In the late winter of 1908, Chew and I decided on a shooting trip in the following summer to the Thian Shan Mountains, in Chinese Turkestan, where we knew there were many ibex—carrying the largest horns to be found anywhere—with a chance for sheep and wapiti; the sheep being the far-famed Ovis poli. The State Department had our passports vised for us at Pekin—thus giving us the necessary permission to travel in Mongolia—and sent to our Embassy in London, while our Ambassador at St. Petersburg got for us permits to import rifles and cartridges into Russia, together with permission to travel in Russian Turkestan.

In London we tried to get some visiting cards with our names in Chinese on them, but were unable to do so. These cards are of thin paper, 3 1/2 x 7 1/2 inches, white on one side, red on the other, with the name written on the red side in black ink.

It is important that the name on the card should be exactly like the name on the passport. These cards are left at every opportunity.

At the Army and Navy stores in London we bought our camp beds, folding candle-lamps, two large tents, two small shelter tents for servants and to use when away from the main camp, a folding table, a couple of camp chairs of the Roorkee pattern, and two hot water plates, which later we found most useful when the weather was cold.

We also bought three thermos bottles and a couple of haversacks to carry lunch in. My battery consisted of a double 360 rifle by Fraser of Edinburgh, with a single rifle of the same caliber in case of accident, and a shotgun. I had a pair of field glasses and a large telescope by Steward, of London. The glasses were used in finding game, the telescope in examining more closely the game when found, and also in watching ibex when a stalk was impossible. If I were going again, I should take an extra pair of glasses in case of accident, and for the men, who soon learned to use them. A couple of pairs of good shooting boots with plenty of nails and with iron heel-pieces with spikes, completed our outfit, while for clothes we had Norfolk jackets and knickerbockers of a neutral color.

When in London I tried to get an interpreter who could speak English and Russian, but without success, and it was not until we reached Moscow that we engaged a man who had good recommendations, but who was absolutely incompetent, besides being a liar and a thief. This is a most difficult as well as the most important position to fill, as few Englishmen speak Russian and fewer still Turki, the language of the country. I think, however, that anyone taking this trip would do well to give up the idea of engaging a man who could act both as interpreter and caravanbash or caravan leader, contenting himself with an active young man who could speak Russian and English. Such a man could be gotten through any of the American firms doing business in Russia.

From Moscow the train runs daily to Tashkent, making the trip in a leisurely manner in five days, while once a week a wagon lit is put on. The first-class cars are very comfortable. Tashkent, which means “stone camp,” is quite a large town, having a population of 170,000, and is divided into the old or native city and the new or Russian city. The hotel is good, though expensive, and there are good shops, where we bought some cocoa as well as other supplies, which we could just as well have gotten further on and so have saved much time and trouble.

We bought a tarantas for ourselves, as well as a baggage wagon for our outfit and men, for we engaged here as servant and cook a man who could speak Russian and Kirghiz, and who proved most excellent. A tarantas has a body built on poles stretched between the front and back axles, without springs of any kind, except such as are furnished by the yielding of the poles, which is not much, and has a hood like a mail phaeton, with a place at the back for a trunk, as well as a seat for the driver. It is drawn by three horses put to in the usual Russian fashion, with the center horse trotting in the shafts, the other two galloping. The tarantas for the servants and luggage was longer and fitted with a canvas cover, like an old-fashioned prairie schooner.

The road to Kuldja and the Przevalsk is a post road, the charge being three kopecks per horse per verst, with a few kopecks to the driver. A kopeck is one-half cent; a verst, two-thirds of a mile. This includes a tarantas, but we had our own, to save time and trouble in changing luggage at each post house, as we usually did five or six stages a day. The road is both dusty and rough; so rough, in fact, that some quinine pills in a bottle were reduced to powder—although packed in a medicine case in my trunk, the medicine case being rolled in flannel underclothes—while the long lines of camels, often two hundred in a caravan, and the wagons transporting supplies grind the rich soil to the finest powder, which invades everything.

