They saw the buffalo after killing the elephant. The PH switched off the engine and eased out of the battered olive Land Rover, carrying his binocular.

His hunter slipped out on the other side, and one of the trackers in the back, without needing to be told, handed his 300 down to him. The hunter pushed the 220-grain solids into the magazine and fed the 200-grain Nosler into the chamber, locking the bolt and setting the safety as the PH glassed the buff.

It was nearly sunset, and already in the back of the Land Rover lay heavy curves of ivory, darkened and checked by decades of life, the roots bloodied. They had found the old bull elephant under a bright acacia late in the afternoon, having tracked him all day on foot. He was being guarded by two younger bulls, his askaris; and when the hunter made the brain shot, red dust puffing off the side of the elephant’s head, and the old bull dropped, the young ones got between and tried to push him back onto his feet, blocking the insurance rounds. The bullet had just missed the bull’s brain, lodging in the honeycomb of bone in the top of his skull, and he came to and regained his feet, and they had to chase him almost a mile, firing on the run, until he went down for good. By then it was too late to butcher out the dark red flesh; they left that task until the morning when they would return with a band of local villagers and carry out everything edible, down to the marrow in the giant bones. They took only the tusks that afternoon; yet when they finally reached the Land Rover again they were very tired, pleased with themselves, and ready only for a long drink back in camp.

So, when on the way to that drink the PH spotted a bachelor herd of Cape buffalo (with two exceptionally fine bulls in it), it was all a bit much, actually. He motioned his hunter to come around behind the Land Rover to his side, and crouching they worked behind some low cover toward the bulls, the mbogos.

The first rule they give you about dangerous game is to get as close as you possibly can—then get 100 yards closer. When the PH felt they had complied with this stricture, to the extent that they could clearly see yellow billed oxpeckers hanging beneath the bulls’ flicking ears, feeding on ticks, he got his hunter into a kneeling position and told him to take that one bull turned sideways to them: Put the Nosler behind the shoulder, then pour on the solids. It was then that the hunter noticed that the PH was backing him up on this bull buffalo with an 8X German binocular instead of his customary 470 Nitro Express double rifle.

The PH just shrugged and said, “You should be able to handle this all right by yourself.”

Taking a breath, the hunter hit the buffalo in the shoulder with the Nosler and staggered him. The bull turned to face them and the client put two deep penetrating solids into the heaving chest, aiming right below the chin, and the buffalo collapsed. As the hunter reloaded, the second fine bull remained where he was, confused and belligerent, and the PH urged the hunter to take him, too: “Oh my yes, him, too.”

This bull turned also after the first Nosler slammed into his shoulder, and lifted his head toward them, his scenting nose held high. Looking into a wounded Cape buffalo’s discomfortingly intelligent eyes takes you to depths few other animals seem to possess, depths made more profound by the knowledge that this animal is one very much capable of ending your life. That is a time when you have to be particularly mindful of what you are doing out there in Africa and make your shots count—especially when your PH, already suspect because of the way he talks English and the fact he wears short pants, who is backing you up now on dangerous game with an 8X German binocular, and especially when he leans over and whispers, “Look: He’s going to come for us.”

Another careful breath and the hunter placed two more bullets into the bull’s chest beneath his raised chin, just the way he had on the first one, except this bull did not go down. That left the hunter with one round in his rifle, and as he was about to squeeze it off he mused about whether there would be any time left afterward for him either to reload or make a run for it. Now, though, there was this enraged buffalo who had to be gotten onto the ground somehow, and all the hunter could be concerned about was holding his rifle steady until the sear broke and the cartridge fired and the bullet sped toward the bull—but just before the rifle fired its last round the buffalo lurched forward and fell with a bellow, stretching his black muzzle out in the dirt. Then he was silent.

Standing slowly, the hunter and the PH moved toward the two downed buffalo (the rest of the small herd now galloping off), to find them both dead. Only then in the dwindling light did they see that one of the first bull’s horns, the horn that had been turned away from them when the client first shot, had been broken off in recent combat and a splintered stump was all that remained. He had been a majestic bull at one time, but at least the second bull’s horns were perfect, matched sweeps of polished black horn, almost 50 inches across the spread. And there, both men stooping to squint at it, glittered a burnished half-inch steel ball bearing buried in the horn boss covering the bull’s head like a conquistador’s casco.

