When I returned from fish guiding at Kitchener Lake to base camp at Cold Fish at the beginning of August, I found a film crew set up on an embankment near the horse corrals. Tommy was riding back and forth in front of the cameras muttering the words, “Marion and I left Bella Coola…” while film director Michael Sadlier shouted, “Cut! Cut! Do it again!” for what seemed like hours. Alex Jack and his crew, perched atop the corral rails, watched with great amusement as the scene unfolded over and over again. In fact, so often did Tommy have to repeat his lines that day, they became mantra-like and were repeated by the crew every time a pack train left camp that summer. “Marion and I left Bella Coola….”

Sadlier had been contracted by CBC Television to produce a one-hour special on Tommy’s operation for national distribution. I was never clear why Canada’s national TV network was showing such interest but guessed my father might have called in some favours in an attempt to bring attention to Tommy’s efforts to have a wildlife research station located in the Cold Fish Lake area. I was also never clear about why Tommy wanted the station in his hunting territory but suspected he had ideas about renting accommodation to the researchers.

The film crew and all its equipment had been boated upriver from the ferry crossing on the Stikine to the Spatsizi River, then up the Spatsizi to Hyland Post by Jim Morgan, a slightly-built, recently retired forest ranger in his 60s. Using the 100-horse jet boats of today the trip would have been considered routine. But Morgan, against all odds, did it in a 30-foot wooden boat with a 25-horsepower propeller engine. The film crew then flew to Cold Fish Lake.

As Tommy wished to highlight the fishery as well as the wildlife resources of the area, he had persuaded Roderick Haig-Brown, the renowned author and fly-fishing guru, to come north for the filming. I was allowed to accompany him, a special treat for me as I was in awe of his angling knowledge and his writing for both adults and children. When the filming was over we sat for an hour on the bank of Mink Creek, which drains Cold Fish Lake, discussing the ethics of fishing and hunting, the future of wild lands, and the lifestyle I was choosing.

It was a short while after my conversation with Haig-Brown that most of the film crew returned to Toronto. The footage of base camp and fishing was in the can. Animal shots and sequences from the trail were next on the agenda but, unfortunately, we were short on crew members because of the diet-related exodus of most of last year’s employees. There were not enough working bodies to accommodate extra guests on trips booked for the first part of the hunting season. We decided a cameraman could come back later in the season to get the necessary shots.

In the interim, I headed into the bush with a group of posh customers who were being treated to a hunt by the Boeing Aircraft Company. My hunter, a vice-president of Lufthansa Airlines who had just ordered a fleet of 737s from Boeing, was to spend the next two weeks hunting sheep, moose, and caribou. The length of the hunt was unusual in that Tommy had always refused sheep hunts of less than 21 days. Hunting for a trophy ram – one that is at least nine years old – takes time, unless you are extremely lucky. Hunters, no matter the sought-after species, should set a goal and stick to it. It should not be a matter of shooting the first legal animal that presents itself. I didn’t fully understand the sudden shift in company policy concerning the length of hunts but suspected an emphasis on growth and revenue was displacing the more conservative management of previous years.

We spent the first day on the plateau behind Cold Fish base camp and soon came upon a reasonable caribou bull which my hunter shot. I took the cape and some of the meat but, as we didn’t have a packhorse, I left everything else to be picked up next day. We then started hunting our way home and encountered a couple of bull moose just off the trail. The open flats of grass and scrub birch afforded clear sight lines. The hunter took one of the bulls and, as before, I left parts of the carcass. In those days we were not required to take all of the meat. I had some problems with the apparent waste, but I knew that predators, both large and small, would benefit in the face of approaching winter.

We spent the first day on the plateau behind Cold Fish base camp and soon came upon a reasonable caribou bull which my hunter shot. I took the cape and some of the meat but, as we didn’t have a packhorse, I left everything else to be picked up next day. We then started hunting our way home and encountered a couple of bull moose just off the trail. The open flats of grass and scrub birch afforded clear sight lines. The hunter took one of the bulls and, as before, I left parts of the carcass. In those days we were not required to take all of the meat. I had some problems with the apparent waste, but I knew that predators, both large and small, would benefit in the face of approaching winter.

For sheep we headed to Bates Camp, about a half-day’s ride from Cold Fish. Hunting a ram, as I have said, takes time as the big ones are most often found in high basins remote from human activity. Given the time allotted for this particular hunt, I was growing pessimistic about its success. We had seen several animals but nothing that could be classed as a trophy. As our time dwindled, a Boeing representative took me aside and made it clear he expected a kill no matter what the trophy size. I was taken aback, unsure where my responsibilities lay. At the time there was no size limit on the ram’s head. If it was male it was legal. Could I stop the hunter from shooting what I considered a sub-standard ram, even if it was legal? I decided I couldn’t but found no absolution in that realization. As the hunt proceeded we encountered more small rams that we left. The Boeing representative finally insisted we shoot one that was slightly over a three quarter curl. I was able to rationalize the kill somewhat with the knowledge the meat would be tender and my insistence that every morsel be taken back to camp.

At 20 I was a member of the Disney generation, characterized by people who believed nature was benign and animals imbued with all of the admirable characteristics of humans. Most of my friends had no idea why I found guiding so appealing nor why I would participate in the killing of an animal, especially where the object was to put a severed head on the wall. It’s a question I still grapple with. Certainly hunting has been part of our culture for thousands of years and just as certainly, man is a predator. The act of hunting is extremely satisfying to me. Restricting it to the older and most vigorous animals and thereby magnifying the challenge increases the satisfaction. I do, however, distinguish between the hunt and the kill, the latter often being anticlimactic for me. And two aspects of hunting are absolutely clear in my mind. First, it is a privilege to trophy hunt, not a right. And second, there is an onus on the hunter to act in the interest of the eco-system when exercising this privilege. The same maxims pertain to fishing and fishermen.