The post houses are very clean and neat, having two rooms for travelers, a large one with a smaller opening off it; the walls are white-washed and the floors of brick, while in the larger room hangs an ikon, a picture of the Tsar and a calendar in Russian of the Singer Sewing Machine Company. At the post houses one can usually get eggs and the brown bread, together with the ever-present samovar for tea. A tariff, of course in Russian, hangs in each room, stating the prices of the samovars, which was usually ten kopecks, and other charges, together with the cost of repairs to tarantasses. A paper should be procured from the Chief of Posts, either at St. Petersburg or Tashkent, giving the right of way over everything but the mails. This is important, as the keepers of the post houses have a supreme contempt for everyone but officers. Although it was midsummer, the windows, as a rule, were sealed by strips of paper pasted over them, and I am afraid we were thought mad in having them opened.

We had intended making Kuldja our starting point, but when in Tashkent were advised to go to Przevalsk, on the eastern end of Issa Kul, a lake about one hundred miles long, as here we were told were the best hunting grounds. Ten days’ easy travel brought us to Przevalsk, where we were very well received by the Governor, and spent five days getting together our hunters, ponies, and other things. Then, just as we were about to leave for the shooting grounds, we received word that shooting was forbidden, and that we must return. We asked permission to cross the border into China at Naryn Kul, a couple of days away, but even this was denied us, and we were delayed for more than two weeks getting the necessary permission from our Ambassador at St. Petersburg.

The day after our arrival, the Governor called upon us, asking us to lunch with him next day, which we did, and while waiting for lunch he had his servant produce several heads of ibex and sheep, which he offered to give me, saying, “Now you need not go to the fatigue of shooting these yourself. If you want more I shall send for them.” It was difficult to make him understand the Anglo-Saxon idea of sport, more especially as every word had to go through the interpreter, who could not understand it either.

The delay was all the more exasperating, as we could see our hunting grounds from our bedroom window, and every day native hunters were bringing in heads of Ovis poli, ibex and roe deer for the Director of the School, who also supplied museums, while everyone frankly admitted that there was no reason why we should not go wherever we wished.

At length, on July 3, after having been at Przevalsk since June 16, we received permission to cross the border at Naryn Kul, and were so glad to be underway once more that we started at once, traveling well on into the night. The next day brought us to Karakara, in the middle of a large plain, where for three months in the summer a great fair is annually held. Hither come the nomadic tribes from considerable distances—Kirghiz and Kazaks, to purchase for the following year all articles which they cannot make for themselves. The Fair is laid out in streets with wooden booths, each street or portion of a street being devoted to one article—such as saddlery, cooking pots, and so on—while on the outskirts of the town a brisk trade is carried on in horses, camels, cattle, sheep and goats. We spent the day here, wandering through the bazaars, and could not but admire the manner in which the bazaar master kept order.

In the evening we traveled on again, and in the morning, just as we neared Naryn Kul, had a superb view of Khan Tengri, rising in a snow-clad cone to 24,000 feet. So high were the neighboring mountains that it did not appear to tower much above them. At Naryn Kul we found a German baron, with one of Hagenbeck’s men, hunting on the Muzart, a river running into the Tekkes just beyond the boundary. Of course, we did not wish to conflict with them, so after a consultation with our hunters, we decided to go to the headwaters of the Kok-Su, a large river running into the Tekkes from the south, as this was the only other place where we would find Ovis poli.

We got away at noon the next day, and soon crossed the boundary, here unmarked, into China or Katai, as it is called, from which no doubt Marco Polo got the name Cathay. The Tekkes valley, where we entered it, is about forty miles wide and covered knee-deep with rich grass, while on either side rise the snow-covered mountains upon whose higher slopes grow forests of spruce. While I have never been in Kashmir, I have been told by men who have seen both, that the valley of the Tekkes far surpasses it, not only in grandeur, but in beauty, and I cannot imagine a more beautiful sight than this valley with the darker green of the forests against the vivid green of the lower slopes, which look as if cared for by a giant gardener, while above all glaciers and snowfields glisten in the sun.

At the end of the next day’s march, we sent back the wagons to Naryn Kul, as the Agoyas, one of the numerous rivers running into the Tekkes, was impassable for them; and for the next four days we traveled eastward down the valley with our stuff loaded on bullocks, getting fresh ones each morning, as well as fresh ponies, so that we could make long marches, not having to think about our animals.

