We arrive at the answer. And more questions…

In the first two installments of “How far is too far,” we’ve taken a rambling, roundabout journey in an attempt to answer the question posed by my friend Jerry just before a hunt. We expected that our hunt might require shooting at some extended distances, something with which Jerry had not had a lot of experience. He was comfortable to maybe 300 yards or so, but was rightly concerned about shooting at a living creature much beyond that. He did not want to wound a fine game animal, and I admired him for that. Far too often I’ve seen or heard hunters lobbing round after round at a distant elk or deer hoping to hit the hapless creature somewhere — anywhere. That is, in my opinion, beneath contempt.

In part two of our series, we took a detailed look at the characteristics that make some modern riflescopes capable of extreme precision at distances well beyond 1000 yards. These characteristics don’t come cheaply, and is the reason why the best riflescopes carry price tags reaching $2000, $3000, even $4000 or more.

Convincing someone they must drop that kind of money for a black tube with glass on both ends is a difficult sell. There is nothing inherently sexy about a scope. Rifles, though, are something different. They can be works of art, with beautifully patterned wood, deep, rich bluing, maybe even a touch of the engraver’s skill for those with substantial budgets. We caress them, clean them, some guys I know even talk to them. When a hunter finishes dropping a healthy chunk of his income on a rifle, convincing him he must do the same for a riflescope and mounts is a challenge. The temptation is to put as much as possible into a rifle, and save some money by settling for a lesser scope. Don’t do it.

Almost any off-the-shelf modern rifle is capable of excellent accuracy, certainly one-MOA groups at 100 yards. A bit of fine-tuning with different loads and bullets can further shrink those groups. Conversely, the finest custom rifle will only shoot as well as the optics mounted upon it allow.

For many years I’ve worked with New England Custom Gun Service, a long-established supplier of fine long guns, hard-to-find components and sophisticated gunsmithing services. They have told me that 90% of the complaints they get from customers about accuracy can be traced directly to poor optics, cheap mounts, or improper scope mounting techniques. As you might imagine, a well-heeled shooter who just dropped 20 grand on a custom rifle is not pleased to find his new baby is spraying lead like a shotgun. NECG’s advice? Spend more on your optics than you do on your rifle. More so than in any other aspect of shooting, with riflescopes, you get what you pay for.

My friend Jerry had done just that, equipping his .300 Win Mag with a Nightforce NXS 3.5-15 x 50. It was a revelation to him after using a low-end scope for years. “I see things now I never saw before,” he said. Bingo. Step one accomplished.

The NRA Whittington Center, near Raton, New Mexico, is one of the finest shooting facilities in the nation. You can test your rifle shooting prowess from 100 to 1000 yards, and every distance in between.

That is only step one, though. While I pondered how to answer his question, I thought back to my first experience shooting at 1000 yards. I live about three hours from the NRA’s superb Whittington Center in New Mexico, and a couple of years back I had made a pilgrimage there for my first encounter with a 1000-yard range. I arrived brimming with confidence, with the same Nightforce scope Jerry had but mounted on a Sako .25-06 I’d owned for many years. The rifle was exceptionally accurate and consistent, capable of ¼ inch groups at 100 yards, and I had shot a lot of game with it. Nothing much beyond 300 yards, but I figured, if it is that good at 300 yards it must be equally good at 1000.

Setting up on the bench, my first impression was just how incredibly far 1000 yards is. You don’t walk to your targets, you drive. As I prepared to shoot, I became aware of things that I had never noticed before. I could hear — and feel — my heart beating, each thump causing a movement of the reticle off the center circle of the target, a mere speck at that distance. Any excess tension in my hands or arms made steadying the crosshairs impossible. That slight breeze in my face — how would it affect the bullet over a half mile down range? Elevation was no problem — my reticle calculated holdover for me. But simply holding steady on the target was a monumental effort, both physically and mentally.

The author prepares to sight in his rifle at a mere 100 yards, before moving to more demanding distances.

I won’t embarrass myself by reporting how many rounds I shot that day. My groups were measured in feet. Even I could not shoot that badly. Or could I? I spoke with some friends at Nightforce, all experts in extended-range shooting, to help diagnose my problem. We quickly determined there were no problems with my scope or with my rifle.

“What bullets are you using?” I was asked.

“The same 120-grain hunting bullets I’ve used in this rifle for years,” I replied. “They have been very accurate.”

“At what distance have you used them?” they asked.

“I was doing pretty well at the range out to 500 or 600 yards,” I said. “Past that, everything fell apart.”

Ready on the firing line at a “mere” 600 yards. Things went pretty well at that distance. Further downrange, not so much.

“That might be your problem,” my mentor replied. “Most hunting bullets aren’t designed for extreme long-range shooting. They are built to dispatch a game animal humanely at reasonable distances. When you are sending projectiles to 1000 yards or more, you need to be using bullets designed specifically for stability and consistency over long distances. Very few ‘standard’ hunting bullets have those characteristics.”

So, it was back to the reloading bench, the only comfort being that perhaps it wasn’t my ability that was lacking, and I could blame the bullets. It sounded good, anyway.

Fortunately, in recent years some of the most renowned bullet companies, whose products are favored by long-range competition shooters, have invested a great deal of time, money and research into building projectiles that combine extreme-range stability with the penetration, energy transfer and controlled expansion essential to a hunting bullet. They are expensive, but they are also expensive to make.

I have not returned to the 1000-yard range yet, but I have several boxes of shiny new handloads that I intend to try as soon as I get a chance, and I am hoping that they will reduce my groups from broad-side-of-a-barn to something that might be covered with a yardstick.

Accomplished competitive shooters recently broke the “three-inch barrier,” a goal that just a few years ago seemed impossible. New world records of 10 shots in groups of less than three inches at 1000 yards are now being set, and broken, with regularity. It is a result of better rifles, better optics, improved bullets, and the application of technology that enables shooters to more accurately diagnose downrange conditions and analyze their own performance, much like a golfer might use video to identify and correct a hitch in his swing.

This is what targets 1000 yards away look like. Shooting effectively at this distance poses a whole new set of challenges to the hunter and to his equipment.

So what did I learn from my 1000-yard adventure? As Clint Eastwood’s Dirty Harry character famously said, “A man has to know his limitations.” I have an excellent rifle, one of the best long-range riflescopes money can buy, the finest mounts, and now, bullets proven to provide quality and consistency while traveling well over a half mile.

What I don’t have, if I am honest with myself, is the time, and frankly, the inclination, to invest hours upon hours and hundreds if not thousands of rounds in becoming a consistent 1000-yard shooter. There are no short cuts, regardless of what advertising claims may promise you. I enjoy playing the guitar, too, but the only way I’d ever be confused with Eric Clapton is if I went back 30 years, quit my job, and spent every waking moment playing the thing until my fingers bled, and then pushed myself to play even more. A rifle and a guitar do have one thing in common: pick one up only once every couple of months, and you’re never going to be that good.

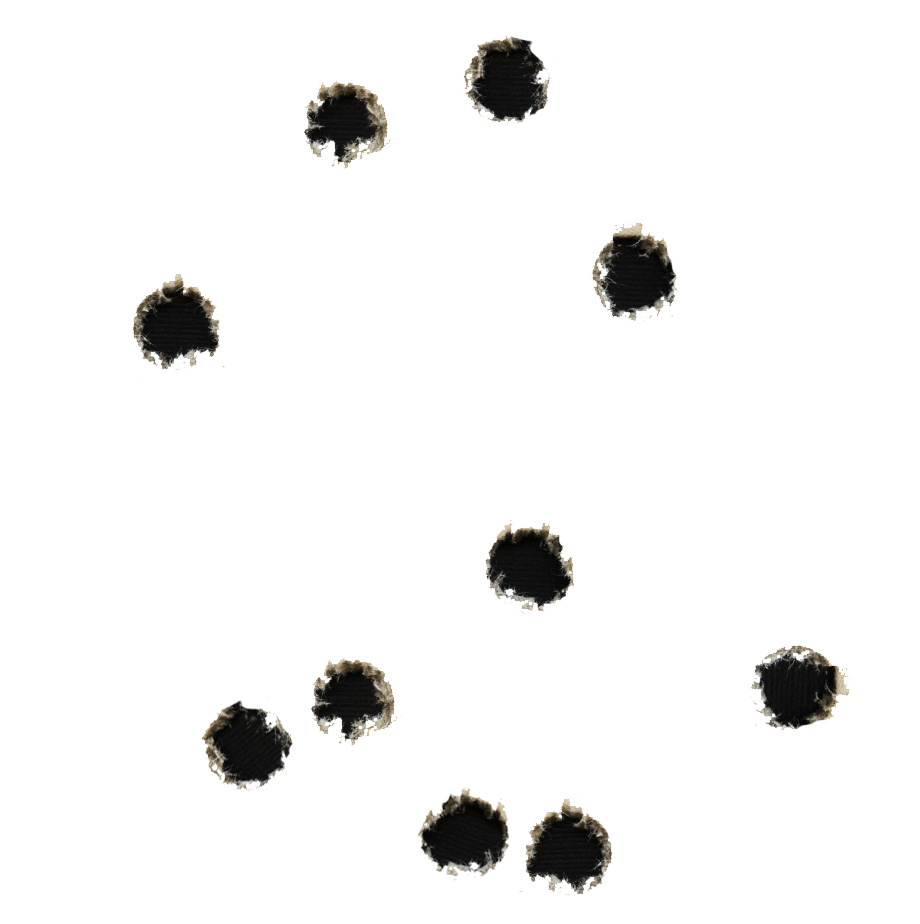

In 2010, Matthew Kline broke the three-inch barrier for the first time with a new 1000 yard 10-shot Heavy Gun World Record. This is his record-shattering group of 2.815 inches, shown actual size. He used a .300 WSM and Nightforce 8-32 x 56 Precision Benchrest scope for this impressive shooting.

In this humble series we’ve looked at the tools and technology necessary to shoot effectively at long distances. We’ve touched upon the ethics of long-range hunting, a topic that has, and continues, to be flogged at length in the hunting media. There are proponents and opponents, and there is little I can, or choose, to add to the controversy surround that topic.

The bottom line is that a shooter/hunter who invests the money into the best possible equipment, and most importantly, then invests the time and effort into constant practice and refinement of his techniques, is infinitely more ethical in his approach to hunting than the guy who shoots four or five rounds before hunting season and pronounces himself competent to take an animal’s life.

