As hunters we face a brave new world each and every year as we ward off various threats to our lifestyle and the wildlife we love to pursue. Habitat loss due to urban sprawl and the ever increasing demands on our natural resources, environmentalists and anti-hunters lobbying against us at the local, regional and National level and the near viral expansion of technology and its effect on our youth and their interest in the natural world around them all pose a significant threat to the future of hunting.

Yet I would argue these threats are not our primary concern. No, it is the “cannibalism” within our own ranks that will be our ruin. The infighting between hunters around the world over topics such as “trophy” hunting, long range hunting, and high fence hunting to name a few and their ethical and conservation implications will be the demise of hunting and hunting opportunities if we do not take action on a personal level first. It is our personal responsibility to educate ourselves on the facts and science behind some of these contentious topics and apply reason and logic to the discussion before forming strong opinions. Emotions have no place at the table, and it is only emotions that will allow us to be divided and conquered.

As the saying goes, one twig breaks easily but a bundle of twigs remains strong. But for the bundle itself to remain strong each individual twig must have the inherent strength to resist cracking. It is knowledge that makes us strong individually and it is knowledge and facts that will win the day against the threats to our hunting lifestyle. I say this, not from a position of superiority but rather from having been in the very position myself where my strongly (aka emotionally) held opinions and beliefs about certain hunting and conservation related topics were not sufficiently backed by facts or conservation science. When David Marsh’s wolf story came across my email inbox it catalyzed my decision to use our last issue of 2014 to discuss some of the more contentious topics within our community and highlight some important facts as it relates to conservation. Our Pro Insight column will open your eyes to the importance of maintaining “trophy” records and our Blazing Trail interview with the founder of the Rocky Mountain Goat Alliance will make you think about the difference between a legal “meat” harvest and a responsible one. As new hunters join our ranks, especially those that come from a non-hunting family or background it is our responsibility to ensure they are well educated on the facts involved with being a modern hunter and conservationist.

My personal story is an especially interesting journey and in my opinion highlights just how real the risk of “cannibalism” within the modern hunting community truly is. So let’s start there.

I grew up in the Ottawa Valley, in Eastern Ontario, Canada on a hundred acre farm in a rural setting that I am beyond grateful my parents chose to raise their family in. We lived within a ten minute drive of my mother’s four brothers, all of them farmers. Through the influence of my father and my uncles, fishing, hunting and the outdoors were an absolutely central part of my upbringing. We fished year round, rifle and bow hunted whitetails in the fall, often using hounds during rifle season. We hunted wolves and dabbled in trapping in the winters and honed our shooting skills on groundhogs (prairie dogs for you Westerners) in the summer. There was always a gun in a truck and fishing, wildlife, cattle and the environment were topics extensively discussed and debated at dinners and family events. In short, I was raised an outdoorsman. Wolves in particular were a constant topic as my uncles were beef and cash crop farmers and I can remember looking with awe at the hide of the 100 lb timber wolf one of my uncles had proudly hung in his family room. As a young teen I was handed an old but meticulously maintained, deadly accurate and smooth cycling .30-30 and told that before I could shoot any of the scoped rifles I needed to learn to shoot the open sighted lever gun first. And learn I did. It was this rifle I carried for years in the highlands and hardwoods of my home Province and it was this rifle I carried through knee and waist deep snow, following wolf tracks and “pushing bush” in an attempt to drive the wolves to my cousins and uncles waiting in the fields with their flat shooting, hard hitting .22-250s, .25-06s and .280s. We didn’t hate the wolves. It was simply the natural thing to do. Wolves fed on our livestock so we hunted them, plain and simple.

One particular event stands out in my memory. It was Christmas Day and we were at one of my uncles’ for Christmas brunch. We were a big extended family, so the holidays usually entailed twenty to thirty aunts, uncles, cousins and grandparents all gathered together to celebrate the occasion and this was no different. I couldn’t have been more than fifteen at the time. Lunch had just finished and the snow that had been falling all morning had finally let up. My grandmother was at the kitchen sink, doing some dishes when she looked out the window and remarked “Oh look, a wolf”. A lone timberwolf was standing at the far end of the field that backed the property, roughly 400 yards away. Without hesitation, every male in the house jumped to his feet and ran for the door. As the trucks and snowmobiles parked outside warmed up, a plan was formulated and the hunt was on.

Yes, even Christmas Day took a back seat to hunting, especially when it came to wolves.

