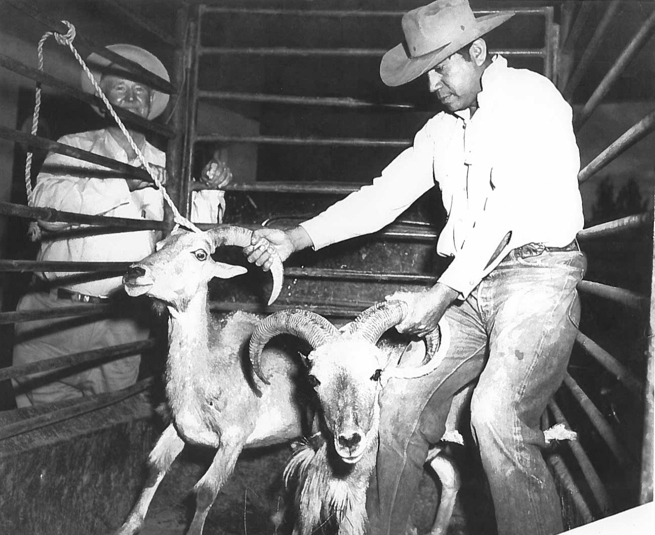

My parents have a framed photo hanging on the wall of their living room. It’s a scene from the 1950’s of a young cowboy in a stock trailer, his strong dark hands firmly wrapped around the horns of two gaunt Barbary Sheep (Aoudad). His boss, standing outside the trailer, is watching intently as the young man holds on to the beasts. The young cowboy looks away toward the floor of the trailer as the photo is taken. Those two sheep however, native to North Africa, foreigners to the hardscrabble realities of the Big Bend Region of West Texas they found themselves in, are looking directly at the camera. Their eyes have a wildness about them, an uncertainty towards what lay in store. They had no way of knowing the role they would play in the population of their species throughout the region, but those first sheep, along with the ranchers and eventually hunters who helped facilitate them, set the groundwork for what would later become a thriving business for landowners and hunting guides in West Texas. There’s a lot going on in that 8’’x12’’ oak frame.

The young cowboy is my grandfather. I’ve seen the picture countless times. It has been hanging in the same spot for years, but I always find myself staring at it, imagining life back then on that desolate mountain. In that dusty corner of Texas, he lived disconnected from the rest of the world, but the longer I stare, the more I am convinced that he knew a stronger connection to something so much more meaningful. Something lost to us, in our world of Wi-Fi and social media.

February 2018, New Mexico Barbary Sheep Hunt

I hiked three miles in the dark to get to this spot undetected. Guided by my headlamp and handheld GPS, it didn’t take as long as I was planning, and I’ll be sitting in the dark a while waiting for the sun to come up. I’ve seen sheep on the mountainside across the canyon from me on past scouting trips, but I haven’t seen evidence of another creature in this country for seven days. I’m due.

It’s a little after 06:00, and I’m wishing like hell I had spent the extra money on a better insulated, warmer jacket. It won’t be long till I go numb, but until I reach that point, every inch of me is screaming, begging to be taken somewhere else. The desert wind in February has a way of stripping every bit of warmth off your body, but I have a sheep tag burning a hole in my pocket. So, my knees are pulled up to my chest in an effort to retain body heat, and I’m hunkered down at the base of the largest yucca I could find on this sandblasted mountainside, using it to block the wind. The 50 mph gusts through its daggers create a hissing sound that silences everything else.

I’ve been trying to find a comfortable way to sit on this bed of lava rock for over an hour, there isn’t one. Each time I shift my weight, the sharp stone digs deeper into my back. The blood- crusted glove on my left hand is proof of just how unforgiving these mountains can be. I tripped yesterday on the way down and the mountain gave me a three-inch cut across my palm, a souvenir I’ll get to take with me to remember the fall. The laceration probably needed stitches, but I was too far from cell service to call out, and the nearest store was going to cost me a day of an already time constrained hunt. Luckily, I had plenty of gauze and whiskey back at camp. I may have taken more than the recommended dosage, but when you’re alone in the desert, nobody cares if you howl at the moon — Coyotes aren’t very judgemental.

Behind my back in the distance, the sun is peeking over the Guadalupe Mountain Range, and the tallest peak in Texas is casting its intimidating shadow over the Southern tip of New Mexico just as it has done every morning for eons; long before man-made, imaginary lines were brought into existence. The explosion of light across the landscape exposes the havoc that the sweeping winds are wreaking across everything in sight. The violent gusts are contorting everything in this canyon to their will. The usually proud Ocotillos that litter this canyon bend at the command of the invisible force.

The promises of a New Mexico weatherman aren’t usually worth a damn, but when he says the wind is going to blow, well, you can take that to the bank. I had been toting my bow the first few days of the hunt in hope of increasing the excitement of my first sheep harvest by stalking within bow range to do it, but today’s forecast of gusts into the 60 mph range changed my mind. My Bowtech was going to have to sit this one out at camp, if I had a camp left to go back to.

The morning light had uncovered the top half of the mountainside across from me. My position lay cloaked in darkness, and it would stay that way until the mid-morning sun rose high enough in the sky to uncover me. A perfect spot for glassing. I was so focused on all the beauty before me that I almost didn’t see him.

The sun glinting off his horns is what initially pulled my attention away from everything else. He wasn’t moving fast, and his position on the mountain had me wondering if he had been there the entire time, hidden in plain sight. How had I missed him until now? Some quick adjustments of my spotting scope and I was able to focus on him. His long, flowing chaps were moving with the wind like a dark brown curtain sweeping the desert floor beneath him. His battered Roman nose proudly displayed scars from his battles throughout the years, and the fact that I could see them from across the canyon is either a testament to my spotting scope or to their depth. Probably both. He was the mature ram that I had hoped to have a chance at harvesting when I started planning this hunt, months before.