The ball bearing had served as a musketball fired from an ancient muzzleloader. Whoever the native hunter was who fired it, he must have had an overpowering lust for buffalo meat, and for buffalo hunting. What became of him after he shot and failed to kill with his quixotic weapon at much-too-close range was probably best not speculated upon.

When I first heard that story I was a boy of 10. It was told by a gentleman of my acquaintance (a man who taught me how to hunt then, and with whom I hunted until he grew too old to hunt, then died), who had experienced it on a safari to then-still-Tanganyika half a century ago. Like the best hunting tales, it was twice told after that, and told more. Unlike other tales it never grew tedious with the tellings, at least for me, only aging gracefully. Every time I heard the gentleman’s excitement in telling it, as if it were the first telling and he had been transported back to those Tanganyikan plains, and saw the massive head on the wall with the steel ball shining in the horn, it explained something to me of why a person could get daffy about hunting Cape buffalo. Its power as a legend was such that it sent me off to East Africa to hunt buffalo myself when I was an age to.

Black, sparsely haired, 1,500, perhaps 1,800 pounds in weight, some five foot at the shoulder, smart and mean as the lash, and with a set of immense but elegant ebony horns that sweep down, then up and a little back, like something drawn in three-dimensions with a French curve, to points sharp enough to kill a black-maned lion with one hooked blow—horns known to span 60 inches across the outside spread—the African Cape buffalo is, along with the Indian gaur and the wild Asian water buffalo, one of the three great wild cattle of the world. Of these, the water buffalo has largely disappeared into domestication—with a few animals transplanted to Australia and South America having gone feral—and the gaur is confined to a significant extent to subcontinental national parks and preserves. The Cape buffalo alone among these has little or no truck with men, other than of the most existential kind. Making it the last native wild cattle that can truly be hunted.

With his ferocious temper, treacherous intellect, and stern indifference to the shocking power of all but the most outlandishly large-caliber rifles, the Cape buffalo is routinely touted as the most dangerous member of the African Big Five (which also includes the lion, leopard, black rhino, and elephant). Whether or not he is all that depends, as does almost everything under the sun, on what you mean. He is certainly not as sure to charge as a rhino, or as swift as the predatory cats; and in the words of a late well-known sporting journalist to me, “nobody ever got wounded by an elephant.” But the buff is fleet enough; and when he makes up his mind to charge, especially when injured, there is no animal more obdurately bent on finishing a fight. In open flat country, he may present no serious threat to a hunter sufficiently armed, but you so seldom encounter him on baseball-diamond-like surroundings rather more often he’ll be in some swampy thicket or dense forest where he is a clever enough lad to go to cover, and fierce enough to come out of it when it is to his advantage.

The best measure of the Cape buffalo’s rank as a big-game animal may simply be the kind of esteem professional hunters hold him in. It is a curious fact of the sporting life that big, tall, strapping red-faced chaps who earn their livelihoods trailing dangerous game, all come in time to be downright maudlin about which animals they feel right about hunting. Most, therefore, first lose their taste for hunting the big cats, so that while they will usually do their best to get a client his one and only lion, their hearts will not entirely be in it: The predatory cats in their appetites for meat and sleep and sex are simply too close to us for absolute comfort. Then there is the rhino, the hulking, agile, dumb, blind, sad, funny, savage, magnificent Pleistocene rhino, that was run to the brink of the Big Jump we term extinction, only to be pulled back all too near to plummeting over. To hunt a black rhino lawfully today is a quarter-million-dollar proposition, involving diplomatic negotiations and something like an Act of Congress, and it seems questionable how truly wild and fair such a hunt might be, though none of that makes the black rhino any less unpredictable or hazardous.

Of the Big Five, then, that leaves only the elephant and the Cape buffalo to feel at all right, in the long run, about hunting; and to my knowledge, hardly any real professional hunter, unless he has lost interest in hunting altogether, ever totally loses his taste for giving chase to these two. There is no easy way to hunt elephant or Cape buffalo. For either of them you must be able to walk for miles on end, know how to read animal sign well, and be prepared to kill an animal who can just as readily kill you without batting a stereoptic eye (it only adds to the disquieting mien of the Cape buffalo that its eyes look mostly forward, so much like a carnivore’s)—and this makes elephant and buffalo the two greatest challenges for taking good trophy animals, and the two most satisfying. Something about hunting them will get into a hunter’s blood and stay. To offer one further bit of testimony on behalf of the buff, consider the widely known piece of jungle lore that the favorite sport of elephants is chasing herds of Cape buffalo round and round the bush, and the buff ’s position as one of the world’s great big-game animals seems secure.