Fast forward to the end of high school and my athletic commitments started to conflict with my fall and winter hunting opportunities and by the time I arrived at university, hunting had taken a back seat to numerous other priorities. I attended university far from home and could rarely afford the time and expense to go home for a weekend of hunting and there always seemed to be exams scheduled in the middle of deer season. This was the height of my estrangement from the outdoors lifestyle I was raised to love. After university I bounced from one large city to another in Canada due to my work commitments but never felt at home. The outdoorsman that had been lying dormant within me was stirring and these large cities were becoming increasingly difficult for me to tolerate. The stories I’d read as a young boy of the wild and mountainous West began to percolate and eventually boiled to the surface and at the drop of a hat I moved to British Columbia, the Province I will almost certainly call home for the remainder of my life. A Province where I have more hunting and fishing opportunities than any human being could fulfill in a lifetime and where spending time in the mountains is a central way of life. One I have embraced thoroughly since moving here years ago.

So why is all this important? Because my story, one of a rurally raised individual that finds themselves living a more urban existence due to the realities of pursuing post-secondary education and a career is not uncommon in the 21st century. And because, of all people that should remain open minded about all methods of hunting and all reasons for hunting I lost touch. As my love for hunting was rekindled I found myself justifying hunting to my friends in the city by referring to myself as a “meat hunter” and looking down my nose at the “trophy hunters” wantonly killing for the sheer egotism of a head on their wall. I defended my fellow meat hunters to my non-hunting friends but willingly threw the bear and mountain lion hunters under the bus, especially those that used hounds to tree the bears or cats so they could “walk up to them” and shoot them out of the tree. How sporting was that after all? And you surely couldn’t eat a black bear or a mountain lion could you? I ran my mouth off about never killing anything I wasn’t going to eat and was aghast at stories of grizzly hunters taking the hide off a big boar and leaving it to “rot” in the wilderness. Not for one second thinking about the fact that that carcass would be well utilized by the natural world in no more than seventy-two hours from that bear being killed. I was so horribly uneducated and self-righteous that if I could go back in time I would kick my own ass and spit on the unconscious body as I walked away.

Ignorant statements like my own from years ago should sound familiar. Within the hunting community, one does not need to look far or spend too much time online before running into one hunter throwing another hunter under the bus. Whether its trophy hunting, high fence hunting, baiting, long range hunting, or killing only what you can eat the hunting community is filled with strong opinions, opinions that in many cases are not backed by facts, science or logic. And this is especially true on matters related to conservation and what exactly, the practical application of conservation entails. I am not proposing that we all need to get along. But I am suggesting that given the numerous threats to our way of life we cannot afford to “eat our own”.

We must present a front of solidarity. And to do so we must educate ourselves and our fellow hunters on the facts related to any one of these contentious topics. So with this in mind, I’d like to tackle a hotly debated subject both within our own ranks and within the battle for public opinion, and that’s the matter of killing only what you eat. This was a topic I personally felt very strongly about for years before opening my eyes, taking ownership of my beliefs and critically analyzing the facts behind being a “meat hunter”.

If you consider yourself a “meat hunter” and especially if you are not exactly in favour of predator hunting or “trophy” hunting where the meat is a secondary priority to the age and maturity of the animal taken, ask yourself this simple question. Do you truly need the meat? Remove your taste preferences, remove your “moral” beliefs, and remove the organic argument from the equation and apply reason and logic. Would you go hungry if you didn’t hunt for your meat? And is that meat removed from the environment better used by you and your family as opposed to the predators and scavengers that might feed on that animal if it were to die of old age? When most of us can drive no more than fifteen minutes in any direction and buy meat with no more effort than pulling out our wallets, the answer is unequivocally no. So let’s be honest with ourselves, unless you live in the far reaches of the wilder Provinces or States and live a subsistence way of life you want to hunt and you want that incredibly healthy and luscious game meat in your freezer. But you do not need it. And there is absolutely nothing wrong with wanting the meat, but it does not wash the blood off your conscience nor does it make you a more “ethical” hunter than the “trophy hunter”.

Let’s dig even deeper. As a meat hunter, do you openly commit to shooting the first legal animal you see and happily kill the first small buck, raghorn bull or spike-fork moose that crosses your path? The meat is that much more tender and succulent after all isn’t it? Now ask yourself, what effect does the harvesting of this young male have on the population in your area? And on the balance of conservation science, is that a more responsible harvest than a mature animal that has spread its genetics and is likely past prime breeding age? Is that tough as boot leather front shoulder meat less “valuable” to you and your family than that of the young bull or buck? I suggest you read Mr. Sprigg’s article on the Science Behind Keeping Records before using the term “trophy hunter” negatively again.