I am so caught up in his display of awesomeness, that I almost forget the reason I’m sitting on this mountain shivering, with lava rock jammed up my ass. I pull my rangefinder out of my jacket pocket. My right hand is shaking uncontrollably as I bring it to my eye, I’m not sure if it’s from the biting cold or a by-product of adrenaline brought on by the ram across the canyon. 326 yards. I breathe a sigh of relief as I double and then triple check the distance. I’m accurate out to a farther distance, but the wind has me second-guessing my abilities. I reach across my body with my right hand to grab the Remington Model 700 nestled in the rocks beside me when I get the feeling he’s watching me. I set the rifle in my lap and crane my neck till my face presses against the black eyepiece of my Vortex scope. Sure enough, he’s staring in my direction, I

don’t dare move. How could he have seen me? I made one small move with my right arm, and he wasn’t even facing my direction.

After a two minute staring contest, he shifts his gaze away from me, takes a few steps towards a tall yucca, and beds-down beside it. Apparently, I’m not the only one in this canyon who thinks they make fine windblocks. As he bends forward to shift his weight onto his front knees placing them on a bed of lava rock, I can’t help but notice how unphased he is by this harsh environment. He’s perfectly at home, and looking my way again.

He’s played this game his entire life, undoubtedly dodging death-by-hunter year after year. Rams on public land don’t get to be his age if they aren’t extremely efficient at escaping danger. I won’t have an ethical shot opportunity until he stands up, exposing his vitals, and he doesn’t seem to be in any hurry. I can’t so much as reach for my pack to grab a snack for fear of giving away my position, and the lava rock beneath me hasn’t gotten any softer. It’s going to be a long day.

I have plenty of time to think, and as my mind wanders, it lands on that photo from my parents’ living room. The young cowboy in the picture has been dead fifteen years now, but I was given his name and I try to do right by it. I wonder what he would say if he could see his grandson curled up on this rock hiding beneath this cactus. He’d laugh, I’m sure. What would he think of the world he left behind? It has changed so much since that day in the stock trailer. Those two sheep are obviously gone, as well. Their bones have long since bleached in the sun, scattered across the desert floor by coyotes and West Texas windstorms. But like me, their descendants live on. One of them is 326 yards away, taking a nap.

After at least two hours of laying down beside that yucca, the ram finally pushes the weight of his old, scarred body up off of the razor sharp rock he was using as a bed. He stands and turns his gaze away from my mountain, giving me an opportunity to remove the straps of my pack from my shoulders. I’ll need the added height from my pack to set my rifle on to make up for the angle at which I’m sitting. As I peer into the scope attempting to locate him, I feel the cold, walnut stock pressing against my cheekbone. I’ve read enough to know that synthetic rifle stocks are superior to wooden rifle stocks, more accurate and lighter, for sure. But, all of grandpa’s rifles that I remember from my childhood had wooden stocks, and I’m a little bit nostalgic.

After a moment of finding my bearings through the scope, my eye lands on the animal walking across the mountainside. I stay on him until he finally stops, giving me the perfect shot. I line the scope up where I need it, compensating for the wind and the distance between us. I take a deep breath and slowly squeeze the trigger. The sound from my 7mm Remington Mag rings out across the canyon. Neither of us hear it. We both feel it. The punch from the recoil takes my eye away from the scope, but not before I see the dust fly off his light brown coat as my bullet connects. When I gather myself enough to look back through it, I see him lying on the mountain, dead. I slide the bolt action of my rifle back so I can place the spent casing in my pocket. The familiar smell of gunpowder fills my nostrils, and my hands are shaking. It has nothing to do with the cold.

As I hike across the canyon to him, I’m hit with all the usual emotions that come with taking an animal’s life. I feel appreciation for the animal and the meat it will provide, mixed with the relief in knowing that I have spent my last morning on the edge of a mountain freezing in the dark, for a while. I feel remorse for having taken the life of an awesome creature, but as I walk up on the ram and grab his horns and look into those eyes that only moments before were so full of life, I’m hit with something new. Validation. Not because of the dead animal at my feet, but because of my journey to get here.

I’m not articulate enough to try and explain exactly why I hunt. Justifying why I feel the need to go out and take the life of an animal that did nothing to me is a tall order, and if I tried, those morally opposed would stand on their high ground and pick my explanation apart anyway. The answer to that question lies in this ram whose horns are in my grasp, and how even though I haven’t seen my grandpa in 15 years, I can feel him with me in this moment, somehow. I can’t put it into words. Maybe I’m not supposed to be able to. Trying to rationalize this moment to a group of people who aren’t looking for the common ground that I’m trying to meet them on would cheapen it somehow. If being misunderstood is the price I have to pay for the freedom I am feeling in this moment, I will pay it every time.

I will say that standing on this windblown mountain, reminiscing on a week of sheep hunting and isolation, I have forgotten the burned out, disconnected feeling I get from “civilization.” Getting out here with the cactus and the sheep allows me to step out of the cage that I have let the world build around me. The wind dissolves my problems for a bit — I can be Me.

It will take a couple of trips to get all the meat packed out of this canyon and back to camp, but when it’s all over and my coolers are loaded in the bed of my pickup ready for the three hour drive home, it will be the end of an awesome adventure. One that started almost seventy years ago, in black and white.