Which is why I wanted to hunt buff, and went to do so in the southwestern corner of Kenya, north of the Maasai Mara and east of Lake Victoria, in the Chepalungu Forest on top of the Soit Ololol Escarpment above the Great Rift Valley on the northern outskirts of the Serengeti, to arguably the loveliest green spot in all green Maasailand, and one which I dearly hated—to begin with, anyway.

To find buffalo there we put on cheap canvas tennis shoes (because they were the only things that dried overnight) and slog every day into the dim wet forest (filled with butterflies and spitting cobras; birdsong and barking bushbucks; gray waterbucks and giant forest hogs; rhino, elephant, and to be sure, buffalo), parting a wall of limbs and vines and deep-green leaves woven as tight as a Panama hat, through which one could see no more than 10 feet in any direction. On going in, the advice given me by my professional hunter, John Fletcher (who stayed on in Kenya when it all ended [with the closure of big-game hunting in 1977]), was that in the event of my stumbling onto a sleeping buffalo (as well one might) I should try to shoot the animal dead on the spot and ask questions later. It took only a momentary lack of resolve at such a juncture, he assured me, to give a buffalo ample opportunity to spring up and winnow you right down. And that was the root cause of my hating this exquisite African land: It scared the hell out of me, and I hated nothing more than having my imagination overextended by fear.

As we hunted the buffalo, though, a change began to come over me. We had unheard-of luck on cats at the outset of the safari, so that at dawn on my fifth morning of hunting in Africa, while concealed in a blind, I had taken a very fine leopard as he came to feed on hanging bait. And then, the evening of the same day, we had incredibly gotten up on an extremely large lion, Simba mkubwa sana in the eager words of the trackers, and I had killed him with my 375, establishing what may very well have been some sort of one-day East African record for cats, with what have been the only two of my life, which we duly celebrated that night. When our hangovers subsided two days later, we moved off from that more southern country near Kilimanjaro to the Block 60 hunting area above the Rift, assuming we took quickly from the forest there a good buffalo (a bull with a spread over 40 inches wide ideally 45 or better, with 50 inches a life’s ambition—along with a full, tightly fitted, wide boss), then move on again to the greater-kudu country we had, until the luck with cats, not hoped to have time to reach.

Instead of a good buffalo in short order, though, we had to go into that forest every day for two weeks, first glassing the open country futilely at daybreak, then following tracks back into the cover, trailing the buffalo who had returned to the forest before dawn, their night’s grazing done.

In that forest where lambent light shafted down as if into deep water, we picked our way for two weeks over rotting timber and through mud wallows, unseen animals leaping away from us on all sides, we creeping our way forward until we could hear low grunts, then the sudden flutter of oxpeckers (more euphoniously known as tickbirds) flaring up from the backs of the buffalo they were preening, and then the flutter of alarmed Cape buffalo flaring up as well, snorting, crashing so wildly away (yet also unseen) through the dark forest that the soggy ground quivered and the trees were tossed about as if in a windstorm, the report of wood being splintered by horns able to be heard for hundreds of yards through the timber.

That was the sound a breeding herd of cows, calves, and young bulls made as they fled; but other times there would be the flutter of oxpeckers and no crashing afterward, only a silence the booming of my heart seemed to fill; and we knew we were onto a herd of bulls, wise old animals who were at that moment slipping carefully away from us, moving off with inbred stealth, or maybe stealthily circling back to trample us into the dirt? For much of those two weeks, then, I saw things in that forest through a glaze of fear as ornate as the rose window in a medieval French cathedral.

I discovered, however, that you can tolerate fear roaring like a freight train through your head and clamping like a limpet to your heart for just so long; and sometime during those two weeks I ceased to be utterly terrified by the black forms in the bush, and instead grew to be excited by them, by the chance of encountering them, by the possibility that my life was actually on the line in there. My heart still boomed, but for a far different reason.