And what about the hide you left in the woods? Is that deer, elk or moose hide less valuable than the meat you labored over to bone and pack out? Can gloves, mitts, belts, slings, not be made from the hide? Can the hair from an elk not be used to tie flies? How is leaving the hide behind but removing all edible portions of meat any different than the grizzly bear hunter or wolf hunter taking the hide and leaving the carcass? From the standpoint of pure logic there is no difference. And is that carcass not better utilized by the many scavengers of the wild? Is it not typical human egocentrism to think we can make better use of the meat than the ecosystem it comes from?

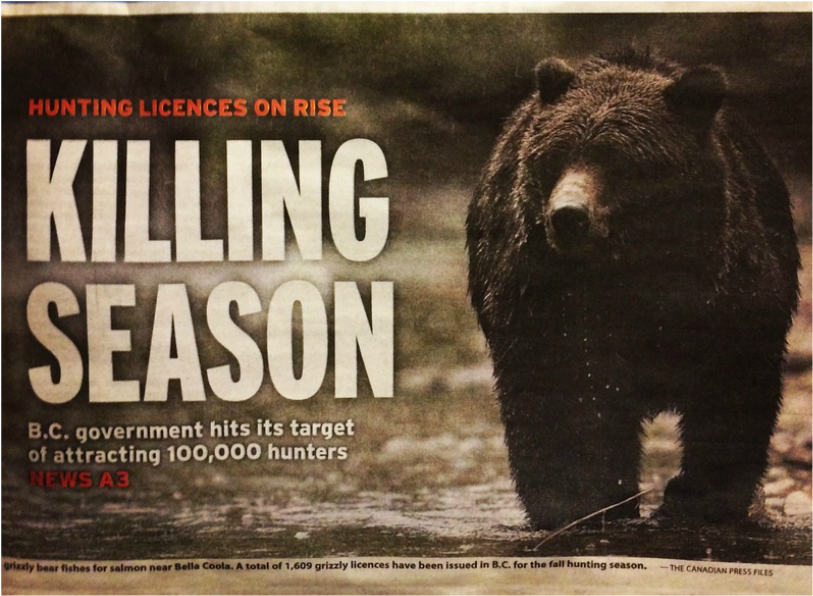

The predator hunting subject in particular is one I held strong but illogical opinions on until I educated myself on the facts. It is without question one of the most pivotal issues within our own hunting community and in our ongoing battle against the anti-hunters. The grizzly hunt, here in BC, and the wolf hunt in the Rocky Mountain West are two topics truly on the front lines of the fight for conservation versus preservation, public opinion and the way of life we all love. The entire debate hinges on the concept of “meat hunting” as opposed to the otherwise “senseless” killing of these predators for “nothing more than their hides”. As hunters, it is our responsibility if not our obligation to face the facts. In today’s world a hide is no less personally “valuable” than a freezer full of game meat. Is that perfectly cooked elk roast served over the holidays any less of a “trophy” than the bear rug stretched out in front of the fireplace? The rug that kids and grandkids will be amazed by and learn about wild places and wildlife from? No, the term “trophy” is entirely within the eye of the beholder and if we lose the battle for the “trophy hunt” we will eventually lose the war for the very way of life we all love.

I implore each and every one of you to make a pledge to our hunting future and take action. Spend the time this off-season to research the facts and science behind any one of these contentious topics but in particular “trophy” hunting and predator hunting, especially as it relates to our great bears and the wolves proliferating across the Canadian and American West. I am not suggesting you need to become a wolf or bear hunter. But don’t look down upon your fellow hunter because their definition of a “trophy” and their contribution to conservation is different from yours. And don’t sit idly by at parties or dinners when non-hunters embrace the game you serve but condemn those that hunt the “endangered” predators “simply for the hides”. In the battle for public opinion it is the non-hunters and the fence sitters that we need to educate. But we must educate ourselves first.

In a world driven by information knowledge is power. And in our modern society, one that is increasingly losing touch with the ways of Nature and where our children think meat comes from the grocery store our solidarity as hunters, conservationists and outdoorsmen and women is the only insurance we have to guarantee the future of hunting and our wildlife for generations to come.

Adam Janke

Editor in Chief