The usual plan was to send ahead to the next village an orderly, or jigit, who would have two yuartas awaiting us—thus saving pitching our tents—with a sheep neatly butchered for our use and fresh transport for the next day. The usual price was twenty-five cents a day for each animal, including the wages of the men.

In describing the yuartas and people I cannot do better than quote William de Rubenquis, a monk, who visited Tartary in 1253, and who in his report to St. Louis of France wrote as follows: “They have no settled habitation, neither know they to-day where they shall lodge to-morrow. Each of their captains, according to the number of his people, knows the boundary of his pasture and where he ought to feed his cattle, summer and winter, spring and autumn. Their houses they raise upon a round foundation of wickers, artificially wrought and compacted together; the roof consisting of wickers also, meeting above in one little roundel, which they cover with white (or black) felt. This cupola they adorn with a variety of pictures.”

On our way down the Tekkes we were met by an escort sent by a Manchu General, Fu Chen, who was inspecting the country, asking us to lunch with him at his yuarta. Of course we accepted, although we knew little of Chinese etiquette save to keep on our hats and not to drink the ceremonial tea until we were leaving, while if he drank his first it was a sign the interview was at an end. The lunch lasted from one until five, with twenty-eight courses and quantities of cognac, ending with music by his private band, and it was well on in the next day before we could think of food again, politeness requiring that we should eat of each dish. No sooner was lunch over and we had reached our yuarta than a servant appeared with Fu Chen’s card and a present of a sheep and some flour and rice; so we prepared to receive our guest, at the same time getting out some American tobacco as a present in return. For his amusement we showed him some books with illustrations, and both he and the Russian aide were much interested in Langdon’s book on the British Mission to Tibet, as Fu Chen had met Younghusband in Kashgar. He at once recognized Younghusband’s picture, and examined over and over again the illustrations of the Sacred City of Lhasa.

We had a good deal of trouble with our packs, as the people had had no practice with the different shaped bundles, their principal experience being in moving the yuartas from place to place, and this they did very well, putting the framework of the yuarta on one bullock and the felt covering on another. The better packers used a hitch not unlike the diamond, taking up the slack from time to time with a short stick. With the horses it was even worse, as the only pack saddles to be found were made to fit the round backs of the bullocks, and this caused the packs to slip badly. As the bullocks do not sweat, their backs do not gall as soon or as badly as the backs of the ponies.

When we reached the Kok-Su, we turned south into the mountains, the path winding up a small stream until we left it to climb in the afternoon to a tableland about 7,000 feet above sea level, where we found the Kirghiz encamped in numbers, with thousands of horses and tens of thousands of sheep. These people live principally on mutton and kumyss, fermented mare’s milk, which we soon got to like and which is mildly intoxicating. Here I spent a couple of days wrangling with the head man about transport for the next six weeks, while Chew killed a roebuck and saw the track of a tiger in a cañon.

Marco Polo, writing about 1275, says of the Tartars: “The women do the buying and selling, and whatever is necessary to provide for the husband and household, for the men all lead the life of gentlemen, troubling themselves about nothing but hunting and hawking, and looking after their goshawks and falcons, unless it be the practice of warlike exercises.

“They live on milk and meat, which their herds supply, and on the produce of the chase, and they eat all kinds of flesh, including horses and dogs and Pharaoh’s rats, of which last there are great numbers in burrows on the plains.”

Pharaoh’s rats no doubt are marmots, which are very plentiful and which spoiled many a stalk, as their shrill whistle put every animal on its guard. From all we could learn, not only on the Tekkes, but at Kuldja, tigers are fairly plentiful in parts of both Russian and Chinese Turkestan, but are very seldom shot, none of the half dozen skins which I examined having a bullet hole. As a rule, they inhabit the great tracts of khamish or reeds, where they prey upon the wild pigs and are usually taken by poison. The Belgian fathers at Kuldja told us that several dozen skins are every year taken in the neighborhood of Urumtse, about four hundred and twenty miles to the eastward.

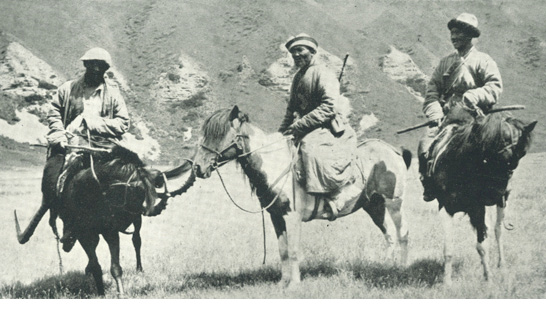

Almost every chief among the Kirghiz had one or two golden eagles, which they used for killing game such as roe deer, foxes, and, I am told, even wolves; but many of these birds seem to be kept more for ornament than for sport, as we never could get the Kirghiz to fly them—although it is only fair to say that the Fathers at Kuldja told us that they had often seen them used. On the plains the common little hawk, like a sparrow-hawk, was often carried on the wrist.On the second afternoon I rode over to’ a place where there were said to be roe, but saw only a couple of does. On the way, while riding along a hillside, we saw a couple of little hawks sitting on a tree some distance off, upon which my men spread out, calling at the same time to the hawks, which at once began flying in circles over us. As at that time I could not speak a word of the language, I could not imagine what was their object, until a little bird was put up out of the grass, when one of the hawks immediately flew at it, but missed it, when the bird darted in between my horse’s feet, as I sat watching the chase. I let the bird remain safely where it was in the grass at the horse’s feet, and we went on, having seven other flights, but in each case the little birds escaped either among rocks or into bushes. On many other occasions when we saw hawks they came to the call of our natives.

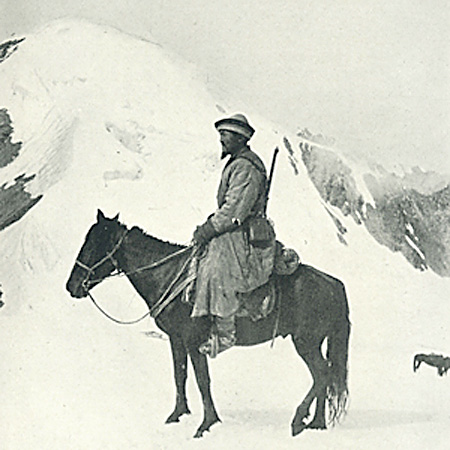

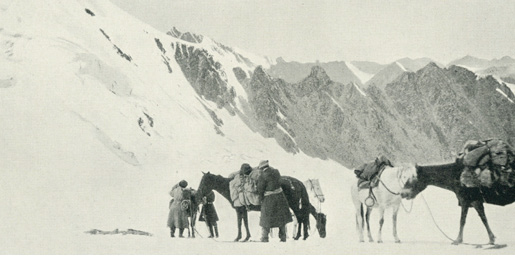

At last I arranged for the necessary horses, two yuartas and a flock of thirty sheep for food, and the next day we were again underway up a narrow valley, whose sides were covered with pine. Up and up we went, until noon, when a halt was made at the last wood, where enough was gathered for the night; then on again over a pass, where the ponies floundered through snow to their bellies until, just as the sun was setting, we dropped into a little valley, making camp at the foot of the glacier in a meadow literally purple with pansies.

After the day’s march, the ponies are not let graze at once, but are tied up for two or three hours. I asked the cause of this, and was told that if a tired pony was turned loose he would take the edge off his hunger and then lie down for the night, while if he rested first, he would eat a good meal. The only time a pony was turned loose at once he did just as they said.

So far we had seen no game, but the next morning a little herd of ibex, high up on the mountain, caused the glasses to be used, only to show that they were all females and young. Further on we passed several skulls of sheep, killed in the winter by wolves, and so felt that at last we were reaching the game we had come so far to find. Another day brought us to a place called Karagai Tash, meaning Stone Pines, from a range of hills whose sides had been eroded by wind and weather until, in the distance, they looked like pine trees. Here we made a permanent camp, turning in that night with hopes high for the morrow; but a snowstorm for the next three days kept us in our tents, where most of the time was spent in bed, as we were well above timber line and had for fuel only a few shrubs, helped out with horse and cow dung.