What was going on in that forest, I saw, was a highly charged game of skill: You played it wrong, you might be killed; you played it just right, you got to do it again. Nothing more than that. But when something like that gets into your blood, the rest of life comes to lack an ingredient you never knew, before, that it was supposed to have. I believe it got into mine one evening when we chased a breeding herd in and out of the forest for hours, jumping it and driving it ahead of us, trying to get a good look at one of the bulls in it. Finally, we circled ahead of the buffalo into a clearing of chest-high grass where they had to cross in front of us. We hunkered down and watched as they came out. The bull appeared at last, but he was only a young seed bull, big-bodied but not good in the horns yet. As we watched him pass by, a tremendous cow buffalo, the herd matriarch, walked out, maybe 60 yards from us, and halted. Then she turned and stared directly our way.

If she feels her calf or her herd is threatened, the cow buffalo is probably as deadly an animal as there is; and at that moment I found myself thinking that was just the most wonderful piece of knowledge in the world to have. It meant she might charge, and, may God forgive me, I wanted her to. Very much.

“All right,” John Fletcher whispered, carrying his William G. Evans 500 Nitro Express—with two 578-grain bullets in it and two more cartridges, like a pair of Montecristos, held not like cigars, between his finger, but together in his left palm under the fore-end so they would not separate if he had to jam them in an instant into the broken breech of his double rifle carrying it across his body like a laborer’s shovel, “All right,” he whispered, “we’ll stand now, and she’ll run off. Or she’ll charge us.” Nothing more than that.

We stood, John Fletcher, I, and the trackers behind us, and the buffalo cow did not twitch. We saw her thinking, or at least watching with care, weighing the odds, her nostrils flaring. John Fletcher and I brought our rifles up at the same instant without a word and took aim; as soon as she started forward, I knew I was going to put a 375 into the center of her chest, exactly where my crosshairs were, and if she kept coming, as a charging buffalo always had the intention of doing, I would put in another; but I would not run. As the seconds passed, I felt more and more that, for perhaps one of the few times in my life (a life flawed and warped in so many ways, from when the wood was green), I was behaving correctly, naturally, no fear clouding my vision. To know absolutely that you are capable of standing your ground is a sparkling sensation (but then, I was young). Then the cow snorted and spun away from us, following the herd, her calculations having come up on the debit side. I took my finger off the trigger, then, and carefully reset the safety. And all the trackers came up and clapped me on the back, smiling their nervous African smiles, as if to say, “You did well.” I was glad we hadn’t had to kill the cow after all.

When, at first light on our 14th day of buffalo hunting, we reached the edge of a small dewy field, though, and spotted three good bulls feeding 100 yards away and I got my first chance to kill a Cape buffalo, I did not kill him at all well. Though he was the smallest-bodied buffalo of the three, old and almost hairless, his horns swept out nearly 45 inches, much farther than the other two’s, and when I fired—low, near his heart, but not near enough—he began to trot in a slow circle as the two younger bulls came past us at an oblique angle, just visible in the edge of my scope. I shot him again and again, anywhere, and again, and Fletcher fired the right barrel of his 500, and at last the buffalo went down and I had to finish him on the ground. There was still, I had to admit, after the bull lay dead and all my ammunition was gone, enough fear left in me to prevent my behaving completely correctly.

We went on hunting Cape buffalo after that right up to my last day on safari, John Fletcher looking for an even better trophy for me, and me looking to make up for the first kill, hoping there was still time. On the last morning of hunting we flushed a bushbuck, and I had only the briefest second to make the fastest running shot I have ever tried and took the sturdy little antelope through the heart as he stretched into full flight. Suddenly I was very anxious about having another try at buffalo before leaving Africa.

We found the herd that evening when John and I and my photographer friend Bill Cullen were out alone, the trackers back helping break camp. The buffalo had been drifting in and out of the forest all that gray, highlands afternoon with us behind them, following their tracks—a bull’s cloven print, sizable as a relish tray, standing out from all the others. It seemed that we had lost the herd for good, though, until a small boy, no older than four or five, wearing a rough cotton toga and carrying a smooth stick, appeared startlingly out of the bush before us and asked in the Maasai language if we would like to kill a buffalo.

A little child led us along a forest trail to the edge of the trees, where he pointed across an open glade to the bull. The Cape buffalo bull, his tight boss doming high above his head, stood in the herd of 10 or 15 other animals in the nearing dark, only a few yards from heavy cover, in which in no more than half-a-dozen running steps he could be completely concealed. John Fletcher, for one, was something more than uncomfortably aware of this. He remembered too well how I had killed my first bull, and though he’d said nothing, he knew how much the buffalo had spooked me. If I wounded this bull, now, and he made it into the forest with the light going, and the second rule they give you for dangerous game being that you follow all wounded animals in . . . well. . .