We returned to Cold Fish Lake after this hunt, planning a return to Bates Camp next day with a hunter and CBC cameraman Stan Lapinski who had been hired to finish filming the Sadlier documentary. Since the camp would only be unattended for one day, we left it standing and returned to Cold Fish to meet Lapinski’s plane. It snowed the next morning, which delayed the plane by 24 hours – not a long delay but long enough for a grizzly to devastate our camp. We arrived after a miserable trip through wet snow and rain to find food, dishes, and bits of canvas scattered everywhere.

Next morning a brilliant sunrise foretold a better day. Across the valley, on the flank of Nation Peak, sheep pawed the sparkling snow looking for food. As the photographer and I rode out of camp I spotted a large bull moose lying in the sun about a third of the way up the opposite slope. We decided to see if we could get close enough for some footage.

Camera hunting was a new experience for me. Not only did we have to approach undetected to within camera range but the light had to be right and the sun at our backs. We were able to get within 50 yards of the slumbering moose but Stan, who had spent most of his career in a Toronto studio, still had to set up the tripod, level it, then get the moose into focus. Incredibly, the animal continued to snooze through our preparations and into the preliminary filming. We had just managed, I thought proudly, to photograph a big bull at the height of the rut in incredible light. But Stan, the studio artiste, was not happy. The moose was not moving and Stan, cold and impatient by now, wanted action shots. I grunted a moose call. No reaction. I grunted louder and still no reaction. Stan then suggested I go in close and kick the bull’s hindquarter. “Not a good idea Stan,” I said. “This is not a zoo and a bull moose at this particular time of the year might misconstrue the intent.” The moose never did cooperate, at least not to Stan’s satisfaction, but later we were able to get some sheep footage which did have movement, and some frames of our newly reconstructed hunting camp.

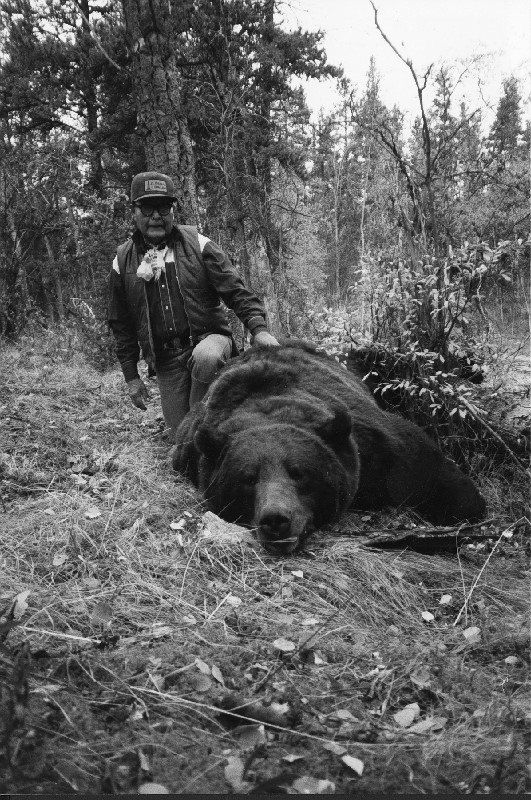

Once the hunter who had arrived with Lapinski had his sheep, we decided to return to base camp. The hunter wanted to work the plateau above Cold Fish for moose and caribou and none of the crew was particularly keen on hanging around for a return visit from the grizzly. The hunter and his guide left first, intending to hunt their way back to the base camp. The rest of us followed with the horses. When we reached the south end of Danihue Pass we spotted the hunters and then heard two shots. When we caught up they were starting to skin a grizzly, providing more excellent footage for the CBC documentary. Since we now had shots of a camp that had been tossed by a bear, and pictures of a dead bear, it was no surprise Stan should want shots of the fully functional version of Ursus horribilis. Easier said than done. Despite our experience of the previous days, grizzlies are not overly abundant in the area. However, after some discussion, Stan and I decided to check the kills made on the plateau a couple of weeks before just in case a grizzly was cleaning them up. The next morning we saddled up and started our long journey to the head of Black Fox Creek. As we were leaving camp, Ron Fleming, a new wrangler still in his mid-teens, quipped, “You aren’t back by dark, we won’t worry ‘cause we’ll know the bear already got you.” For some reason that stuck in my head. I touched my rifle and remained on bear alert all day.

Wet snow in the willows on both sides of the trail soaked our legs as we climbed but there was warmth in the sun, the scrub birch glowed orange under the clear fall sky, and small groups of caribou grazed across the flats ahead of us. There was perfect light for filming caribou and we spent much of the afternoon doing that before moving on to the site where I had left the moose carcass two weeks before. Looking down into the hollow where the kill had been made, we could detect no movement. Ordinarily, you’d see a raven, an eagle, or a whiskey jack working the carcass but there was nothing. We couldn’t afford to just observe for very long because it was getting late. I was puzzled, however, that I couldn’t see any sign of the kill. It had been plainly visible from the same spot two weeks previously. I told Stan to get his camera ready while I went down for a better look. Perhaps because of the warning I had received that morning, I took my rifle with me and chambered a round.

Definitely a studio photographer.