By the summer of 1872, literally thousands of buffalo hunters had converged on the Great Plains. They had (or would soon earn) names like Buffalo Bill Comstock, Buffalo Bill Cody, Cross Eyed Joe, Apache Bill, Buffalo Curley, Wyatt Earp, Pat Garrett, Tom Nixon, Limpy Jim Smith, Buckshot Roberts, Squirrel Eye Emery, Mr. Hickey, Prairie Dog Dave, and California Joe. As their names suggest, these fellows were not stay-at-home-dad types. They were Confederate soldiers escaping the shame of Reconstruction. They were Union soldiers escaping the boredom of victory. They were orphans. They were wanted alive for fraud here, wanted dead for murder there. They were men like Wild Bill Hickok, who killed a man after an argument about who could kill whom the fastest. They were men like Lonesome Charley Reynolds, who turned to buffalo hunting after he shot the arm off an army officer at Fort McPherson, Georgia. They were men like Crooked Nose Jack McCall, who was hanged for shooting Wild Bill Hickok in the back of the head.

Different hide hunters worked in different ways, but the ones with a head for business started their own outfits. An outfit was usually managed by the shooter. He’d hire a couple of skinners and a camp tender. A six man outfit might depart civilization with two or three ox drawn carts loaded with barrels of coffee, salt, sugar, flour, camp equipment, skinning equipment, and bullet making materials: five twenty-five-pound kegs of Du Pont gunpowder, eight hundred pounds of lead, hundreds of brass casings, and thousands of cartridge primers.

Heading into dangerous country, a hide-hunting outfit might travel with another outfit or two for safety’s sake. While the wagons headed toward a general area where buffalo herds were expected to be hanging around, the shooters would cut broad circles on horseback scouting for buffalo sign. The scouts might be gone from the wagons for several days at a time, returning to their rendezvous point only when they found a herd or cut a good trail. When they did find buffalo, they didn’t storm into the herd with their guns ablaze. They were more calculated than that. First they’d check the lay of the land and find a good campsite, preferably in a deep gully or canyon where they were hidden from Indians. They also needed a water source and plenty of buffalo chips or wood for cooking fuel. With the camp set up and everything ready, the shooter would get some sleep and then ride out early in the morning. They liked .44, .45, and .50 caliber rifles manufactured by Sharps and Springfield, and they carried hundreds of cartridges. Most shooters liked cartridge belts that they could wear around their waist; such a belt held about forty two rounds. A shooter might wear two, or else put his ammo into a bandolier worn across his chest.

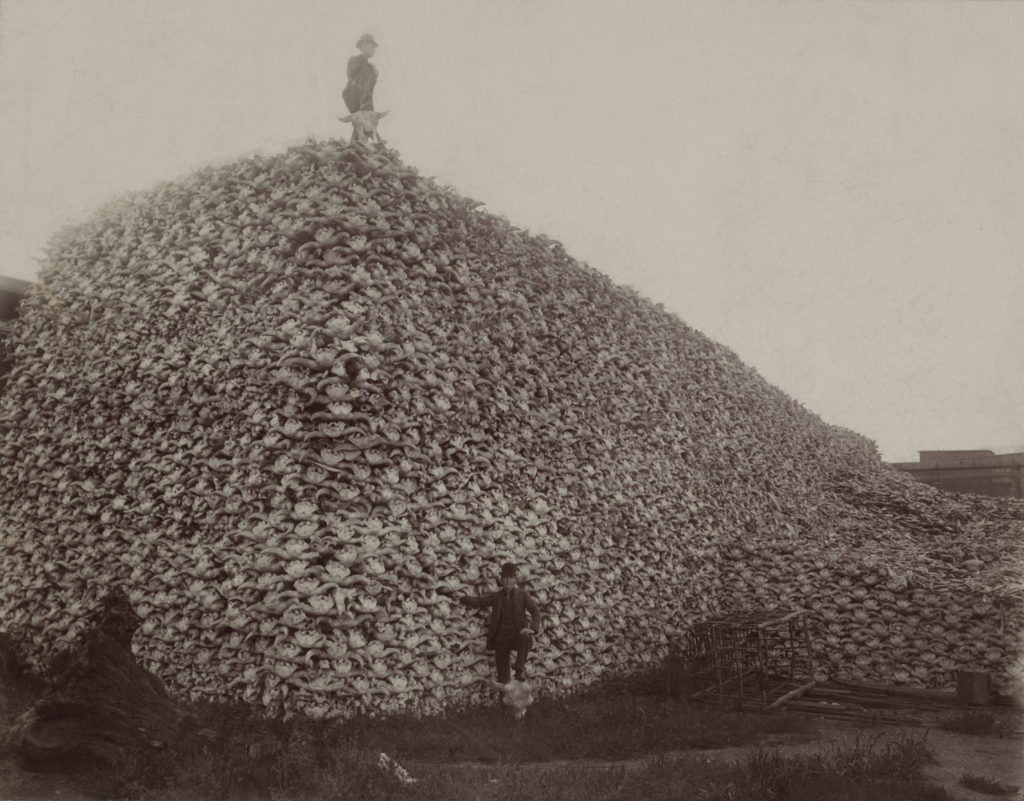

Remains of a hide hunter slaughter somewhere in Canada

A shooter would tether or hobble his horse somewhere close to the herd but well out of sight and downwind. Then he’d study the herd. Which way was the wind blowing? Were they feeding or sleeping? Holding still or walking? Preferably, the buffalo would be still. If there were thousands of the animals, the shooter would select a particular band off to the side of the main bunch. A group of about fifty was a good number. Then he’d use creek beds or sagebrush clumps or stands of cottonwoods to stalk within a couple hundred yards. If he got too close, he’d risk spooking the herd. If he was too far off, he’d risk making bad hits and wounding buffalo.

