast amount of freight over all Montana. The route, after leaving the valley of the river, skirts the foot of the Bear Paw Mountains on the south and goes on to Fort Benton, about a hundred and fifty miles from Cow Island. For protection to the freight discharged here, a company of the Seventh U. S. Infantry was stationed at this point. The freight was under charge of Col. Geo. Clendenin,19 an old-timer in the country and a very intelligent, reliable and good business man. He was from Washington, D.C.

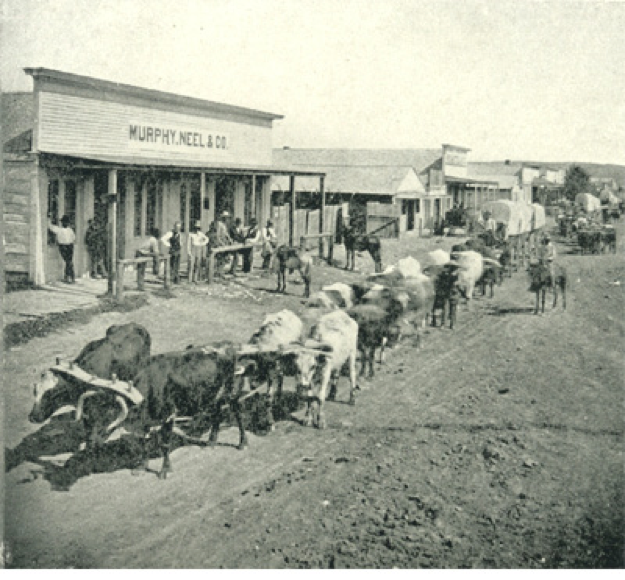

Among the large and well organized freighting outfits of that day, I recall one, the Diamond-R, and another owned by Murphy, Neill & Co. Each outfit consisted of seven teams, and each team of seven yoke of oxen, each team of oxen pulling three wagons linked together. At this time the leading wagon was commonly loaded with about 3,500 pounds of freight, while the intermediate and trail wagons carried smaller loads. To each outfit there was a foreman, a driver for each team and a night herder; all were well armed with repeating rifles. Usually they made camp early in the day and then turned loose their bulls to graze under the control of a night herder until the next morning. The average day’s journey was from ten to fifteen miles. These freight outfits could follow almost any route over the plains country. If they met with steep ravines or boggy places they had the labor and tools to repair the road. In case of a steep, hard pull, the trail wagons were dropped, and each wagon pulled up separately and then assembled at the top of the hill. If danger from hostile Indians threatened, the wagons were brought together to form a fortification, and the nine or ten expert shots within the circle of the wagons usually gave a good account of themselves. It was through men able so to adapt themselves to surrounding conditions that the magnificent Empire of the Northwest was wrested from the control of the savage. At that date Bismarck was the nearest railroad point on the east, while on the south it was Ogden or perhaps Corinne. The great waterway of the Missouri River furnished Montana and a great portion of the British Northwest with most of the necessaries of life, as clothing, sugar, coffee and canned provisions. The only articles of export were gold from the placer mines in the mountains—which usually went out by Ogden—and the skins of various furred animals, such as beaver, fox and wolf, together with the hides of the antelope, deer, elk and buffalo.

At Cow Island I spent a very enjoyable month from August 31 to September 28. Blacktailed—mule—deer were fairly abundant, but there were no elk or bear. I made frequent excursions into the adjacent hills and killed some deer, which were always acceptable at the post. As the weather was dry and the temperature agreeable the time passed very quickly.

During the autumn the gold excitement in the Black Hills brought down from up the river a number of miners on the way to the Hills. From one of these I purchased a black, bald-faced horse, Charlie, with saddle and bridle, while from another I secured a pack mule with a complete outfit for packing. I was now independent, and could go anywhere.

During my stay at Cow Island, two boats came up the river, the Durfee and the Benton. On one of these was Lieut. Schofield, of the Second Cavalry, with a number of recruits.

It was unsafe to make the trip to Benton alone, and for some time I had been awaiting some company, and this was my chance. Lieut. Schofield needed a pack animal, which I had, and which carried a part of our things. A good man was employed as packer and cook, and on the 28th of September we pulled out from Cow Island. On the second evening we camped at the foot of the Bear Paw Mountains. I had gone ahead and killed a buffalo, which furnished food for the fifty souls of the outfit until Fort Benton was reached on the 3d of October.

Fort Benton was then a place of about eight hundred people, and contained three trading stores— I.G. Baker & Co., T.C. Power & Co., and Murphy, Neill & Co. Here I met W.G. Conrad, manager of I.G. Baker & Co., and his brother Charles, who were from Virginia, and had served as Confederate soldiers during the Civil War. I met also Colonel Donelly, who had served in the Federal Army, and who later was conspicuous in the Fenian troubles on the Canadian border. For ten days I hunted with Colonel Donelly in the foothills of the Highwood Mountains, and later made an arrangement with two sons of Mr. Hackshaw, living on Highwood Creek, to make a hunt lasting for a month. Their object was to get a supply of winter’s meat for Mr. Hackshaw, while I was anxious for sport.

We left the Hackshaw ranch October 20 for the Judith Basin, about fifty miles to the south, where buffalo were reported abundant. My hunting companions were Cornelius, twenty-one years of age, and John, sixteen, both wide awake boys and good shots. I took with me my riding horse and pack mule, and my rifle was a long-range Sharp, carrying a 90-450 or a 90-520 shell. Our route lay by the ranch of Oscar Olinger on Belt Creek, and we consulted with him and his partner, Buck Barker, as to the best hunting grounds. They had just returned from a buffalo hunt in the Judith Basin, and told us that a party of Nez Perces Indians of ninety warriors had just passed through the Judith Gap after buffalo. They advised us to go up on the west slope of the Highwood Mountains for elk and buffalo. We took their advice, and on the 29th day of October moved up one of the branches of Belt Creek, a day’s journey, and made permanent camp.

It was on a beautiful mountain stream full of trout, and we caught enough for one or two meals that evening. The next day, riding up to the base of the mountains, about a mile distant, we saw during the day twenty-five deer. I killed a blacktail buck, and Cornelius a whitetail buck. About one o’clock, just as I had killed my deer, a fierce snowstorm set in. When I reached camp with the deer I found everything comfortable. The storm ceased before dark, and during the night the sky cleared.

The next day it again began to snow and stormed hard all day from the northwest, but on the first of November the storm ceased, leaving fifteen inches of snow on the ground. The following day it was cold, only a little above zero, but I hunted and killed nothing. The snow was now getting so deep that the horses could not dig through it and secure food enough to keep them in good condition, so we determined that they should be sent back to the ranch, to be brought out here again as soon as the snow melted enough to enable us to get the wagon out. Accordingly, on the 5th of November, John started for the ranch, packing two deer on one horse and riding the other. He believed that twelve or fifteen miles would take him home, but I feared that he might have trouble with snowdrifts. Cornelius and I remained in camp with little to do, for the snow was two feet deep, and it was difficult to move about in it. However, we had plenty of provisions, abundant venison and a brook full of trout, almost in front of the tent door.

On the 6th of November Cornelius and I determined to make a hunt. We did so, and killed two deer; but returned at night almost broken down with fatigue, for the labor of walking through two feet of snow was extraordinary. The next few days we spent in camp, loading cartridges, fishing and performing various camp tasks. The weather was mild and the snow thawed so rapidly that we determined to hunt the following day. It was still warm, and I set out and followed three whitetails up into the vines where I killed a large buck at three hundred yards distance. On my way home I killed a large doe at a hundred and fifty yards. I saw two elk tracks. Cornelius, who had returned before me, had killed an old doe and had crossed the trail of a large band of elk—forty or fifty, he thought—that had passed through our hunting grounds the day before. One of the deer that he had killed before had been eaten by some large animal.

November 10 was mild again, and the snow too noisy for hunting. I found deer very scarce, and believed that they must have left. I saw but one and got that at long range. On my return to camp I found John had come back with the horses. On his way home on the 4th he was lost in a snowstorm and lay out all night.

Now that we had the horses, we packed into camp the game that we had killed, and Cornelius killed another large buck. On the following day the work of bringing in the game continued. I went hunting in the morning, but saw only four deer, and reached camp on my return just before one of the fiercest snowstorms I ever experienced. The wind blew fiercely, and the snow fell fast, while the thermometer went down to 5 degrees below zero at 7 P.M. The next day it was still colder, 16 degrees below, but windless. We packed up and moved camp to Willow Creek, where there was very little wood. At 6 o’clock the thermometer was 5 degrees below zero. We slept on the snow without putting up a tent, and went to bed early to save firewood. The next day it was warmer, 20 degrees above zero at sunrise, and there was every sign of a hard storm. We determined to go to Highwood Creek without delay and reached Mr. Hackshaw’s ranch by dark. A few miles from the base of the mountains the snow was almost all gone, except what had fallen a few days since. It was reported from Benton that Tilden had been elected President, which greatly rejoiced me.

After a few days at the ranch, I asked Mr. Hackshaw to take me to Fort Benton, and we set out on the 8th of November. In the town I found the result of the recent election still in doubt, and the Democrats very much wrought up over the belief that the opposition was determined to hold the control of the Government at any cost. So strong was the feeling that Colonel Donelly wrote to a prominent Civil War comrade, now residing in Illinois, that Montana was prepared to furnish a regiment of men to assist in seating Tilden.

At that time Fort Benton was remarkable as being the most orderly place in the Territory, perhaps in any State or Territory. There were twenty saloons in the place, yet I never knew a town more free from disorders of any kind. In past years, when two or three “bull outfits” happened to meet there, the men connected with them, having been out on the plains for several months, would often set out to have a good time, and would be very boisterous in the work of “painting the town red.” This had been carried to a point where it became an unbearable nuisance, and at a recent election the best people, saloon-keepers and all, had wished to elect a set of county officers who should reform things. They had chosen a sheriff,20 John J. Healy, a man noted for high character and fearlessness, a county police judge, who was a discharged U. S. soldier of proper characteristics, and other officers of like stamp, and a strong public sentiment sustained all these. At the least disorder the offender was brought before the police judge, who promptly fined him fifty dollars or imposed a jail sentence, or both. This course was firmly carried out until the little jail was full to overflowing, and by that time the disorderly class recognized that the public were determined to have good order, and accepted the situation.

After two weeks pleasantly spent at Fort Benton, I started on December 3 by wagon for the ranch of Oscar Olinger on Belt Creek, about thirty miles to the south of Fort Benton. Here I remained until February 7, 1877. Deer were abundant in the foothills of the Highwood Mountains and Belt Creek valley. The weather was bracing and splendid. For most of the time it was a comfort and pleasure to be all day out of doors, especially when one had an object in view—the finding of meat for eight healthy souls and two dogs. With this feeling and with my love for hunting, it may be understood that these sixty six days were greatly enjoyed. During thirty seven days of this time the temperature in the middle of the day was so mild that the snow melted, and sometimes this melting continued through the night. On only two days was there rain. The temperature was above zero for forty-five days, and at least fifty days were sunshiny. The minimum temperatures for January were 16 degrees below zero on the 23d, and 26 degrees below zero on the 24th. In February the minimum temperature was 15 degrees below zero on the 18th.

The waters of Belt Creek were open over the rapids most of the winter, and on the 5th of February, Donelly and I went fishing near the ranch, and after fishing two hours on this warm day he had caught twenty-four mountain trout and I had caught twenty three; my twenty three weighing, after being dressed, sixteen pounds. I sent these to Fort Benton with my friend Donelly. I did most of the hunting for the ranch, though Olinger occasionally went with me to help pack in the game.

During my stay here I exchanged my horse Charlie for Olinger’s mare Kate, a little animal only fourteen hands high, well-formed and enduring, and trained through Olinger’s long use of her in hunting as a most perfect hunting animal. I valued her very highly and owned and cared for her during the remainder of her life. At this date she was six years of age, and she died at my ranch on the Grey Bull River in 1893, which made her twenty-one years of age at death. Olinger had a well-trained dog, Major, thoroughly broken to follow at heel, and if a deer was wounded he always caught and held it.

At this time and earlier, the plains bordering the Missouri and Yellowstone rivers, the Marias River, the Judith Basin and Musselshell country and the Yellowstone Valley on the south were roamed over by antelope and buffalo in countless numbers. In the foothills of the mountains which rose from the plains were large bands of elk and white and blacktail deer in great abundance. Many of the early settlers of that day, as a means of livelihood, devoted their time to obtaining the hides of all these animals and poisoning the carcasses with strychnine to secure the hides of the large gray wolf, the coyote and other carnivorous animals.21 These hides, after being dried, were salable at the various trading stores. One man, Barker, had a record of killing thirty-two antelope in one day. As the antelope left the. Missouri River, after watering, they went up a narrow coulee in the Bad Lands, from which there was no outlet. Barker followed them, and by his repeating rifle, as they attempted to pass him, he killed thirty-two.

At this time Olinger had a few cattle and had settled down on his ranch to attend to them, while Barker was prospecting for precious metals at the head of Belt Creek. In the end, as the discoverer of the Barker Mine, which I was glad to learn he sold for from $15,000 to $20,000, he was successful. Col. Geo. Clendenin, already spoken of, became in after years manager of these mines, and eventually lost his life there.

Although I was kept fairly busy in securing meat and packing in the deer, occasionally assisted by Olinger, I visited Fort Benton during the Christmas week, leaving the ranch on the 24th of December. When we reached the river opposite the town, we found to our dismay that the ice was running so thick that it was impossible to operate the ferry boat, and we could not get across. We were without blankets, food or firewood; the temperature stood at 12 degrees below zero. There was no house behind us for twenty miles, and before us ran the turbid river, surging with broken ice. We were at a loss what to do. At last someone suggested that three miles below there was a cabin where we might find shelter. We went there, found the owner at home, and he took us in and made us as comfortable as possible. The next morning we found the ice not running and the river frozen over, and by careful sounding with an ax and pole, and stepping from one ice cake to another, we finally crossed over and reached Benton at noon.

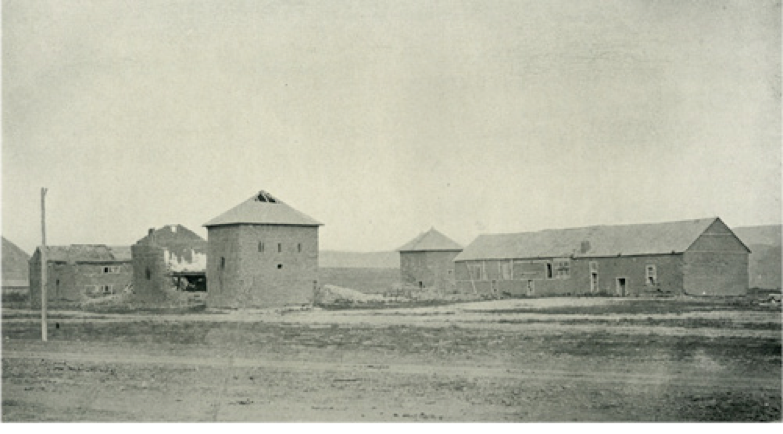

As I walked about the town with a friend, I saw on its outskirts a very large adobe building22 with a high adobe wall in front, and asking about it, I was told that fifty years before it had been built as a fort and trading store by the Northwestern Fur Company; that it had only one entrance through the outer wall, and was built for defense against Indians.

I asked my friend why it was that it was no longer occupied, and he replied, “It is occupied,” and gave me the following explanation:

“When a military post was established at this point, this old adobe building, apparently unoccupied, appeared just what was needed for a fort, and the Government at once purchased it and installed its garrison—two companies of infantry. No sooner were the soldiers settled in their new quarters than the inhabitants, who had occupied these quarters for twenty five thirty years, sallied forth in defense of their home, and in bands of thousands assaulted this detachment of the United States Army. The severe conflict lasted for a week or more. Every device of the military art was brought to bear, every pound of the druggist’s art was applied. All efforts were futile. After a gallant fight this detachment of the U. S. Army was driven bleeding from the fort and compelled to take refuge in a frame building in the center of the town, where it was quartered at the time of my Christmas visit.”

Early in February the blacktail and whitetail deer were both becoming poor, and as winter was now at its worst, I determined to go to Helena, Mont., for the rest of the winter and spring. The contrast between life on a ranch engaged in hard work, and living in town seemed worth trying, and accordingly I started. After spending a week in town I went with I. Hill, the manager of one of the stores, to Fort Shaw, in his buckboard, and from there to Helena, which I reached February 17. Here I spent the remainder of the winter.

My chief recreation in Helena was long-range target shooting with a few gentlemen of that city interested in this sport.

Wm. D. Pickett.

www.historyofhunting.com/acorn-series-ebooks

www.boone-crockett.org