Fletcher looked at me sharply. There was no denying it was a good bull, and the trackers and camp staff wanted some more meat to take home, and there was still a little light, and—and oh, bloody hell!

We knelt at the edge of the trees, and Fletcher whispered to me, “Relax, now. Keep cool. Take your time. Are you ready? Are you all right?” I cut my eyes toward him, then back to the buffalo. I was, at that moment, as all right as I was ever going to get. This was where it counted; this was what it was all about; this was exactly what I’d come here for. It was in my blood now, only Fletcher might not know that. So, I told him.

“Where,” I heard myself whisper, easing the 375’s safety off so it didn’t make a click, “do you, want me to shoot him?”

John Fletcher–now dead and buried in Nanyuki–stared at me even harder then, but this time he whispered only, “There, in the shoulder.”

You can see where a Cape buffalo’s shoulder socket bulges under his hide, and a bullet entering his body there will travel through into his spine where it dips down from his humped back to become his neck. That was where I laid my crosshairs, and when the 270-grain Nosler hit him there it broke his shoulder, then shattered his spine. And the bull was down, his muzzle stretched out along the short grass, bellowing his death song (what the professionals call “music” when they hear it coming from a wounded bull laid up in cover). The rest of the herd wheeled on us then, their eyes clear and wide and most uncattlelike, the smell of the bull’s blood in their nostrils. I finished the bull with one more round to the neck; and the herd was gone, vanishing as quickly as that bull could have vanished had my nerve not held and I had not behaved correctly.

That last night in camp, while the African staff jerked long strips of buffalo meat over the campfire to carry back to their wives and children, John Fletcher, Bill Cullen, and I sat in the dining tent and ate hot oxtail soup and slices of steaming boiled buffalo tongue and drank too much champagne and brandy, and laughed too much, too. We finished breaking camp at dawn the next morning and returned to Nairobi.

Perhaps I have gone on with this story at too great a length already, but I wish I could go on even further to tell you all the other Cape buffalo stories I know (maybe I’ll put them in a book someday; perhaps I have), such as how when you awoke in the middle of the night and stepped outside your canvas tent, you might make out, just there on that little rise at the edge of camp, the silhouettes of feeding buffalo against the cold stars as your urine steamed into the grass. Or the two bulls who came out of the timber with their horns locked, fighting with the crashing force of the crazed brutes that they were at that instant. Or how one of the many herds we chased out of the forest and across the green country led us into a majestic cloudburst, and the storm wind swirled around so that our scent was swept in front of the 50 or 60 funeral-black animals and turned them back on us, and as they started forward I asked John what we did now, and he said lightly, “Actually, we might try shooting down the lead buffalo and climbing onto its back.”

There are other stories without buffalo: How I saw a she-leopard in a tall tree battle a fish eagle over a dead impala. Or how when you killed an animal the sky was a clean delft bowl tipped over you and empty of birds out to the farthest horizon, but how in one minute a dozen naked-headed vultures were circling lazily overhead, sprung from nowhere, waiting to come down to create bare white bones in the tall grass. Or how we could be crossing country in the hunting car at 40 miles an hour and one of the trackers in the back drummed on the cab roof, and when we stopped he leapt down and unerringly wove his way 200 yards out into the scrub, and when we caught up to him he would be pointing placidly at a bush where only then did we see the still-wet newborn gazelle curled underneath it in its nest, staring unblinking at us, the tracker seeming to have sensed its burgeoning life waiting out there.

But the story I wish for most is the one in which I am back in those African highlands I grew to love, hunting the Cape buffalo I grew to love too, probably still scared, but only enough to make me sense my true heart nesting inside the cage of my ribs, beating, telling me, over and over, of what I am capable.

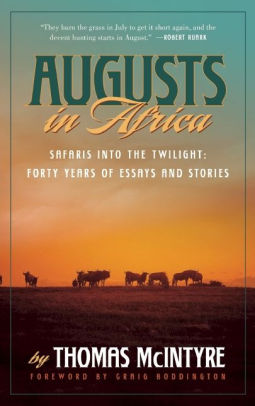

From Thomas McIntyre’s latest book, Augusts in Africa: Safaris into the Twilight: Forty Years of Essays and Stories, published by Skyhorse Publishing and available from Amazon and Barnes & Noble online. Tom is at work on a new book about African buffalo, and will be hunting them again in Burkina Faso next year.