He’d get his gear all set and ready before he started shooting. He needed a solid rest, someplace to steady the barrel of his gun. He might use a wadded up jacket, crossed sticks stuck into the ground, mounds of packed snow, or mounds of buffalo chips. He’d take off his ammo belt and lay it next to him. Then he would try to determine the herd’s leader. Usually an older cow, the leader might be out in front of the herd and setting the pace of movement. That’s the one he wanted to hit first. If the buffalo were bedded down, the shooter might not know who the leader was. If that was the case, he’d pick a buffalo on the outer, distant edge of the herd.

The shooter would send his bullet through the target’s lungs, which were called “lights.” A lung hit buffalo usually wouldn’t run but would just take a few steps before sinking to its haunches and tipping over. It would kick for a second and then be still. The fallen buffalo’s herd mates could respond in a number of ways: the buffalo might walk up and smell the blood pouring from the animal’s nose; they might act very aggressively toward the downed animal and gore it; they might ignore it; they might slowly walk away; or they might take off in a wild stampede. The shooter was hoping for any reaction but the latter. The goal was to have the herd milling about in complete confusion—no idea where to go, no idea where the danger was coming from. As soon as one of the buffalo showed any initiative toward leaving, the shooter would put a bullet in its lungs. If the buffalo seemed to want to travel in a particular direction, the shooter would drop an animal or two in its path and change its mind. If a buffalo ran, the shooter would try to knock it down in a hurry. If he fired more than a round or two a minute, his rifle barrel would get too hot. J. Wright Mooar cooled his barrel by pissing on it. Snow came in handy for this purpose.

When a herd started moving away from a shooter, it was said to be “adrift.” The shooter would follow along, going from downed body to downed body so he could use the carcasses as rifle rests and hiding places. He had to be careful, because half dead or stunned buffalo might get up and charge him. Sometimes he’d prop his gun on a downed buffalo, and it would be breathing or twitching too much for him to get a solid rest. The buffalo might lift its head and stare at him, wild eyed.

There are documented reports of shooters killing one hundred or two hundred buffalo within an hour or two, but thirty or forty was usually considered a good day’s shooting. A shooter didn’t want to go too far over that number, because he was limited by how many hides his skinners could remove. Left overnight, buffalo bloated too much, and the hides got tight and hard to pull off. Or wolves ripped them up. Or the carcasses froze.

In really good hunting, skinners might make upwards of $20 a day. They usually got twenty five or thirty cents per hide, though skinners from Mexico would do it for twenty cents. Skinners followed along in the shooter’s path with a wagon. Some skinners drove a big steel rod through the buffalo’s head, anchoring it to the ground. Then they’d make the skinning cuts and pull the hide free with a draft team. Other skinners didn’t like this method, because it left too much meat on the hide. They’d just skin the animal slice by slice with a knife. In skinning females, the entire skin was removed except for the forehead and nose. The hide on the head of a bull was too tough to skin, so they left the whole thing from the ears forward. The historian Mari Sandoz said that these bull buffalo, when covered in white fat, looked at a distance like maggots with black heads.

The hides had to be pegged out to dry, meat side up and fur side down. In wet weather, the skinner flip flopped the hides back and forth until dry. The skinners would either do the hide staking right where the buffalo fell or else haul the hides back to camp and do it there. If the ground was soft, they’d use wooden pegs. If the ground was frozen, they might use rocks, or just stretch the hide as best as they could and hope that the bunchgrasses and cacti held it in place. A skinner might carve his initials in the subcutaneous tissue. When the hides were dried out, usually after a week or so, they’d stack them into piles that were eight feet high. They’d cut leather cords from fresh hides and then run the cords through holes cut in the bottom and top hides, so they could cinch the stack down tight. Now the hides were ready to be hauled to a railroad depot. After a few months out, or “a season,” a hunting outfit could have upwards of four thousand or five thousand hides. Prices varied. When the hides were really flooding in, they sometimes dropped down to $1.00 or less. Toward the end of the hide hunting era, when the only buffalo left were in Montana, hunters were getting $3.50for cows, $2.50 for bulls, $1.50for yearlings, and seventy five cents for calves. Maybe a thousandth of that meat went to market. Beyond the occasional load of brined tongues (twenty five cents apiece) or smoked hams (three cents a pound) it simply wasn’t profitable to handle meat. If it had been, the hunters would have gladly buried the railroad tracks in the stuff.

In 2005, Steven Rinella won a lottery permit to hunt for a wild buffalo, or American bison, in the Alaskan wilderness. Despite the odds—there’s only a 2 percent chance of drawing the permit, and fewer than 20 percent of those hunters are successful—Rinella managed to kill a buffalo on a snow-covered mountainside and then raft the meat back to civilization while being trailed by grizzly bears and suffering from hypothermia.

American Buffalo is a narrative tale of Rinella’s hunt. But beyond that, it is the story of the many ways in which the buffalo has shaped our national identity. Rinella takes us across the continent in search of the buffalo’s past, present, and future: to the Bering Land Bridge, where scientists search for buffalo bones amid artifacts of the New World’s earliest human inhabitants; to buffalo jumps where Native Americans once ran buffalo over cliffs by the thousands; to the Detroit Carbon works, a “bone charcoal” plant that made fortunes in the late 1800s by turning millions of tons of buffalo bones into bone meal, black dye, and fine china; and even to an abattoir turned fashion mecca in Manhattan’s Meatpacking District, where a depressed buffalo named Black Diamond met his fate after serving as the model for the American nickel.

Available online for purchase: