Since boyhood I had heard and read stories about sheep hunting. My favorite storyteller was, and is, Mr. Jack O’Connor.

In my early life as a hunter, I knew I would never have the chance to hunt any sheep species other than the desert rams of my home state. So, I made a promise to look for the best head in the mountains near my home, in Mexicali, Baja California, Mexico—and with a little luck, maybe a chance in the Sonoran Mountains, the same hunting place where O’Connor took his best desert sheep.

First, my goal was to take a better head than that of the celebrated outdoor writer. In the process, I became eager to write hunting adventures too, in the style of O’Connor and Hemingway. This story represents my third attempt to publish in English. The other two appeared in Petersen’s Hunting Magazine Deer Annual in the early ‘80s.

The early ‘70s was the era of the Winchester pre-1964 bolt-action rifles in .270 Winchester caliber. That was my father’s rifle, from whom I inherited the passion for sheep hunting. That was O’Connor’s caliber for hunting mountain sheep—and mine too. The ultra-velocity guns that started to appear in the field didn’t attract our attention those days, almost half a century ago. Back then we didn’t know about magnum cartridges or sheep census and populations.

In those days, we never saw a sheep hunting permit. Once in a while, we heard of a foreign hunter, Mexican or non-Mexican, who came to our mountains and shot one or several animals, ewes included. In some cases, they had a letter from some federal official to permit the “hunting.” O’Connor said that the one he used to hunt in Sonora was signed by a high-range military official. Besides, in those years, sheep hunting had been banned since 1922. These practices have nothing to do with modern management. Those hunters were important or very rich people, not local hunters like me, and I was not alone. Several riflemen from Baja and Sonora had the same passion for mountain sheep hunting, and we all did the same thing: study the sheep’s habitat, organize the hunt, climb the mountains, glass the country, hunt alone without a guide, shoot, skin the trophy, take the game out of the mountains on our backs, and in my case, even mount the trophy and write the story.

I have always had great respect for those solitary early local meat hunters. They didn’t use spotting and rifle scopes, camo dressing, GPS, maps, radio or cell phones, and they never knew any permit or heard about the animal’s population estimations. They hunted for a living; to bring home the bacon. In the process, they took some outstanding heads. That was the case of the All-time World’s Record for desert sheep, the 205-1/8 B&C points credited to Carl Scrivens but taken by a local “vaquero” in 1940, when sheep hunting was still banned. In 1964 the ban on sheep hunting in Mexico ended, but sheep tags were never required for local Baja and Sonora hunters.

Every hunter dreams about a record head. In 1971, my father took a very good ram, a 186 green measurement in the field—bigger than that of O’Connor’s—and I decided not to shoot a lesser pair of horns. Recently, my father’s ram was measured by a Boone and Crockett Official Measurer at 182-4/8 points. With a bit of luck, both heads will appear on the same first page of the desert sheep category of the All-time records book in 2017.

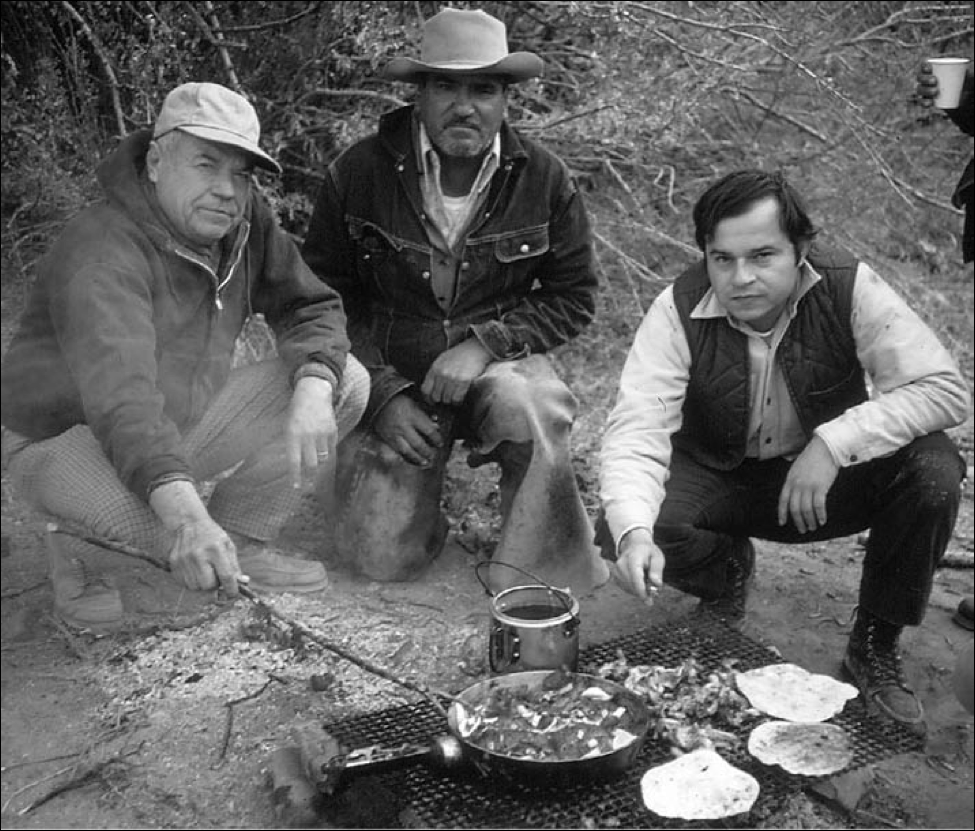

One autumn afternoon in 1972, a professional meat hunter and my father’s friend, Pablo Martinez, told us that in Arroyo Grande, Sierra de Juarez, Baja California, a very big ram was spotted by Policarpio Álvarez Romero, a cowboy for the American cattleman Enrique Jolliff. We knew that country very well, and we knew it could produce trophy-sized mule deer too, so we decided to hunt in that direction. On the 5th of January 1973, we intended to camp in the high desert area of Arroyo Grande, but an early snow obliged us to descend and camp in lower hill country. That natural event put me on a collision course with my ram and is responsible for me being here telling my hunting story.

The next day, my brother Armando and my father took the course of the “in-between” creek. In a north Baja map or in Google maps, you can locate this place between the famous Arroyo Grande Canyon, and the Jaquejel Canyon. Because of that geographical position we named this place the “In-between Canyon.” A friend from San Felipe, Baja California, Dr. Ubaldo Espinoza, and I took the hill route to Arroyo Grande. Soon we found oxidized sardine, tuna and fruit juice cans, typical food of Mexican “borregueros” (sheepherders). I told my friend, “Here is more likely we see sheep than deer.” And my memory took me to the big ram that Policarpio had seen in this area.

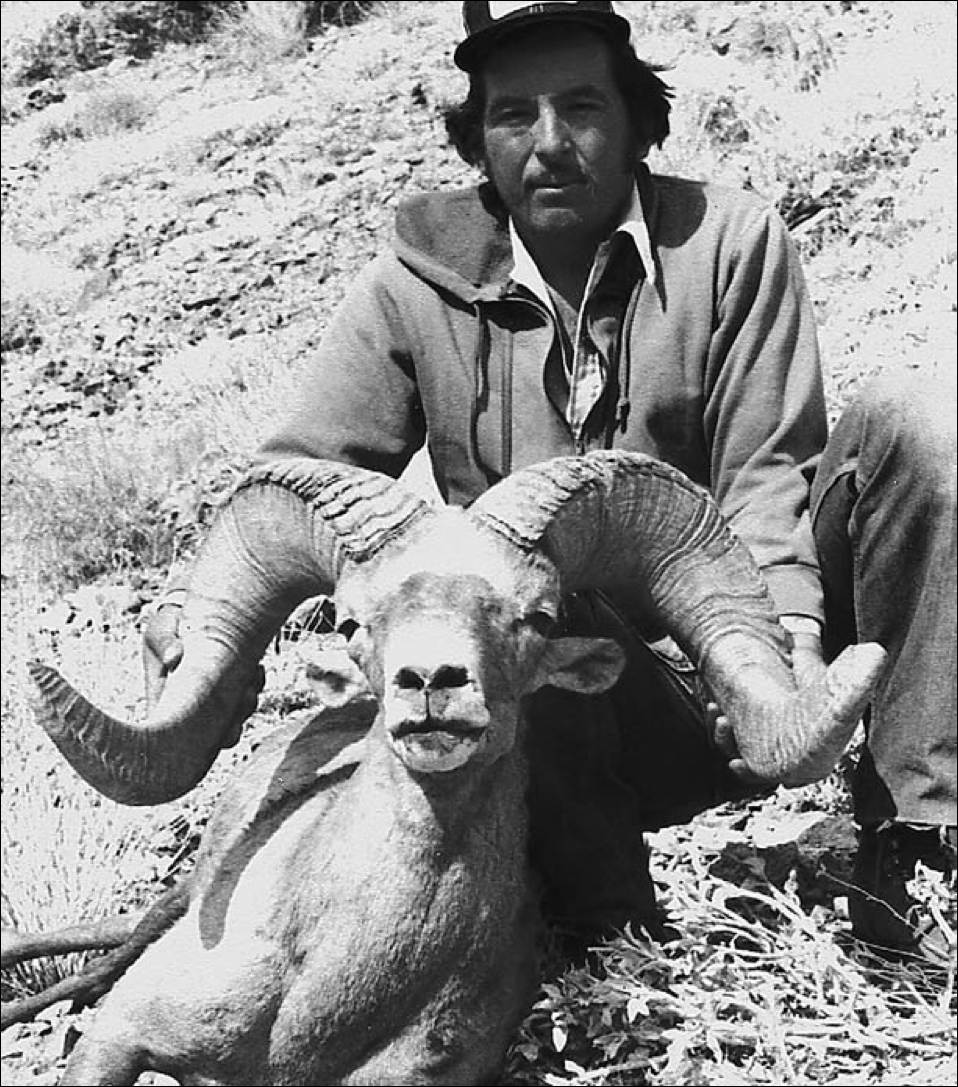

We heard sheep coughing. Later, sheep of all ages filed out of the arroyo in front of us. We glassed them and found no trophies. I told Ubaldo to cautiously walk to the rim of the hill to see if some rams were still there. The doctor approached the spot, holding one of my lightweight mountain rifles, a Husqvarna Sporter in 7×57 caliber, topped with a Leupold compact 4x scope. Then we heard the characteristic hoofs and stone sounds of sheep on the run and waited. One huge ram came out very close, about 80 meters. I shouldered my rifle and saw through the Redfield Wide Field 4x scope the biggest ram I had ever seen.

I decided to shoot that great animal, with a hint of hope that it was Policarpio’s big ram. After the sound of the Silvertip 130-grain bullet exiting the 24-inch barrel, the mountain monarch fell in its tracks. I put my rifle aside and thanked God for the opportunity of encountering such an animal. I inspected it—an old ram, with full and massive horns, very thin neck and worn teeth. The left ear had a scar, maybe a bite of a predator when young. A notorious scar without hair in the top of its shoulder that when skinned showed the main apophasis bone broken by a bullet. Some unlucky hunter overshot and lost “my ram” years earlier. Maybe at close range, too.

Our first field measurement green-scored above 190 B&C points. Forty years later, my ram scored 188-1/8 B&C points. Time takes its toll. The Matson Laboratories of California analyzed a tooth of this animal and concluded that it died at 8 years of age. But its looks misled even a seasoned biologist who opined that it was 16 years old. Rams do not live long lives.

In 1974, the Mexican Federal Program of Bighorn Sheep started, and I ended my sheep hunting career. In the first hunting expedition, and at some hundred meters from the place I shot my ram, American hunter John B. Solo and guide Aureliano Caro found in a cave the skeleton of a huge ram that biologist Ticul Alvarez measured at 202 B&C points. This head has never been officially measured, but it could be Policarpio’s ram. Arroyo Grande produces big ones. In 1978, J.C. McElroy, founder of Safari Club International, took the spread record ram: 29-1/8 tip-to-tip spread.

In 1981, my good friend and guide Jesus Aguiar, guided Bruno Sherrer, an American hunter who took a ram scoring 191-1/8 B&C points in this same place. Some few kilometers south, Javier Lopez Del Bosque bagged a ram that a Mexican official measured at 196 B&C points, but eight years later officially appeared in the records book with 192-7/8. Time took its toll again. During helicopter monitoring in 2010 by the University of Baja California and Dr. Raymond Lee, a huge ram was observed in the Arroyo Grande area again. Witnesses assure that its horns are 200 B&C points-plus. In this same place, I shot my best striped-tail mule deer in 1972. Currently, I’m proposing that this area is declared a sanctuary for deer and sheep.

Between 1976 and 1978, I directed a federal program to build water reservoirs for desert sheep in the north part of the state of Baja California. Following the California and Arizona trend, our work provided several water catch impoundments in the most arid parts of sheep habitat, the San Felipe Desert.

I worked as an environmental advisor for the former Governor of Baja California, Eugenio Elorduy, whose administration created Mexico’s equivalent to the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency. Now, the federal government will be able to manage the wild game for people of Baja California. In the following years, the hunting permits, sheep tags included, will be issued and managed by Baja Californians. An idea that I started to develop in 1973, when I worked in the state government, is now a reality 40 years later. A long war fought and won. During the 22 years of no legal hunting in Baja, the sheep population increased by 56 percent—another positive effect of opposing the over-hunting situation that prevailed in the late 80s. The good news was announced in November 2011 at the “University and Sheep Congress” that I organized with some of the past deans of the University of Baja California.

On February 23, 1996, the Foundation for North American Wild Sheep (now the Wild Sheep Foundation) recognized my efforts toward sheep conservancy with the organization’s Presidential Award in Reno, Nevada. The plaque reads: “For your effort and dedication to bring professional management and long-term survivability to Mexico’s wild desert sheep.” Now, the Boone and Crockett Club has recognized my best sheep taken in a brief period as a sheep hunter (1965 to 1973). I’m very grateful to the Boone and Crockett Club for maintaining the records of our big game animals, archives that are invaluable for researchers and environmental historians.

I hope that these 22 years of no legal sheep hunting in Baja bring new and outstanding opportunities to take trophy desert sheep in my home state. I hope, too, that the chances run equal for residents and nonresident hunters. Only with the participation and support of the local hunters, the future of hunting our great sheep can be sustainable.

Witness the hard-core determination of North America’s most successful hunters. They combined physical conditioning with research, fair-chase ethics, and shooting prowess to seek out and harvest legendary trophy animals.

Thirty hunters. Thirty record-book trophy big game animals, most of them taken without guides on public lands. Thirty epic tales to share back at hunting camp. These are the real-world stories behind some of the top-scoring trophies ever recognized by the Boone and Crockett Club.