Three years ago, my lifelong hunting mentor and — conveniently — my Father, George Lampreau, asked me if I wanted to put a Limited Entry Hunt (LEH) application in for any specific unit in B.C. for sheep. I had first set foot in the sheep mountains in 2009, though I had always hunted the general open seasons for mountain sheep. Needless to say, the excitement began to build at the thought of hunting a LEH zone for the first time.

Though LEH or draw-style hunts are the norm across much of the United States, British Columbia offers the mountain hunter a rich and varied selection when it comes to chasing sheep. Rocky Mountain and California Bighorn dwell in much of the mountainous southern regions of the province, with Stones and Dall Sheep inhabiting the northern ranges. While many of the specific regions that call sheep home do have LEH only hunting opportunity, the vast majority of sheep hunting in British Columbia can be done with tags purchased over the counter — what we call General Open Season (GOS).

It may come as a surprise to many of you that I had no reply to my father’s question. Between the amount of GOS sheep hunting opportunities, and my focus on the beginning of my high school graduation year, I hadn’t spent much time daydreaming about draws. Eventually, I told him to pick a random area — if we drew, we drew. Little did I know that the results and the experience of my 2015 sheep season would exceed my wildest dreams and expectations. I was ecstatic when he told me I drew a tag in a region that holds both populations of Stones and Dall sheep, as this meant a chance at either ram was on the table.

The warm days of summer seemed to pass at a crawling pace, something usually celebrated by a high school student, though the suspense was killing me. The hours spent reviewing, acquiring, and packing gear for the trip only added to the excitement. After what felt like an eternity the day had finally arrived; gear for two weeks was packed, and we began our road trip north on July 30th.

After forty hours of travel, we arrived at our destination lake on August 1st, opening day of thinhorn sheep season. Excitedly we ignored typical camp duties and set up behind our binoculars and spotting scopes. Our own impatience was met with reward, as only ten minutes had passed when we spotted several mountain goats in a far basin. This was thematic of the first day, as five more would appear in the first few hours glassing. Eventually, we set up a lakeside camp for the evening and resumed glassing, finding a ram at last light skylined on a giant rock pillar across the lake. Upon pulling out the spotting scope, we knew instantly it was worth another, closer look.

The second morning would be spent finding more mountain goats, which had peaked our interest for a moment as we had both drawn LEH tags for mountain goat in the area. That initial excitement was quickly brushed aside because we knew what the main goal was… these weren’t the snow-white ungulates we were after. Late morning would see us unload the boat and move our backpacking gear into it, and we found ourselves crossing the beautiful turquoise water of one of many lakes dotting this northern country. The water was calm and looked like a stained glass pane, our anticipation rose with every splash off the bow of the boat.

We landed our boat at the bottom of the basin that wrapped around the rock pillar the first ram skylined on. Shouldering our packs we set off on foot, the tribulations of every-day life behind us for the next two weeks. For those who don’t know, the alder and willow of Northern British Columbia can humble even the most nimble, hardheaded of hikers, and within an hour we were reminded of its presence. Eventually, we found a game trail through the alders that followed a ridge up to open heather slopes and ended up finding a high alpine natural spring to camp beside for our second night.

The third morning we broke camp and worked our way into the back end of the basin we had hiked through the previous day. Reaching the bowl of the basin we were expecting to find sheep, the country was as ideal as it could have been. We sat on the front lip of the bowl glassing the surrounding tops of the basin only to find one head sticking up over a rock on the skyline. Soon enough this would turn into a small bachelorette party of eighteen ewes and lambs. Our first sheep encounter up close, they fed and wandered the crest of the valley where we were planning on going until we hiked right up to them. Acting nonchalantly, they were in no rush to leave. It was only after we were on top of the basin beside them, that they wandered fifty yards off the plateau and onto a bluff. We would spend several hours glassing from this plateau, splitting up and covering either end. This would turn out to be a mistake, and at the time I thought it cost us the hunt, leaving us with low hopes.

My father was glassing one end of the plateau overlooking a small glacial moraine lake encompassed by cliff faces. Appearing out of the bluffs below him at 150 yards were two rams, both legal and both exceptional in quality and character. One was long and flaring, the other broomed and heavier. The wind shifted suddenly and began coming off our backs, and by the time I had got over to my father, the rams moved out to 475 yards. In minutes they had moved across the bowl and into the next drainage with the two of us in tow. What took them fifteen minutes to trot across took us forty-five, only to see them two basins over. It was now nine o’clock at night, and we were in low spirits once again. We made our camp right there on the hillside — dejected and unknowing what we were going to wake up to.