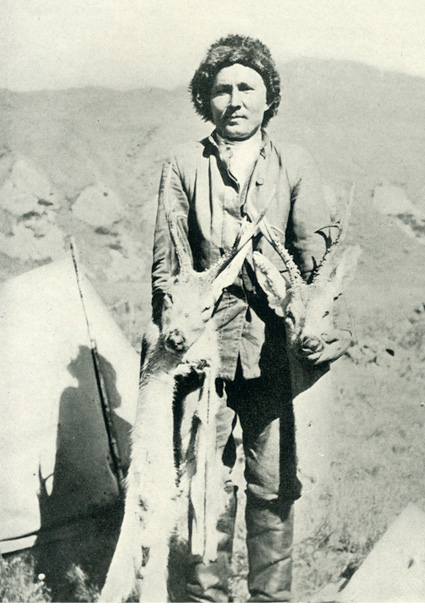

Khudai Kildi, my hunter, was quite a personage. Belonging to the Kara, or Black Kirghiz, he had a profound contempt for Kazaks and common Kirghiz, both of whom he used to order about, often enforcing his commands with a beating from the heavy riding whip he always carried. A fine looking, dignified man of fifty, he stood over six feet and must have weighed over two hundred. On his left arm he carried the scars of a fight he had with a bear when still a young man, and one day, while we were having lunch on the mountain tops, he told me most graphically by signs how he had caught the bear by the ear and killed him with his knife. The sheath knife he carried had a blade about seven inches long, and once a week would have an extra sharp edge put on it, so that he could use it to shave his head.

At last it cleared, and at daybreak I was off with Khudai Kildi in search of ibex. We had not ridden a mile down the narrow valley, when he pointed out a little herd feeding above us on the hillside, only to find that again they were all females. While we were having lunch, about 11 o’clock, Khudai Kildi spied three ibex far off on the sky line among some patches of snow, and we settled ourselves for a long wait, as they were in an unstalkable position, and were not likely to move until afternoon. The fates were kind to us, as they soon got up and walked over the ridge. Leaving the man with the horses, Khudai and I went up another nullah and over the top, but could see nothing of them until we were well down the slope on the far side, when out they walked some distance below us in full sight, but out of range, and it became a case of “belly down on frozen drift” for over an hour in the cold wind that chilled us to the bone.

At last they moved down under a ledge, and we crawled down until I could see one lying just below me a couple of hundred yards away. I was keen to get him, as well as to let off for the first time my new double 360 Fraser, so waiting until I had my wind—we were over 13,000 feet up—I fired, giving him the second barrel as he struggled to his feet, knocking him over the ledge. Letting the other two go, as I saw they were much smaller, we slid down the loose shale to find my first ibex lying dead in a little meadow of wild flowers not a large head, for the Thian Shan, but forty-six inches with heavy horns—very good to begin with.

Another successful day after ibex occurred soon after this on a river called the Musteban, which flowed into the Kok-Su. I had left the main camp for a few days’ shooting and had reached our camping ground near sunset; while the supper was cooking Khudai Kildi and I were hard at work, I with the telescope, he with the glasses, spying the slopes high above us. We were soon rewarded by seeing several hundred ibex, among and above which was a large herd of males. Early next morning we started on our ponies—with a man to hold the horses when the climbing began, as well as to carry the lunch and a thermos bottle of cocoa.

Our ride was a long one, as we had to avoid a rather nasty ford, and had not gone more than an hour from camp when Khudai, looking over a bank, pointed out a couple of roebuck lying asleep on a little knoll directly below me. As we were still a long way from the ibex, I took a shot at the larger of the two, the only result being that his head sunk to the moss, while a quick second barrel accounted for the second. I felt that this was rather a good beginning. Covering them with a great coat to keep off vultures, we kept on until we could see the ibex among the rocks on the other side of a great basin. Here we left the horses out of sight and placed the man where he could signal if the herd moved. The climb up the sliding shale was hard work, the last couple of hundred yards being through deep soft snow; but at last we reached the top and began our stalk on the ibex lying among the broken rocks far below us. Very carefully we made our way down, an occasional look with the glass showing the man where we had left him. This side of the mountain was broken by small cliffs about twenty feet high, but quite as effectual as if they were much higher. At last our descent was blocked by a small ibex, so back we had to climb, almost to the top and down another chimney. Carefully looking over the rocks, we saw the ibex, fully forty in number, lying about the rocks.

For half an hour we in turn used the glasses to pick out the best heads, far from an easy job when an inch or two makes such a difference, and decided on a little bunch of six that were directly below us. Of these I chose the two which to my mind had the longest horns, and then asked Khudai’s advice in a whisper. He took six little stones, arranging them in the same positions as the ibex were lying, and chose the two which I had picked. Taking a fine sight, as they were almost directly under us, I got the first one with the right barrel and wounded the second as he was dropping out of sight over the cliff. It took us some time to get down to the first ibex, which had never moved—a lucky thing, as if he had moved at all, he would have rolled some thousand feet further down. As it was, we had a hard time getting off his head and skin on the narrow ledge.

By this time it was well on in the day, and the other ibex could be seen very sick, lying under a rock some distance away at the foot of a high wall of rock. He heard us coming over the sliding shale, but was too weak and stiff to climb the face of the cliff, although he made a gallant attempt.

Our lunch tasted very good about 4 o’clock, after we had struggled up the mountain and down the other side with our heavy loads, and we reached camp at 7 o’clock, picking up the roebuck on the way.

The first ibex measured 43 3/4 inches, the second 46 1/2 inches, while the roe were 13 7/8 and 12 1/2 inches.

Of course, we were very anxious to get sheep, of which a few were still to be found on the rolling plains to the eastward, and after much hard work and some weeks devoted to them, Chew got a fair head, while I was unsuccessful, as I could not get within shooting distance of the only bunch of rams I saw. The rams were very wild, and at this time of year were in little bands by themselves, usually occupying such a position that they could not be approached nearer than half a mile, often not so close. I think their wildness was due more to danger from wolves than from man, as they were seldom hunted by men, but were continually disturbed by the very large wolves which abound in this part of the mountain, while the numerous skeletons of old rams showed the toll the wolves took. I have heard it said that if a wolf can get within eight hundred yards of a ram he could run him down.

The wolves were much like our timber wolf, although some were darker, and several times we saw, among the horses, yearlings and two-year olds, whose flanks and hindlegs had ugly wounds. The old rams are the easiest prey for the wolves, as the great weight of their horns causes them to sink deeper into the snow or bog, and although I kept a sharp lookout, I never saw the skeleton of a ewe or young ram. This would be explained to a certain extent by the fact that the heads of these would not be so easily seen. We saw numerous ewes and young rams which were comparatively tame.

Chew afterward got a very fine ram with horns 55 inches on the curve and 49 inches from tip to tip. I noticed that this animal had, as usual, very thick skin over the nose, no doubt as a protection in fighting; and in Kuldja I also noticed that the rams of the domestic sheep kept for fighting had this feature very highly developed. These rams were kept solely for fighting, just as game cocks are in other parts of the world; and one morning we offered a prize for the best ram. The rams, with their handlers, accompanied by numerous backers, soon arrived and were placed about twenty yards apart, being let go at the same time. As soon as released they ran at each other with surprising speed, coming together with great force and a loud crash; then, of their own accord, they backed further away, until forty yards separated them, when they would again come together, repeating this until one was groggy, which usually occurred after four or five rushes.

For the next two weeks we hunted on the headwaters of the Kok-Su, some of the time being storm-bound or unable to hunt on account of the clouds being low on the mountains. During this time I shot six ibex, the best head being fifty inches, while the smallest was forty-six. I could have shot a great many more if I had wished to do so. This was not as well as I should have done, but I was very unfortunate in having my glasses washed away while crossing a river, leaving me only the big telescope, which I could not use for quick work, and often I was not sure of getting the best head from a herd of ibex about to move off, as the difference between fifty inches and fifty-four inches is not easily detected at two hundred yards.

By this time our ponies were very footsore and thin, and we decided to go down to the Kirghiz encampments to renew our supply, and once more our men were reveling in kumyss, while we were forced, from politeness, to drink the tea offered to us as a delicacy. This tea is compressed into bricks about nine inches long by five wide and a couple of inches thick, a piece of which is cut off much in the same way as plug tobacco. The tea itself is quite good to Western tastes, but when a lump of salt and some rancid butter is added to the brew, it leaves much to be desired.

We spent a week at this camp, which was on a river called Jilgalong, once a famous place for wapiti, but now full of the immense herds of horses and sheep that the natives were pasturing here. Our camp was beside a river, running clear and cold, which should have contained trout, but, like all rivers running from the glaciers into the Tekkes, had no fish. The only game was roe deer, of which we shot several, usually by driving them up one of the numerous nullahs. These roe are a much larger animal than their western relatives, standing from thirty to thirty-four inches at the shoulder, with horns about fourteen inches long. There were some black game scattered among the hills, but without a dog it was useless to try to find them. In the scrub bordering the Tekkes, and more especially on the islands in the stream, there were plenty of pheasants, similar to the common English variety, with a white ring around the neck. On the plains there were a few bustard, both great and small, but very few ducks or geese.

We were very much disappointed in not finding wapiti in Jilgalong, where ten years ago there were plenty, but owing to the constant hunting of this fine stag for its horns, they are rapidly being killed off. The horns, when in the velvet, are in great demand among the Chinese as medicine, to be used by the women at childbirth. A large pair brings as much as $50, while the skins bring a good price at all seasons of the year.

After a consultation with Khudai, we returned to the Kukturek, where we spent a couple of lazy days, most pleasant after our hard work of the past weeks, loafing about camp and shooting pheasants in the afternoon, while he looked up a friend of his who knew this part of the country.

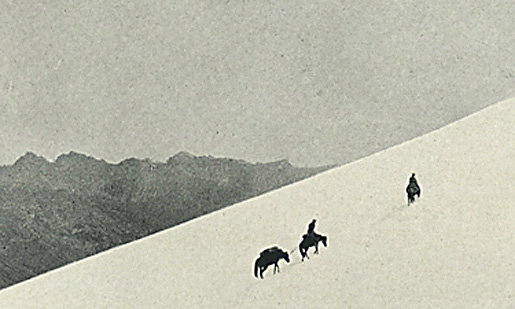

A couple of very long days found us on the headwaters of this stream, where we were to leave our camp, and, taking a few men, were to cross an immense glacier to hunt in a country seldom entered by natives.

For two days a heavy storm kept us in camp, but it cleared in the evening, and the third morning found us under way at dawn, so that we might cross the glacier before the heat of the sun should melt the new snow covering it. We had much trouble in crossing the immense crevasses, whose black depths were far from pleasant to look into, but eventually reached the summit, and had begun our descent of the other side over steep rock slides, when the clouds, which all day had been low, descended, leaving us helpless. At last they lifted, and we were just moving on, when a huge section of the mountain just in front of us gave way, coming down in an avalanche, which narrowly missed the leading ponies. The noise was deafening, and we were much relieved when the dust lifted to see our men safe.

Down we went around a shoulder of the mountain, where high above us the men could see with the naked eye, and we with the glasses a large herd of ibex on the sky line. Chew won the toss, while I waited with the outfit, where I was to see an example of good luck often dreamed of, but seldom realized. It was 1 o’clock when he left, and for the next two hours we watched him with his hunter slowly climbing up the steep grass slope, occasionally shut from view by heavy squalls of hail and sleet. At last, with ‘the big glass, I saw that owing to the nature of the ground, he could not get within shot, and was wondering what he would do when the entire herd, numbering about sixty male ibex, suddenly got up and moved rapidly away from him, only to turn quickly and charge in a body to exactly where he sat crouched behind a rock, passing within twenty yards of him. Time after time his double 450 roared out, the reports coming faintly to us. After seeing this, I moved down the valley a couple of miles, to camp on the first piece of ground that was fairly level. Long after dark Chew got in with three good heads, and with every chance of picking up three more, which he did, in the course of three days, his best heads being 54, 52 1/2 and 50 inches, the last with a spread of 46 inches.

At daybreak next morning I left him with my kit on two horses and with four men to cross another mountain to a place where our guide said there were wapiti. The next evening, after a long day over the roughest country I have ever seen, saw us camped in a long, narrow valley, with many nullahs running into it, whose sides were covered with grass, having here and there wide strips of pine or poplar. By the time I had pitched my little shelter tent and cooked supper, it was 9 o’clock. Four the next morning came very quickly, and soon after we were off in the dark through the dripping underbrush to a place part way up the grass slope, where we could see the opposite side of the valley when day broke. For a quarter of an hour we sat shivering in the cold wind which blew over many miles of ice, waiting for the day, and as it slowly brightened in the east, we could make out with the glasses two little bands of wapiti and a single one that we saw had horns, the others being hinds. Before it was light enough to use the telescope, they had all gone into the timber, while we got back to camp for breakfast, just as the sun shone on the snow-covered peaks far up the valley.

As the river in the canon would be in flood toward evening, we moved over at once, getting everything wet in the rather villainous ford, and then sat down to wait until evening, when we would go after the stag. The lay of the land was such that we had to wait until the wind blew down the canon, which we knew it would do as soon as the sun got near the mountains. At last the longed for change came, and we were off, reaching the place near where the stag had gone into the timber, as it was getting dusk; but he had not come out yet. However, he soon walked out near us, when we saw to our disappointment that he was a small six-pointer—that is, three points on each horn—and what was worse still, in the velvet, although it was now the first week in September. For a week I repeated this proceeding each day, but without seeing a shootable stag, and often no stag at all, while we could not move further up or down the valley, as the water was still too high.

The long days sitting in camp, doing absolutely nothing, as I had read and reread all our books, and without a soul to speak to, as my Kirghiz was very limited, got on my nerves to such an extent that, after eight days, we left, reaching the camp where I had left Chew on the evening of the ninth day. Here I found quite a monument with a large white stone on the top, on which was cut a very good likeness of an ibex, with the inscription, “B.C., 1909. VI.” and written on it in pencil a message saying that he had gotten six good ibex. Another day saw me in the main camp, where a good dinner was most welcome after the last few days of hard work on short rations.

I was greatly disappointed not to get a wapiti, but to my mind it is doubtful if I would have gotten a fair one even in a month. At Kuldja and on the road home I saw many hundred shed horns, which are exported, to be used as knife handles, and a number of pairs with the horns still on the skull; but among all these there was not even a fair set. At Kuldja I spent much time looking for a good pair, offering a large price, but could find none. However, at the Tekkes the guide presented me with a splendid set shot some years ago, which are the best set Rowland Ward has ever seen, next best being a set 54 inches, shot ten years ago by Mr. Church, the author of “With Rifle and Caravan in Chinese Turkestan.” While in the canon where we went for wapiti I saw the tracks of a bear, but could not find him in the thick brush, where no doubt he was living on wild currants and other fruit, and in all our travels we did not see any sign of leopard, either of the common variety or the snow leopard.

If on starting I had known as much about the country as I knew when we left it, our trip would have been much more successful. I have made no mention of the several mistakes we made. First, we did not know until we reached Tashkent that there is for sale a map showing all the post roads with the distances between stations. If we had known that there was a post road to Kuldja from the north, we would have shot in the Altai first. Secondly, in July and August all the rivers are in flood, and at that time very apt to delay travel until a few cloudy days prevent the melting of the glaciers, thus lowering the streams. Thirdly, that Kalmuks are better hunters than any other tribe, and fourthly, that it seems true that the biggest heads are in the highest mountains.

If I were to take the trip again I should go to the Altai in the north for argali (Ovis ammon), then travel to Kuldja by river steamer and tarantas to shoot in the Thian Shan from about the middle of August until October, engaging my men at Kuldja through the Belgian missionaries there—two most agreeable gentlemen who have met every traveler from Littledale in 1882 until the present time. I should buy all my supplies except cocoa and condensed milk at Vernie or Jarkand, and in Kuldja itself. The condensed milk in Russia is to be found at the apothecaries.

I have made no mention of the great number of ibex to be found in these mountains. Often we saw at one time several herds, each with over a hundred ibex. While the actual hunting of ibex is the grandest sport that I have ever had, one must not forget the frequent rainy days or those on which the clouds were low in the mornings, thus delaying the start until it was too late to make a successful day’s hunt. On days such as these, time hangs very heavy on one’s hands, as it does also in the afternoons on days when we moved camp. Now that I am home, however, I look back with great pleasure on the days spent on the mountains, forgetting the times when we were delayed by bad weather and high water.

Geo. L. Harrison, Jr.

From Boone and Crockett Club’s Acorn Series “Hunting at High Altitudes”

Originally Published 1913