The bighorn sheep holds a special place in the global psyche. People travel from all over the world to places like Banff, Jasper, the Greater Yellowstone Area and the mountains of the Southwestern US and Mexico for a chance to see these heavy horned monarchs of the mountains. There are few animals more representative of the high and wild peaks of Western North America than ovis canadensis canadensis, ovis canadensis nelsoni and ovis canadensis californiana.

Amongst hunters, they hold near mythical status. There aren’t many animals that will render an experienced hunter speechless, but produce a picture or mount of a mature, trophy class bighorn, a true “toad”, and you might just see an otherwise hard as nails mountain man cry. For most diehard sheep hunters they represent the pinnacle of achievement, a goal many will spend a lifetime in pursuit of.

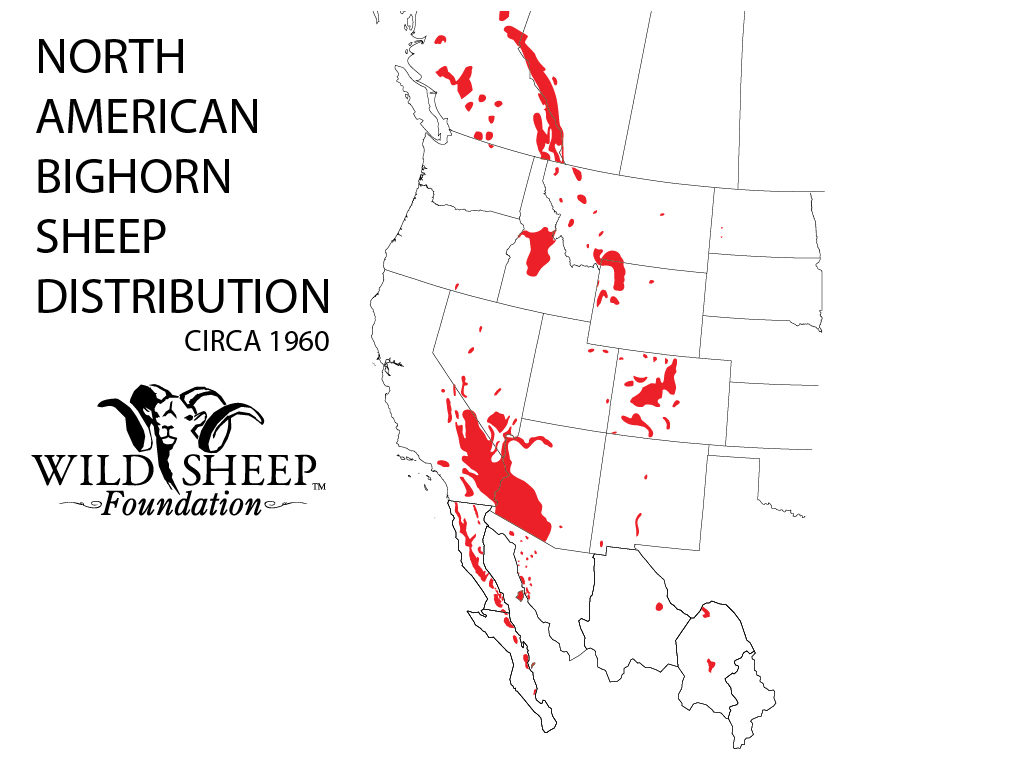

Yet despite this near ubiquitous fascination, North America’s history with the bighorn was not always marked by respect and admiration. Of all wild sheep species, the bighorn has had the most tumultuous ride with the expansion of civilization. The settling of the West brought habitat destruction and usurpation, unregulated market hunting, and perhaps most importantly the spread of infectious diseases carried by domestic livestock that wreaked havoc on wild sheep populations. The distribution maps below paint a very clear picture of the precipitous decline in bighorn populations and distribution over the span of just one century.

As you can see from the last map, the efforts of the WSF, WSSBC and their various conservation partners and affiliates have, in only 56 years, achieved massive success in re-establishing populations in many historically native ranges. But the work is not done. Far from. Although market hunting is a distant memory and habitat protection and restoration is one of the true successes of the modern hunter led, conservation movement there still exists a significant and distinct threat to bighorn populations: infectious disease transmission. As noted above the spread of infectious disease from domestic livestock, sheep and goats specifically, was and still is one of the biggest perpetrators of wild sheep population decline and die-off. Many otherwise successful conservation efforts have been hampered by disease outbreaks that spread like wildfire in wild sheep herds.

This is not an isolated issue. It impacts our populations here in BC, in some of the most historically significant native ranges, and many of the restored or enhanced populations in the lower 48 that the WSF and its chapters and affiliates have worked so hard to bring back from near non-existence. In BC, the most recent documented die-off of wild sheep was in the south Okanagan in 1999-2000. The bighorn population declined from 450 to 150 after contact with domestic sheep. That’s a roughly 65% die-off and can only be described as catastrophic. This is happening in pockets all over North America, in virtually any area where domestic sheep and goat livestock operations come into contact with wild sheep populations.

This joint issue statement from the Wildlife Society and the American Association of Wildlife Veterinarians clearly outlines the dire risks, challenges and utter importance of managing this issue. Both for the future of wild sheep populations and by extension, the future of sheep hunting for generations to come:

“Wild sheep are susceptible to a variety of diseases that affect herd viability. The most important diseases affecting wild sheep populations are respiratory infections that result in pneumonia. Bacteria of the family Pasteurellaceae (Pasteurella multocida, Mannheimia haemolytica and Bibersteinia trehalosi), and Mycoplasma ovipneumoniae are the most frequently isolated respiratory pathogens from wild sheep with pneumonia. Pneumonia caused by these organisms often results in the mortality of a large proportion of the population (Cox and Carlson 2012) across all age classes (referred to as an all age epizootic or die-off) and is typically followed by enzootic disease with multiple years of lamb mortality from pneumonia (WAFWA WHC 2014). This pattern of pneumonia in wild sheep has been documented in more than 70 peer-reviewed scientific publications.

Incidences of pneumonia-related die-offs are frequently associated with the presence of domestic sheep and goats (George et al. 2008, Wehausen et al. 2011). Controlled research studies have confirmed that both Mannheimia hemolytica and Mycoplasma ovipneumoniae are transmitted to wild sheep upon contact with, or proximity to, domestic sheep (Besser et al. 2014, Lawrence et al. 2010, Wehausen et al. 2011). Domestic sheep and goats commonly carry these disease- causing organisms which typically cause few deaths and little illness in domesticated adults and lambs (Martin 1996, Gilmour and Gilmour 1989). Contact between animals from range use overlap on public land and forays of wild sheep to nearby domestic herds on private in-holdings and visa-versa, is the crux of this wild-domestic animal controversy. While not all outbreaks of pneumonia in wild sheep have confirmed contact with domestic sheep or goats, the preponderance of scientific evidence shows that association with domestic sheep and goats poses a significant threat to the continued conservation and restoration of wild sheep populations.”

Solving this issue and ensuring healthy, stable bighorn populations are not a distant memory we can only tell our grandchildren about will take multilateral and innovative actions from wildlife managers, provincial, state and federal politicians, agricultural industry representatives and of course the hunting, conservation and environmental community. In the recent Sitka film TENDOYS, the Montana FWP brought one of these innovative actions to bear on a particularly hard hit population after multiple failed attempts to augment and restore the herd. As discussed in Call to Action in the Mountain Life column this month, it’s this kind of action and innovative thinking from all parties that is crucial to the future of many conservation efforts, regardless of species.

The video below provides a phenomenal overview of the issues at hand and the challenges the bighorn faces, specifically within the Greater Yellowstone Area, and generally across the ranges where bighorns come into contact with domestic sheep and goat operations. The 17 minutes it will take to watch this documentary is worth every second.

Whether you’re an experienced sheep hunter, an aspiring one, or just hope that someday your kids or grandkids will have the opportunity to hunt these iconic animals, this issue is the issue that will make or break the ongoing success of bighorn populations across the West.

Adam Janke

Editor in Chief