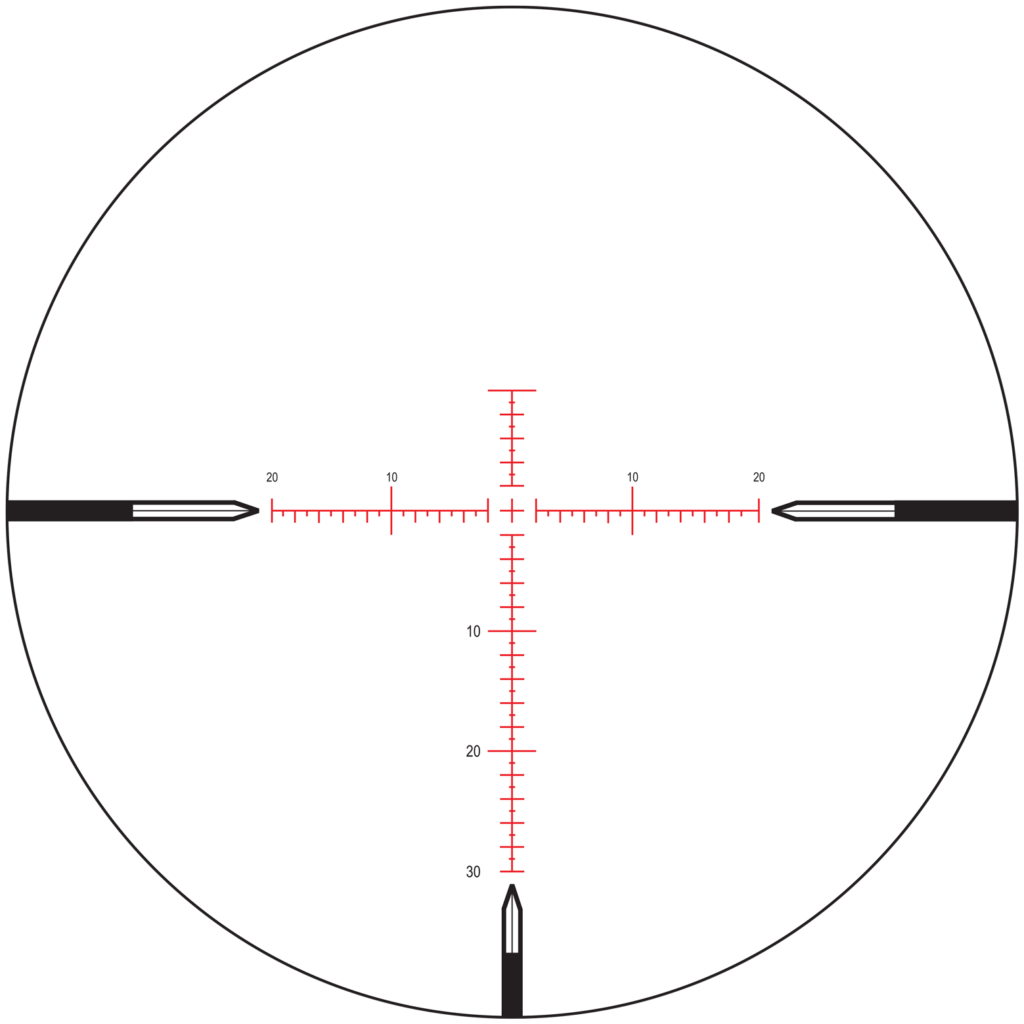

Precise shooting at extended ranges is almost impossible without a specialized reticle designed for the job. The Nightforce MOAR™ shown here is based on minute-of-angle principles, one minute of angle being 1.047 inches at 100 yards. Each vertical and horizontal marking on the MOAR represents one MOA. Minutes of angle are an angular unit of measurement, one MOA being 2.094 inches at 200 yards, 3.141 inches at 300 yards, and so on. When you know the distance to your target, and your load’s trajectory, determining elevation holdover requires only a simple calculation, which can be applied with the reticle itself or by dialing in elevation with the elevation adjustment. Windage compensation also becomes a major concern at long distances, something few hunters study extensively.

A dedicated rifleman (or woman) who knows he can place a shot accurately at 800 yards is infinitely more ethical than the amateur who is wishing and hoping at 300.

I personally will never be an expert 1000-yard shooter. I simply don’t have the time or desire to make the commitment necessary to become proficient at such distances. In short, I’ve realized my limitations. Dirty Harry would be proud.

My forays into long-range shooting have not been without major benefits, though. I know that I have the optics, rifles and loads that are capable of more precision than I am. Having confidence in your equipment, knowing that it will not let you down in difficult circumstances, is of supreme importance when you are about to squeeze the trigger on a trophy animal.

The author had the right rifle and the right riflescope for 1000-yard shooting, but the wrong bullets. At least, that is the excuse today.

The experience and knowledge I have gained have substantially extended my personal comfort level. I am now confident that I can quickly establish precise holdover, eliminating any guesswork, and place a shot precisely in a big game animal’s vitals out to 650 yards. I’m satisfied with that. It is double the distance I felt comfortable with before I invested in top-of-the-line equipment and took the time to learn how to use it properly.

* * *

The sky was showing signs of light. It was opening morning, time to go. Jerry was still nervously waiting for an answer to his question, “how far is too far?” We had talked at length about ballistics, holdover, the effects of high altitude, his rifle and caliber, shooting techniques, all the things that sound great around a campfire but often serve only to confuse when the moment of truth arrives and you slide off the safety.

“Bro,” I said, “there is only one real answer to that question.”

“If you think it’s too far…then it is.”

About the Author:

Tom Bulloch has worked in the optics industry for over 21 years. He has hunted on six continents, doing, as he puts it, “more hunting for less money than any man alive.”

His credentials as a mountain hunter include two ibex, bighorn and Dall sheep, a mountain goat, tahr, chamois, mouflon, and many timberline elk and mule deer. He lives at nearly 9000 feet in the Colorado Rockies, where, he says, “even looking for my car keys is a mountain hunt.”