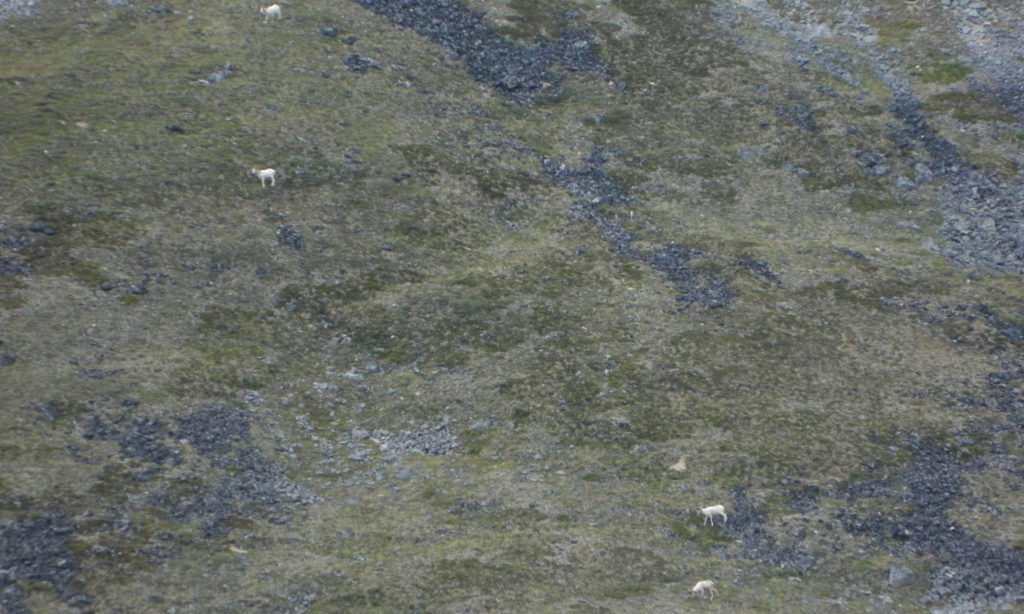

By four o’clock the next morning it was just bright enough to see the different shapes and colours of the rocks across the basin we camped in, and we could pick out several that seemed to have rolled in overnight. As we sat and drank coffee, we watched the white dots move around the hillside, believing them to be the same herd of ewes from the day before. It took an hour for the darkness to lift enough to correct our beliefs, and our discovery was jaw-dropping. A band of eleven rams had moved in overnight, bedding on the hillside across from us. Of the eleven, two were huge, and another three were certainly legal. One of the three was a true Dall sheep, its coat ivory-white down to the tip of its tail, though the largest of the herd was a no-brainer.

To further clarify what I mean by “no-brainer”, without binoculars or a spotting scope at 800 yards across the basin, you could see horns coming over both sides of its nose. Undoubtedly, this is one of the experiences I’ve had hunting that will never leave my memory. We spent the day pinned down in the tent, as the rams knew something was different but didn’t mind enough to take off.

The plan we concocted to close down the distance seemed a bit far-fetched, though we didn’t have any other options. We awoke at three o’clock the next morning, packing our camp by moonlight, and used the red light mode on our headlamps to drop down into the bottom of the basin. From there we cautiously picked our way up through the only passable gully to get onto the side of the basin the rams were on, in hopes they would feed low enough on the mountain for a shot. We set up on a large boulder in the gully and took a range of the hillside above us, leaving us within 350 yards of where the rams were laying the night before.

If you have ever laid in wait for a true monarch of the mountain, you know exactly how fluid time can be, and how slow minutes can pass. It was exactly four minutes past five o’clock that morning when the first ram fed out — the smallest of the group — 312 yards above us. This procession continued, each ram bigger than the last, as they fed onto the open heather slope above us. Soon enough ten rams were above us, between 260 and 330 yards, but the largest of the herd wasn’t there. Time seemed to be dragging by as we looked over the herd, without our target ram in sight. I glanced nervously at my watch, only six minutes had passed though I’d have sworn we had been sitting for hours.

Finally, the lead ram — our target — appeared and began to take the bachelor herd up the hill away from us. They moved uphill swiftly and soon were all 350 yards heading away. I still can’t make sense of why, but the rams stopped, turning back towards us and came downhill once again. Our target ram led the way downhill, back into a comfortable shooting range. He slowly fed his way across the heather slope, now broadside. I was settled on the rock with my dad reading ranges off beside me, both of us fighting nerves to keep calm as things seemed to be piecing together. He whispered, “273 yards, he’s gonna stop and you’ll have a perfect shot. Last one, far left, 273 yards. Think about your shot and relax”. I watched the ram come to a stop in my crosshairs, felt the push of my rifle against my body, and watched the rams legs fold from underneath him in an instant.

If the booming report of my rifle wasn’t loud enough to wake up the valley, I’m certain our yelling was. The build-up of this hunt, the highs and lows along the way, and experiencing it with my father made this the hunt of a lifetime. Covering the 273 yards at a sprint, ground shrinkage was absent. We spent hours drinking coffee and taking in the sunrise next to this fallen king of the mountain before the fieldwork began. If the success of our sheep hunt wasn’t exciting enough and hadn’t provided enough of a story to share, packing the ram out surely added to the plot.

We were in our last basin above the boat when, in the bottom of the valley, we spotted a small black bear. Thinking nothing of the matter we kept trekking across the hillside, loaded with camp, the meat, head and hide, and with legs that were rapidly tiring. We couldn’t have timed it any more poorly, as the small bear happened to be a cub, and the mother was taking it, and its siblings up the hillside. We met in a small fold in the hillside and were caught in between the sow and her cubs. After several warning shots and a few bluff charges, she showed us some respect and moved from a close twenty feet back to fifty, forgetting her cubs in the tree right beside us. We turned and sprinted backwards to give them some distance before reloading, dropping our packs and coming back to the scene of the duel — making plenty of noise and ensuring the bears had left. Conveniently, this rush of adrenaline seemed to give our tired legs a second wind to get out of the valley.

While it is a phrase that is perhaps over-used amongst hunters, this hunt truly became the experience of a lifetime, shared with the best hunting partner I could have. From beginning till end, we had gone through the highs and lows typical of sheep hunting, although they seemed to intensify until our perseverance put us in the right place at the right time. Though the outcome of the trip is a high that I’m sure I will struggle to reach again, I am fortunate to have the rest of my life to attempt it.